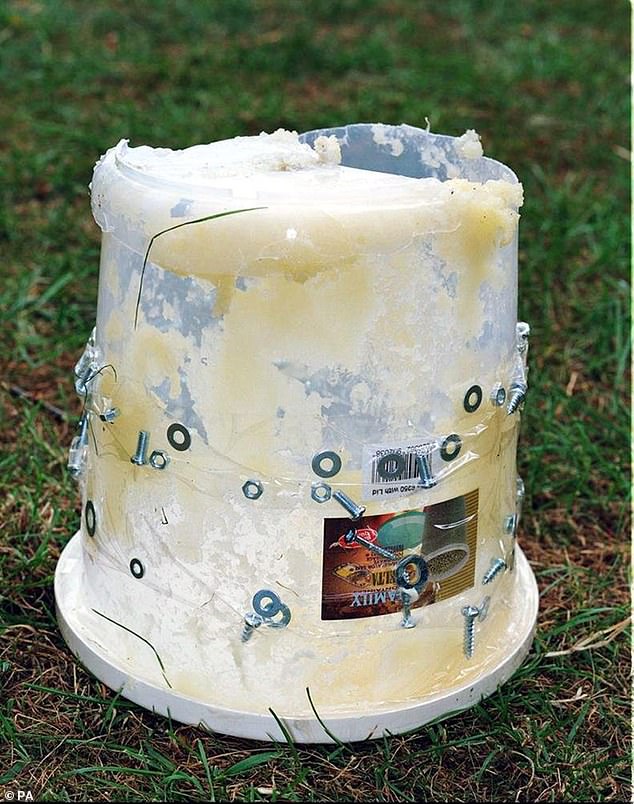

Park-keeper Jackie Whitcombe was picking up litter in Little Wormwood Scrubs Park, West London when he came across a plastic container in the bushes.

Bending down, he grabbed it in his gloved hand and suddenly spotted dozens of screws, washers, nuts and bolts taped around the outside. He knew instantly what it was – a makeshift bomb designed to kill and maim.

‘I slowly put it down and briskly walked away,’ he recalls. An explosives officer was quickly on the scene. He cut into the container, emptying the contents onto an anti-static sheet. It was wet, sticky, bubbling gloop identical to the explosive mix found at four bomb scenes in London – at three Tube stations and on a double-decker bus – just two days earlier.

Those home-made bombs had fizzled out, with no repetition, thank goodness, of the terrible scenes earlier that month of July 2005 when four explosions on Underground trains and a bus, triggered by militant al-Qaeda suicide bombers, had killed 52 Londoners and injured hundreds of others.

This latest wave of attacks, through good fortune, had failed, causing no loss of life. But the public were on high alert, aware that somewhere out there were at least four would-be bombers set on mass murder.

Tests confirmed that the substance in the container was hydrogen peroxide, a harmless disinfectant or hair dye in small quantities but which, in large concentrations, could be boiled up into a home-made explosive. There were five kilos of it, along with a detonator packed with another home-made explosive. It had all the elements of a viable device, designed to replicate the carnage wreaked two weeks before.

The capital was in a state of near-panic as the spectre of further suicide bombs frayed its inhabitants’ nerves. Hundreds of citizens called in suspect devices or people behaving suspiciously.

Firefighters and cops with bomb-sniffing dogs sealed off city blocks and evacuated rows of restaurants, pubs and offices – all to a soundtrack of wailing sirens and pounding police helicopters.

The rear of the bus destroyed by an explosion at Tavistock Square near Euston Station, London

At New Scotland Yard, senior officers were convinced that the failed suicide bombers were holed up and perfecting their techniques for a series of follow-up attacks.

A massive, unprecedented manhunt was launched to find them before they could strike again, directed from an intelligence hub where investigators were urgently sifting through information from the counter-terrorism hotline, witness statements and forensics.

The news of the bomb discovery in the Wormwood Scrubs Park increased everyone’s anxiety.

