This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

“Kamala is for they/them, President Trump is for you.” Thus went the kicker of what many believe was the most consequential ad in the 2024 American presidential campaign. Meanwhile, in the UK, the North Hertfordshire Museum has decided to use the pronouns “she/her” when referring to the early-third-century Roman emperor Elagabalus, during whose reign a coin was minted that the museum owns.

One may wonder what Dame Mary Beard thinks of this. As she wrote in the Spectator World late last year, “Elagabalus” is her usual response to the common question, “Which emperor is Donald Trump most like?”

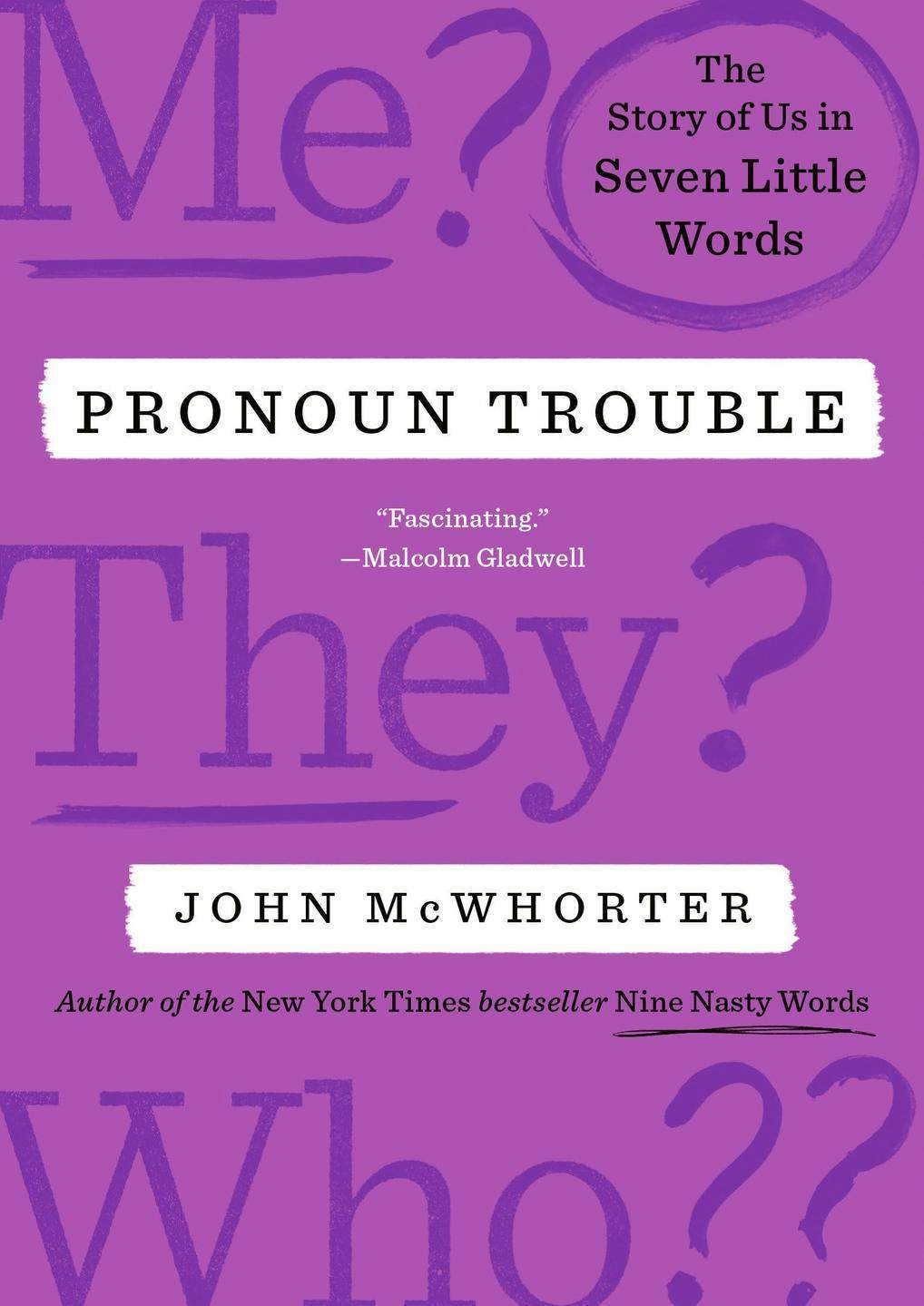

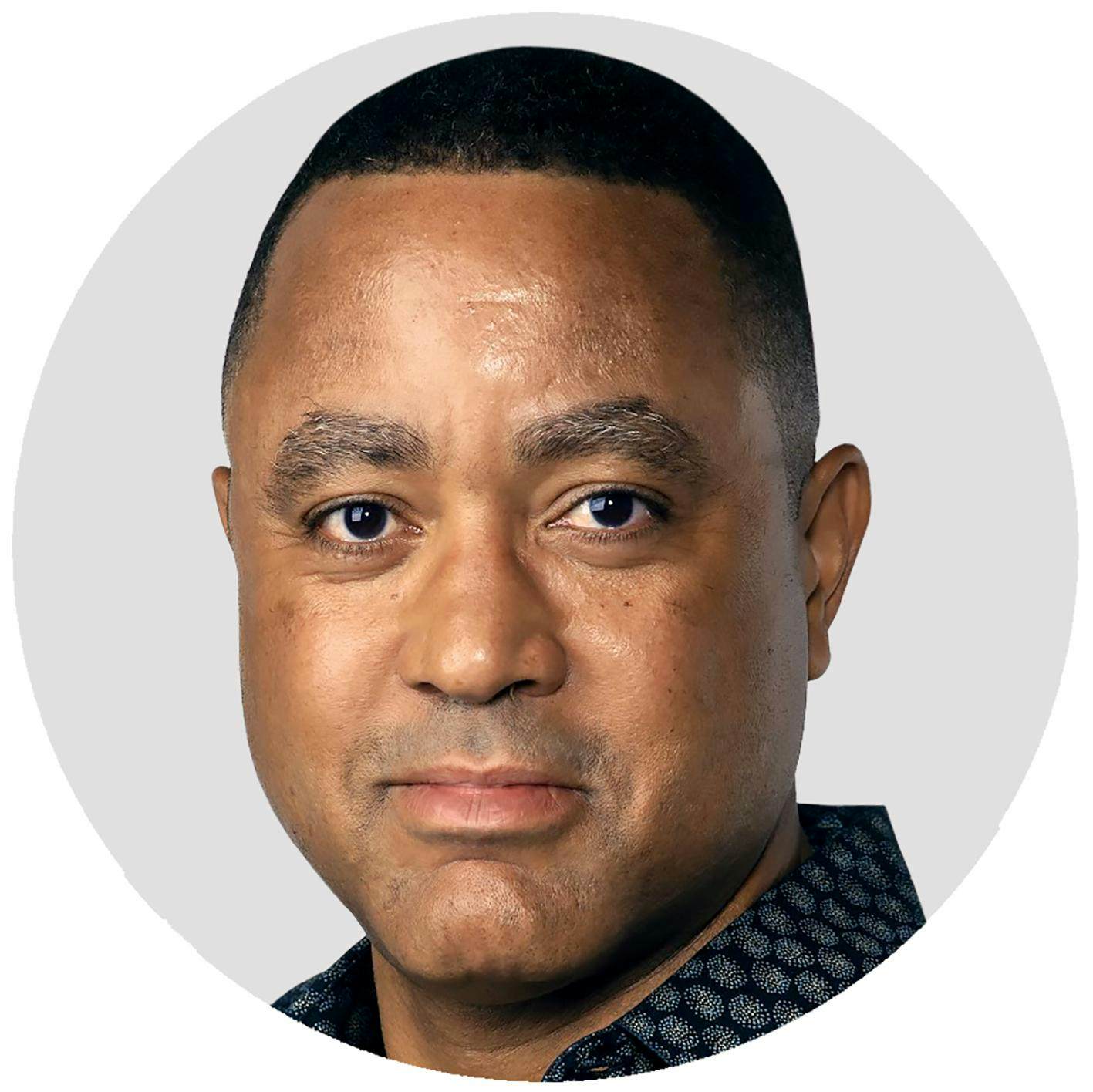

In a world that is grappling, often painfully, with issues of gender and identity, it is not surprising that America’s most prominent public linguist, John McWhorter, decided the time was right for Pronoun Trouble: The Story of Us in Seven Little Words.

McWhorter tells us that the title of his brief book comes from the 1952 Looney Tunes cartoon “Rabbit Seasoning”, but — as I am not the first to point out — he is surely also nodding to Judith Butler’s hugely influential 1990 monograph Gender Trouble. Butler, whose pronouns have since become “they/them”, famously argues for the performative nature of gender — the most important noun in Butler’s world and yet one whose precise meaning they (?) has (?) great difficulty defining themself (??), as Alex Byrne explains in his wonderful 2024 book Trouble with Gender.

