A ceramic bowl discovered off the coast of Egypt may contain the world’s first reference to Christ.

The so-called ‘Jesus Cup’ was unearthed in 2008 by a team led by French marine archaeologist Franck Goddio during an excavation of Alexandria’s ancient great harbor.

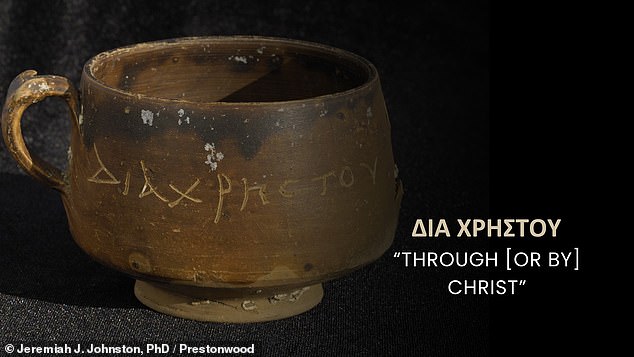

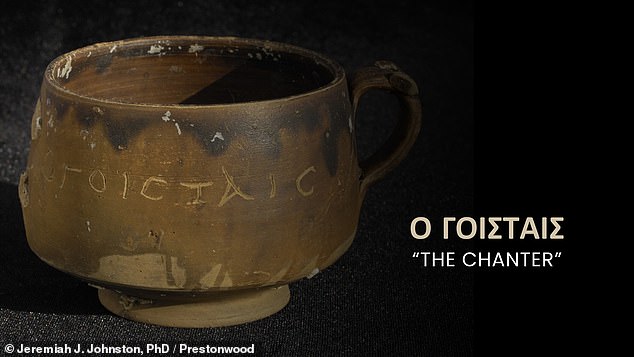

Remarkably well preserved, the bowl is missing only a handle and bears a Greek inscription: DIA CHRSTOU O GOISTAIS, translated as ‘Through Christ the chanter.’

Dr Jeremiah Johnston, a New Testament scholar, explained on a recent Trinity Broadcasting Network (TBN) segment that the artifact dates to the first century AD, the era when Jesus was crucified.

‘Jesus’ reputation was that he was a healer, miracle worker, and exorcist,’ Johnston said. ‘This Jesus Cup gives evidence to that legacy.’

Goddio suggested the inscription may have been intended to legitimize soothsaying rituals. The bowl closely resembles those depicted on early Egyptian statuettes, showing fortune-telling ceremonies.

Ancient manuals describe how practitioners poured oil into water and entered ecstatic trances, seeking visions of mystical beings who could answer questions about the future.

Invoking Christ, already recognized as a powerful wonder-worker, may have lent authority to the ritual.

The ceramic artifact is believed to be the first reference to Christ. Dr Jerimiah Johnston shared the story about the discovery while recently speaking on the Trinity Broadcasting Network, where he said it dates to the first century AD

‘The disciples came to Jesus and said, ‘Teacher, people are using your name to cast out demons. Should we stop them?’ Jesus said, ‘No, a house divided against itself can’t,’ Dr. Johnston told TBN.

‘Jesus, through his own short ministry of just three years, others are invoking his name because it had so much power.’

Goddio and his team found the cup at an ancient Egyptian site that included the now-submerged island of Antirhodos, where Cleopatra’s palace may have been located.

Alexandria in the first century was a cosmopolitan hub where paganism, Judaism, and Christianity overlapped.

Magical practices incorporated figures from multiple traditions, and the name of Christ sometimes appeared in both pagan and Christian magical texts.

‘It is very probable that in Alexandria they were aware of the existence of Jesus,’ Goddio said, noting Christ’s associated legendary miracles, such as transforming water into wine, multiplying loaves of bread, conducting miraculous health cures, and the story of the resurrection itself.

However, not all experts are certain it translates into the earliest reference to Christ.

Bert Smith, a professor of classical archaeology and art at Oxford University, proposed that the engraving may have been a dedication or gift from a person named ‘Chrestos,’ who belonged to a possible religious group called the Ogoistais.

Archaeologists who found it off the coast of Egypt suggested it was used by a fortuneteller, hoping Christ’s name would make them more powerful

Klaus Hallof, director of the Institute of Greek Inscriptions at the Berlin-Brandenburg Academy, added that if Smith’s interpretation is correct, ‘Ogoistais’ could be linked to cults that worshipped early Greek and Egyptian deities such as Hermes, Athena, and Isis.

Hallof also noted that historians from the era of the bowl, including Strabo and Pausanias, mention a god called ‘Osogo’ or ‘Ogoa,’ suggesting the inscription could reference a variation of this deity.

It’s even possible, he said, that the bowl refers to both Jesus Christ and Osogo.

Scholar Steve Singleton argued that chrêstos simply means ‘good’ or ‘kind,’ translating the inscription as ‘[Given] through kindness for the magicians.’

György Németh of Eötvös Loránd University proposes a practical explanation: the bowl may have been used for preparing ointments, with Chrêstos or DIACHRISTOS referring to an anointing salve, not the biblical figure.

If the inscription truly refers to Jesus Christ, it could represent the oldest material evidence of his existence outside Christian scripture, dating to the first century AD.

This would push back the historical footprint of Jesus in Egypt, suggesting awareness of his life and miracles extended far beyond Judea within decades of his ministry.

Confirming this reading would challenge historians to reconsider the timeline and geography of early Christian influence.

It might prompt re-evaluation of Alexandria’s role as a center of religious exchange and innovation, bridging pagan, Jewish and Christian traditions