‘Now we potentially had five failed suicide bombers on the run,’ recalled Assistant Commissioner Andy Hayman, the officer in overall charge of counter-terrorism. ‘Then you start to speculate if there is going to be a sixth or a seventh? Are there devices planted in other parts of London?’

After the previous day’s appeal for information, more than 500 calls from the public came into Scotland Yard about the four suicide bombers. Among them was one from William (surname withheld, at his request) who’d seen the smudgy mugshots of the suspects on TV and recognised them.

He was the caretaker of Curtis House, a run-down council block of flats on Ladderswood Way, New Southgate, in north London, dubbed ‘The Little Block of Horrors’ by locals because of its broken lifts, leaking roofs and graffiti. In recent months, he had become friendly with Yasin Omar, a man in his 20s who lived at No 58 on the 9th floor.

William was a Christian, Yassin a Muslim, and they had a running joke about which one was going to convert the other first. Just a few weeks earlier, William had loaned Yasin his wheelbarrow. ‘As he was a friend I didn’t even ask what he needed it for.’ But now he had his suspicions.

William called the police hotline.

A distraught commuter is consoled after the series of explosions

Next morning, he observed that in the communal refuse area, dumped around the bins, were numerous bags full of plastic containers. Inside were dozens of empty bottles of hair dye. He called the hotline again, and then a third time. On this occasion he received a call back. Officers were on their way to Curtis House.

In the bins, they discovered more than 200 empty containers of hydrogen peroxide, as well as other components for bomb-making. Here, then, was evidence of the terrorist cell’s bomb factory, high up in a tall building, with at least some of the terrorists likely inside and armed for a small war.

The challenge for the police was how to approach the flat, because if any of the failed bombers were inside, any hint of police activity might provoke them to go out in a violent blaze of glory.

A year earlier, in Madrid, Islamic terrorists who had killed 200 commuters in bomb attacks on trains had blown themselves up when cornered, killing a police officer.

The police proceeded with caution. If failed suicide bombers were in there, it would almost certainly lead to an armed confrontation. If the flat was empty, there was always the risk of booby traps.

Doug McKenna, the officer in charge of the investigation, had a firearms team on standby but decided to watch and listen for 24 hours before taking any action. Covert surveillance was placed outside the flat; technicians also monitored any movement or conversations inside.

Among the firearms unit on standby was an inspector we will call ‘Tony’. He was 26 years in the job but remembers being uncomfortably aware that, up until this point, the criminals he and his colleagues came up against had wanted to escape, or at least they’d wanted to live. Something altogether new now confronted them at Curtis House – people who didn’t care if they died.

‘In the back of your mind,’ says Tony, ‘there’s a reality that you might not be coming home from this job.’

Armed police prepare to raid flats where the terrorist suspects were believed to be hiding

The 24 hours passed, and in the early hours of Monday, July 25, with nothing being seen or heard from the suspected bomb factory, officers discreetly organised the evacuation of the eighth, ninth and tenth floors of Curtis House.

Neighbours were shocked to learn that the friendly guys at No 58 were implicated in the previous week’s attacks, as the men had often helped elderly neighbours with their shopping and played football with local kids.

They recalled how the suspects never entered the lift if it was already occupied. And, come to think of it, they always seemed to be carrying unspecified objects in plain plastic bags…

At 3am, armed police began the painstaking trudge up 18 sets of steps, each carrying about 20 kilos of gear. They reached the ninth floor and edged towards the front door of No 58. Tony felt his chest tighten as the officers at the front took a battering ram to the door. BANG! They all feared a massive flash and blast. BANG! The door flew open. ‘We looked around,’ says Tony. ‘We’re all still here,’ They charged in, but no one was home. The birds had flown.

The suspects had, though, definitely been there. Tests revealed the fingerprints and DNA of two of them, Yasin Omar and Muktar Said Ibrahim, as well as traces of home-made explosives. Notes in Arabic in Ibrahim’s handwriting revealed his determination to die a martyr.

