A recent study by Lauren Gilbert of Renaissance Philanthropy makes the case that the “Boriswave” cohort of immigrants are unlikely to be a fiscal drain on the country. By taking data on the earnings of migrants on different visas from this time period, the author constructs a household income figure for each type of visa and dependants. Taking a weighted average across the averages of 3 primary visa categories (skilled worker main applicants, dependants, and humanitarian visas) they conclude the average new migrant who arrived in 2019-2023 made 4 per cent more than average earnings overall. However, the paper’s conclusions rely on some heavy assumptions, statistical errors, and key omissions.

First we must address one of the most important omissions in the paper: it completely ignores the possibility of the migrant gaining Indefinite Leave to Remain, and subsequently citizenship, and thus the automatic entitlements that could be received by the migrant once this is achieved. Karl Williams has done excellent work on this in “Here To Stay?” about migrants gaining ILR, estimating that it could cost the Treasury hundreds of billions of pounds. The OBR has done some rudimentary estimates on the lifecycle of fiscal costs/contributions of migrants but relies on assumptions itself: that the migrant arrives at age 25, and with no dependants. They then estimate the cost/contribution in low/medium/high wage scenarios for these migrants. In practice, we know the age profiles and number of dependants arriving in Britain on these different visas are much different, with many arriving at later ages and with many dependants.

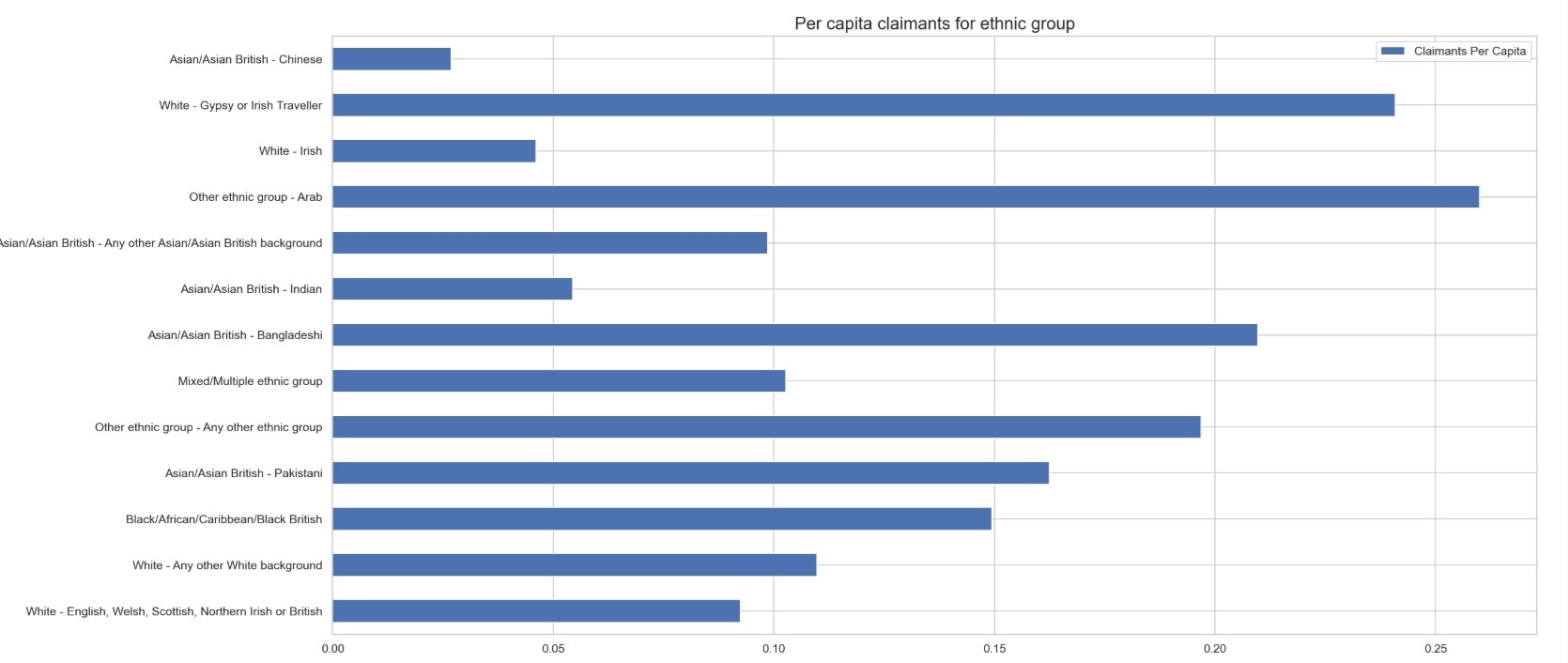

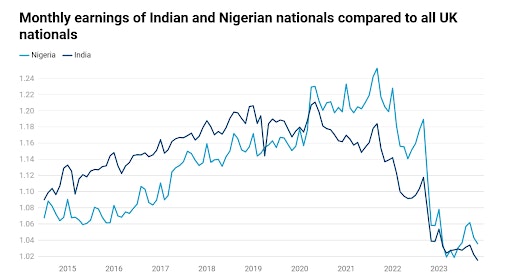

Universal Credit and the State Pension are where the real fiscal time bomb lies. Using recently released data about Universal Credit from the DWP, we see a per-capita breakdown of Universal Credit claimants by ethnic group. A significant proportion of Boriswave migrants come from ethnic groups which are statistically more likely to claim Universal Credit than White British people. Furthermore, for some categories, such as Indians and Nigerians, the recent arrivals have in fact lowered the average wages for those immigrant groups, which Neil O’Brien has pointed out.