But pronouns are far too interesting to be left to trans activists on either side, and McWhorter, who mentions three different Looney Tunes along the way, wisely leaves “they” and its friends for the last chapter. (He misses a trick in saying nothing about “themself”.)

For over 150 pages beforehand he writes, with characteristic if sometimes mystifying humour, about what makes other pronouns such as “I”, “you” and “we” fascinating as well, the last of which he believes to be like a couple of balls of apricot brandy-flavoured sorbet. “[F]ierce, captious little things”, personal pronouns typically pass without notice — unlike unusual sweets — because they are ubiquitous in everyday speech: amongst the most common words in the language.

Readers will learn from McWhorter about the odd “aren’t I” (we don’t say “I aren’t”); the difference between “y’all” and “all y’all” in Southern American English; and the gender-neutral pronoun “yo” that has emerged in the Black English of young people in Baltimore. They will also encounter his suggestion, which I like very much, that “uklun” — the equivalent of the plural pronoun “us” in Pitkern, the English-Tahitian creole that arose on Pitcairn and Norfolk Islands after the mutiny on the Bounty — is a corruption of a dual form like “unker”, which is how speakers of Middle English expressed specifically “the two of ours”.

Not everything is smooth sailing, to be sure. Some will be vexed by McWhorter’s defence of phrases like “Him and me went to the store” (I’m too conservative to like this myself, though a strong case is presented); offended by what he says about the pronominal use of “a bitch” and “a nigga” (as in “a bitch is broke”, meaning “not only I but many people like me are broke”); or baffled by his suggestion that Sancerre is not a variety of Sauvignon Blanc (but as he himself puts it, “I’m no wine connoisseur”).

Furthermore, experts will not all immediately rush to accept McWhorter’s accounts of how exactly the pronouns “she” and “they” came over the past millennium to look and sound as they do or — particularly interesting to me — to believe the putative prehistories he sketches here and there of what have been called the language’s “Devonian rocks” on account of pronouns’ apparent antiquity and resistance to morphological analysis.

What about the meaning of “they”? Many will be displeased that McWhorter is “a great fan of the new usage of they”: that is to say, of “they” not in its longstanding but still contested employment as a generic singular (e.g. “no one has to go if they don’t want to”) but rather with reference to a specific person.

Indeed, “[i]f it were decreed that from now on singular they were to be used with –s [e.g. they wants],” McWhorter tells us, “I would get used to it and even kind of enjoy it like a new cocktail. I doubt I am alone.” He is not alone, but when we next get together, he’s having that cocktail and I’m sticking to Sancerre.