On another sheet was some rudimentary arithmetic which showed that he had slightly miscalculated the ratio of ingredients for the explosive devices, which is why they had fizzled out without causing damage. The failed bombers had been one multiplication step away from killing and maiming countless innocent people.

SHORTLY after the Curtis House disappointment, a member of the public called the counter-terrorism hotline with information that Yasin Omar was staying at an address on Heybarnes Road in Small Heath, west Birmingham.

An armed police team was quickly outside, bundling out of the van and running to the back door of the flat. Two officers forced the door open. ‘Police! Police!’ they shouted. The rest flooded in. A young detective constable, Sean, tossed a stun grenade into the bedroom and followed it in. There was no one there.

Muktar Said Ibrahim and Ramzi Mohammed surrendering to the police following a siege in West London

But elsewhere in the flat he heard screaming. Two officers were yelling at the top of their voices in the bathroom. Sean rushed over and saw Omar standing in the bath with a backpack on, wires hanging from its pockets. He was screaming at the officers, they were screaming back and pointing their Glock 17 pistols at him.

‘I thought he had a bomb on his back,’ says Sean. ‘For a split second I remember thinking, “This is it. He’s going to set that off and I’m done for”.’ But the other officers grabbed Omar’s hands to stop him being able to detonate anything. Omar struggled hard and Sean reached for his Taser.

‘I fired into his neck, to avoid the backpack as much as possible and incapacitate him.’

Omar slumped backwards against the wall. Another officer stormed in, wrestled the rucksack from his back and ran through the flat to the back door, where he threw it towards some bushes. A later search revealed it didn’t contain explosives – the hanging wires belonged to phone chargers.

Sean found Omar’s behaviour perplexing, given his lack of munitions. He’d tied the bathroom light cord to the inside door handle so that when the officers pushed the door open, the light clicked on.

Not only was he standing in the bath wearing a rucksack with wires hanging out, he also had a mobile phone in his hand. ‘I think he wanted us to kill him,’ says Sean, ‘suicide by cop.’

Here was a chilling indication of the new enemy they were facing.

THE following day, Thursday July 28, the police had a new lead to follow when evidence came to light linking Oval bombing suspect Ramzi Mohammed with an address at a sprawling Peabody Trust estate in Dalgarno Gardens, Notting Hill. Surveillance officers were sent to the estate.

The discarded device left at Little Wormwood Scrubs, made from screws, washers, nuts and bolts taped around the outside of a plastic container

An undercover tech expert approached the fourth-floor flat of K Block dressed as a council worker, complete with clipboard, high-vis singlet and hard hat and carrying a device. His cover story was that he was checking a reported gas leak, but in fact the device was a new piece of kit that could detect if a certain mobile phone was inside the flat.

He stood outside, conscious that on the other side of the door could be an armed and desperate suicide bomber ready to shoot him. After an agonising 120 seconds, his device pinged and he had his confirmation – Ramzi’s phone was indeed inside Flat 14.

The following day, firearms officer Tony led the assault, not expecting much ‘because we’d done so many addresses that week that turned out to be empty’. But this time he was wrong. From the top of a block opposite, officers with powerful telescopic sights had a visual of Ramzi through the window.

Cautiously Tony led his team up the concrete staircase to the fourth-floor walkway. For all they knew, Ramzi had been in there for days constructing bombs and was ready to mount an ambush.

At the top of the stairs, Tony asked an explosives officer what would happen if the suspect detonated a bomb inside the flat. ‘We won’t know much about it, Tony,’ came the reply. Tony and his team had to evacuate K Block before addressing whatever awaited them behind the door to No 14. As anxious residents were led out, Tony received a call from one of his officers clearing the flat next door to No 14: the raid was being covered live on Sky News.

The channel’s camera was pointing directly at the fourth-floor walkway of K Block. ‘Are you sure it’s live?’ asked Tony. The officer leaned out of the front door of flat 13, and waved. ‘Yes, guv, it’s live.’

Tony was appalled that the suspects might be watching the rolling news. ‘If they’d had explosives,’ he says, ‘this would have helped them to cause maximum casualties and the death of our officers.’

