A Government-issued digital identity card could be required by every adult in Britain under a ‘dystopian’ plan set to be announced by the Prime Minister.

The ‘BritCard’ could be used to prove a person has the right to work in this country, and even to access public services.

The idea of a mandatory identification system has long been advocated by Labour as a way to tackle illegal migration.

But the proposal is fiercely opposed by civil rights campaigners, who warn it will erode civil liberties and turn the UK into a ‘papers please’ society.

Meanwhile, polls show a majority of the public do not trust ministers to keep their personal data safe from cyber-criminals.

Detailed proposals for what has been dubbed a ‘Brit Card’ could be announced by Sir Keir Starmer as early as tomorrow.

The Prime Minister will speak at the Global Progress Action Summit in London alongside Australian prime minister Anthony Albanese and Canadian prime minister Mark Carney.

These plans will then be subject to a consultation and are expected to require legislation. The UK is one of the few countries in Europe without an ID system.

How would Sir Keir Starmer‘s new ID cards work?

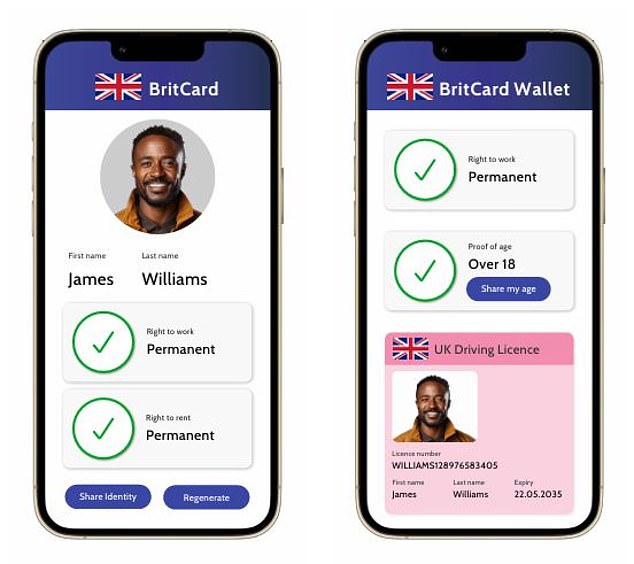

It is likely to be a smartphone app, rather than a physical card.

A previous UK scheme – ultimately abandoned – relied on a digital photograph which can be used to confirm someone’s identity by measuring the precise distance between their facial features.

It is possible that any new scheme would require holders to also provide other biometric details – such as fingerprints.

Details on the card could be cross-referenced against a central database, holding tens of millions of records for the British population.

Because it is likely to be smartphone-based the project could also use the facial ID features widely used on phone handsets, in personal banking apps, for example.

However, the Government is thought to be some distance away from coming up with detailed proposals.

Detailed plans for what has been dubbed a ‘BritCard’ could be announced by the Prime Minister as early as tomorrow. Pictured: Mock-ups of what the cards could look like

Hasn’t this all been tried before?

Yes. Tony Blair’s Labour government passed legislation for a national ID card scheme in 2006.

Detailed plans were published when Jacqui Smith was home secretary, although by that time ministers had abandoned the idea of making the cards compulsory.

The scheme actually went into operation in 2009, when Alan Johnson was running the Home Office, with credit card-style cards which each carried a microchip.

The Passport Service issued the cards a £30 a pop to volunteers from October 2009.

But after the following year’s general election the entire scheme was ditched by then home secretary Theresa May.

By then, £257million had been spent on the proposals.

Then Labour home secretary Jacqui Smith holds a sample national identity card before the launch of the earlier scheme in 2008

Labour’s Alan Johnson was home secretary when the previous scheme went live, offering the cards to volunteers for £30

Couldn’t Labour’s new cards just be forged like any other document?

Its resilience would depending on the type of checks that are built into the system.

A digital ID card would, theoretically, be harder to forge than a traditional document.

For example, a live cross-referencing with a central computer database of names and photos would be almost impossible to cheat – because the holder of the digital ‘card’ would have to look like the photo held on the database.

Less rigorous checks, however, would have the potential to be hoaxed.

It is simply too early to assess how successful Labour’s project could be.

Will I get fined if I refuse to have a national ID card?

The Labour government’s previous attempt at introducing a compulsory scheme did not include fines for failing to register.

This was mainly because the roll-out never reached a compulsory stage.

The legislation behind the scheme did, however, introduce a series of penalties for failing to update information held on you, such as home address or any change of name.

The fines were up to £1,000.

There were similar penalties for failing to surrender a card.

It is still unclear how Labour will proceed with the new scheme and how it will propose dealing with refuseniks.

Labour’s previous attempt at introducing a national ID card scheme was in 2009

What is it meant to achieve?

The card could be used to prove someone is who they say they are, and that they have the right to be in Britain.

Labour is interested in the programme in order to crack down on illegal working.

This would theoretically reduce the attraction of Britain to small boat migrants and other illegal immigrants.

It would also make life harder for foreigners who come to Britain legally but then fail to leave, and yet carry on working.

Further uses of the card could be in other situations where people have to prove they have the right to be in Britain – such as the ‘right to rent’ a property.

Where the project would become highly controversial is access to healthcare and social security.

Labour’s last stab at a national identity card was first floated by then home secretary David Blunkett in 2001, when he referred to it as an ‘entitlement card’.

At that stage, it was intended to allow people to prove they had the right to access the NHS or welfare benefits.

But there was opposition from doctors, for instance, who said life-saving treatment could not be denied on the grounds of nationality.

The NHS continues to have huge difficulty clawing back cash from foreign nationals who have come to Britain as ‘health tourists‘.

Mr Starmer is said to have been sceptical of ID cards on civil liberties grounds before coming over to the idea.

What if I don’t have a smartphone?

It is far too early to say how Labour’s scheme would deal with people who do not possess a smartphone.

This group is likely to include a large number of elderly people.

If they, or others, were penalised under the scheme it would risk being dubbed discriminatory.

A solution could be providing an alternative way to access the details normally held on a digital ID card – perhaps using a laptop or desktop computer – when necessary.

How much is it likely to cost the taxpayer?

Billions of pounds.

The IT systems would most likely have to be developed from scratch.

Depending on the specification of the card, it could require a network of centres across the country where members of the public provide their biometrics.

Labour is aiming for a crackdown on illegal working. This would theoretically reduce the attraction of Britain to small boat migrants (pictured: migrants cross the Channel this month)

What are the potential problems?

If the system flops, like the last one, it would be an almighty waste of money.

The technology behind the scheme is likely to be unlike anything the British government has attempted before.

The civil service’s record on handling the roll-out of new IT scheme is abysmal – a slew of projects have run years late and billions of pounds over budget.

So this vast new undertaking would be high-risk, to say the least.

Then there are the huge civil liberties questions posed by a national ID card scheme.

Unlike many other parts of the world, peacetime Britain has never had a ‘papers please’ culture.

Many will feel it is an invasion of their privacy.

Pressure group Big Brother Watch has said the plan suggests Britain is ‘sleepwalking into a dystopian nightmare’.

Then there is the question of data security.

The government has suffered a large number of damaging data leaks and hacks.

If a new database containing everyone’s details was compromised, it would have the potential to be catastrophic.

Do other countries have digital ID cards?

Many countries including Estonia, Spain, Portugal, Germany, India, the UAE and France use digital IDs.

France has repeatedly claimed that the lack of ID cards in the UK acts as a pull factor for Channel migrants, who are able to find work in the black economy.

Shadow justice secretary Robert Jenrick said it won’t ‘make a blind bit of difference to illegal migration’.