Cynically timed for Christmas, celebrity authors have reimagined the classic characters

A few years ago, when the excellent Ben Schott published his equally excellent second Jeeves and Wooster novel, Jeeves and the Leap of Faith, it was, rightly, billed as “an homage to PG Wodehouse”. Writing about it for The Critic, I called it “a combination of the old and new, done with panache and wit”. The most interesting thing about the book was that Schott — best known for his Miscellanies — was not attempting to write a limp pastiche of Wodehouse, but instead took his peerless characters and updated them in a new, often hilarious direction. Schott was not the first author to have attempted to revitalise Plum — Sebastian Faulks did the same with Jeeves and the Wedding Bells, which sacrilegiously ended with both Jeeves and Bertie, the eternal bachelors, married off — but he did so with considerable pizzazz.

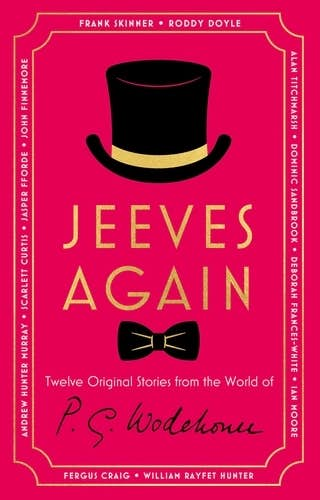

I had hoped that there would be a third Schott-Jeeves novel, but alas it did not come to pass. Instead, the publisher Hutchinson Heinemann has now followed on from similar attempts to update Agatha Christie’s Marple and Poirot characters and has corralled an all-star cast of authors, celebrities and Wodehouse fans to bring back Jeeves and Wooster in a dozen new short stories. It swiftly becomes clear that whoever was in charge of the project seems to have the most eclectic taste in writers imaginable. This will, undoubtedly, be the only compilation of stories that you read this year — probably ever — that has Frank Skinner and Alan Titchmarsh rubbing shoulders, figuratively speaking, with Roddy Doyle and Jasper Fforde. All twelve of them appear to have little in common with each other in any literary way, save the Jeeves and Wooster IP.

Every one of the dozen writers approaches their story — of varying length — with one big idea. In some cases, this is a structurally clever one; Dominic Sandbrook does not attempt to provide a Jeeves and Wooster story, but offers instead a Craig Brown-esque series of fictitious documents and first-hand accounts relating to Wodehouse’s great comic buffoon, the black shorts-sporting Roderick Spode, aka Lord Sidcup. Frank Skinner manages to update the stories to the present day with aplomb, following on from a bizarre incident in which Bertie and Jeeves have been cryogenically frozen for decades, and Roddy Doyle manages an uproarious piece of Oirish surrealism, “Ah Jaysis, Jeeves” in which a Euromillions winner decides that it should befit his new standing in society to hire a gentleman’s gentleman. Enter the most famous butler in literature.

When the stories work, then, they really work. And when they don’t work, they tend either to read like half-finished squibs (such as John Finnemore’s account of fine wine and spirits being disguised as ink in a requisitioned WWII-era Brinkley Court) or alternatively to have perversely misunderstood the point of the Jeeves and Wooster stories. Deborah Frances-White attempts to discern a homoerotic undercurrent in the relationship between the two men in “Mixed Doubles”, something that Wodehouse would neither have anticipated nor, in all likelihood, understood, and the less we say about television gardener Alan Titchmarsh’s woeful “Jeeves and Wooster II”, the better for all concerned.

Yet the central problem with the stories — even the better ones — is that Wodehouse himself remains inimitable. The reason why the original Jeeves and Wooster novels and short stories work so well and remain so entertaining, over a century since they were first created, is that Wodehouse’s remarkable linguistic dexterity and broad range of allusion seems utterly effortless, making the stories as light as one of super-chef Anatole’s soufflés. None of the writers here can manage this degree of effervescent wit, and so, at best, they remain pleasant and amusing reminders of what a marvellous talent Plum was, and at worst there is the taint of the cash-in with a book like this clearly timed for the lucrative Christmas market.

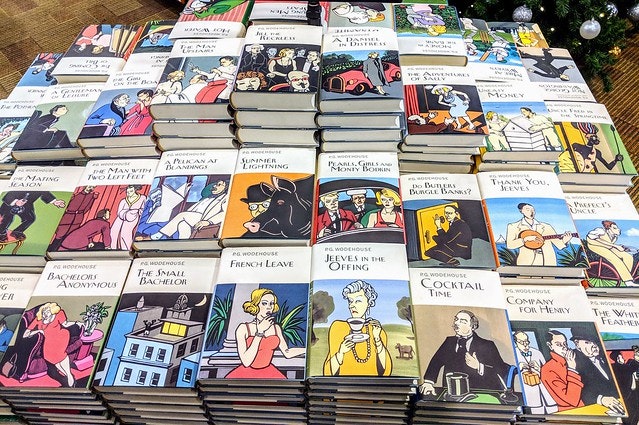

But don’t, for heaven’s sake, give the uncle that you don’t really like Jeeves Again this December because you can’t think of anything better to bestow upon him. Instead, go back to the originals — or, for that matter, the Schott titles, which are head and shoulders above anything here — and give some of the funniest stories ever written to someone who you really care about, instead. That, after all, is a course of action that will leave the recipient decidedly gruntled.