Although Sky agreed to put a time delay on their coverage, the presence of cameras unsettled Tony. He felt it exposed him and his team in their most difficult hour.

Ramzi Mohammed running through Oval Underground Station after dumping the remnants of a makeshift bomb

He had been planning to storm No 14 but now he saw how risky that might be. What if it was booby-trapped or the suspects had weapons? He decided the safest option was to somehow force them outside and make the arrests on the balcony.

Negotiators arrived on site, and, using a megaphone, opened a dialogue with the people inside. One reassured Ramzi that he and the others would be safe if they came out stripped to their underwear, hands in the air. Another warned them that the cops were armed and ready to storm in. Neither approach worked. The tense stand-off developed into a siege.

When asked why they wouldn’t come out, a male voice replied: ‘I’m scared. How do I know you won’t shoot me?’ He was clearly referring to the massive police blunder a week earlier in shooting dead a completely innocent Brazilian, Jean Charles de Menezes, mistaken for one of the terrorists.

The stalemate dragged on. For Tony, the longer the suspects remained inside, the more time they would have to prepare and deploy whatever weapons they might have and the greater the threat. He needed to bring this to an end.

He knew the layout of the flat and that Ramzi and an unidentified friend were in the sitting room at the back. For them to come out on to the balcony at the front, they’d need to walk into the hallway, then past the kitchen and bathroom. If they had a device, he was confident his marksmen could take them out before they reached the front door – provided there was no front door.

They needed to remove the front door, but it couldn’t just be battered down by conventional rams, as doing so would expose the officers. Fortunately, SAS personnel were on hand with explosives, and they agreed to take down the front door. Shortly after midday, a deafening bang rang through Dalgarno Gardens, shattering the door.

As the raid was no longer covert, Sky News switched to live.

On the other side of the cordon, TV crews could hear the police instructions – ‘Mohammed, take your clothes off.’ Through their megaphone, police kept asking, ‘Is there a reason that you shouldn’t leave the flat?’ But still the men refused to come out.

The blasts on the bus and three underground trains killed 52 people

Officers approached the gaping hole where the front door had been and fired a CS gas canister towards the rear of the hallway. No one emerged. Eight minutes later, they fired in another. Then from the rear of the block they lobbed two plastic capsules through the sitting-room window.

There was a delay, then suddenly the rifle officer in front of K Block reported movement in the hallway of No 14. Everyone froze. Were they coming out, stripped down with their hands in the air, as instructed? Tony and his team peered into that hallway, poised and ready.

Broadcast live on rolling news, viewers first of all saw a bare arm, then a face peering out, red and puffy. The police recognised the distinctive features of Muktar Said Ibrahim, who emerged naked to the waist, arms aloft, tears and snot running down his face.

Ramzi Mohammed, the terrorist they’d come for, walked out immediately afterwards, stripped down and looking resigned to his fate. These were the last two suicide bombers on the loose in London, and they were surrendering in front of the media.

Tony felt exultant. ‘We were showing the world that these two terrorists were no longer a threat to London and the public,’ he says.

Detective Superintendent Jon Boutcher, who had been running the raid from the control room at Scotland Yard, recalls: ‘Days before, these two men had sought to blow up innocent people in London. To get them under control was an incredibly good feeling.’

All four of the would-be suicide bombers – Muktar Said Ibrahim, Yasin Hassan Omar, Ramzi Mohammed and Hussain Osman – were found guilty of conspiracy to murder and each was sentenced to life imprisonment with a minimum of 40 years.

A fifth man, Manfo Asiedu, who’d dumped the makeshift bomb in Little Wormwood Scrubs Park but backed out of detonating it, was jailed for 33 years.

- Adapted from Three Weeks In July by Adam Wishart & James Nally (Mudlark, £25), to be published June 19. © Adam Wishart and James Nally 2025. To order a copy for £22.50 (offer valid to 21/06/25; UK P&P free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.