ILR will also give the migrants access to the State Pension, provided they have at least 10 qualifying NI years. However, even if they do not, they will be entitled to other benefits such as Pension Credit if their total income falls below a certain level. Given the vast numbers on lower wages in the care sector, we are very likely to see increased demand for these benefits once the Boriswave cohort enters retirement.

There is also the question that even taking the study’s conclusions at face value, a 4 per cent higher average earnings against natives result does not in fact prove that immigrants are not a fiscal drain. The median salary in Britain falls short of actually being a net contributor. Government calculations show that the top 10 per cent of earners (~£72k p/a in 2025) contribute over 60 per cent of income tax receipts, and an Centre for Policy Studies paper in 2012 showed that in order to be a net contributor one needed to be in the top 40 per cent of earners.

Additionally, the paper makes a few statistical fallacies that must be addressed. First and foremost, it builds a “Household Income” by adding the median salaries for main applicants to the median salaries of dependants in that same category. This is an error as you cannot merely add the medians of two independent distributions to achieve, in this case, a household income. One would need the underlying micro-data of individual household compositions to build a clear picture of household income. Likewise, it fails to note that the salary data provided by the Home Office sampled only adult dependants, and did not include children in the study. This will overinflate the numbers as far fewer dependants than the author assumes will be working. Children will be a fiscal cost as they consume services such as doctors, schools, and other public infrastructure. The “bed-blocking” effect is not accounted for at all.

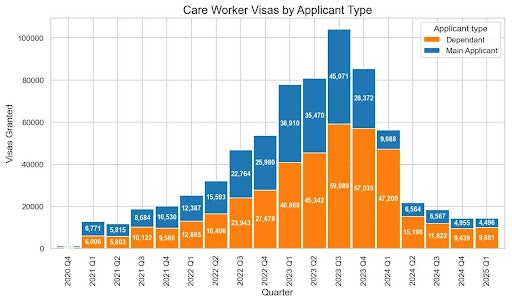

Crucially, the data for earnings ends in Q1 2023. Over half the Health and Care Worker visas granted during the “Boriswave” period were from Q2 2024 onwards. Their salary thresholds were low: £20,960 in 2023 for those “in health and educational roles” or “in shortage occupation roles”. They predominantly came from poor countries such as India, Pakistan, Nigeria, or Zimbabwe. It is difficult to imagine that missing out on nearly 400,000 new entrants in what are typically poorly paid roles would not have an effect on the calculations.

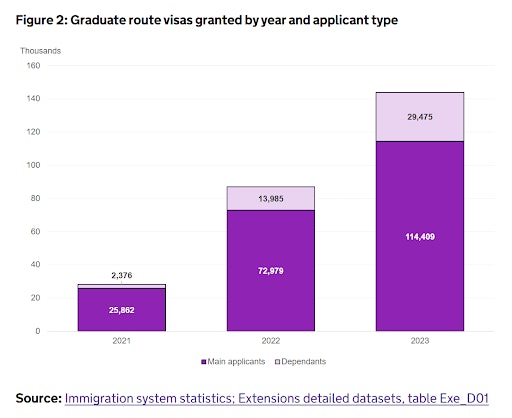

Students are yet again a glaring omission in the study. The Boriswave saw a marked increase in the number of students entering Britain. With the reintroduction of the graduate visa route, many more came and have the right to stay for at least two years after completing their studies. Some, we know, end up disappearing into the system and becoming illegal immigrants (the so-called Deliveroo visa). Millions of people came on this route and will have been eligible for the graduate visa once completing their studies. An undergraduate student in 2019, assuming a 3 year course, would be completing their graduate visa time by Q3 2023. We can see this via the Home Office statistics and reports on this visa route. In 2023 alone, over 100,000 people applied for the graduate visa route after being eligible, with nearly 30,000 dependants in tow. Similarly, a nontrivial number of people will be switching from the study/graduate route to the “skilled worker” route and thus be put on the path to ILR. Ignoring such a substantial proportion of immigrants and their pathways to the state benefits system fundamentally misunderstands a massive element of the debate around immigration.

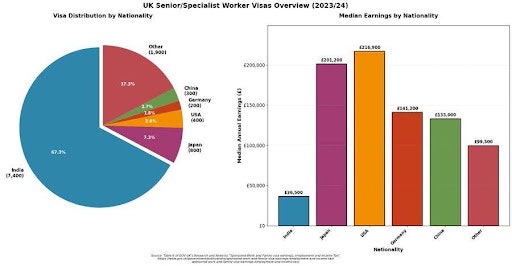

We do well to remember that the calculations obtained are for median earnings to begin with. Over half of people will be earning less than that. Additionally, there are numerous people who “hide in the median”. Over half of those on Senior/Specialist worker visas in 2023/24 were given to Indians, who earn substantially below the median earnings of other nationalities granted the same visas. A sensible immigration policy would instead select for the small number of extremely highly-skilled and highly paid immigrants without filling low-paid or average work with hundreds of thousands of people. It is unnecessary to bring in so many low-paid care workers to justify the small number of highly paid tech workers or executives.

Ultimately, any study on the nature of the fiscal impact of immigration cannot simply be point-in-time to wages but in fact a full life-cycle analysis. The rudimentary OBR modelling does not cut it given the heterogenous composition of migrants in the Boriswave. The author makes a laudable attempt to actually quantify what the impact will be but misses key drivers and statistical facts in making that point. Further study on assessing this impact would be welcome.