The first sign of the 2026 Winter Olympics appears underground.

Above the rain-slicked stone streets, Milan residents step out of city-center cafés, umbrellas popping, seemingly unaware that the final countdown to the Games has begun. But underground, in the signature 2026 Milan Cortina teal blue, is a sign – an actual sign – with two arrows. Turn here for metro lines that travel to the ice skating and hockey arenas.

If the Games have yet to overtake Italy’s fashionable economic hub, then the International Olympic Committee is likely giving itself a pat on the back for achieving one of its goals for these Winter Games.

Why We Wrote This

Rising price tags for a ballooning international sporting event have many would-be Olympic hosts rethinking their bids. The International Olympic Committee is testing a new approach in Italy by using existing venues and multiple cities to shoulder the Games.

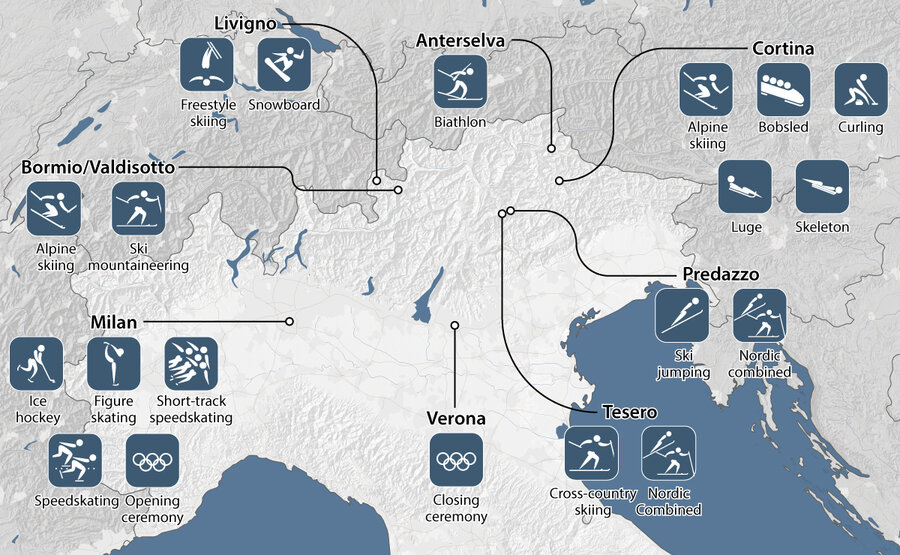

A new era is here. Hosting the Olympics no longer needs to be place-based; it can be dispersed across a country or region. Spanning 22,000 square kilometers (about 8,490 square miles) of northern Italy, crisscrossing the Italian Alps from the Swiss border to the Austrian border and back again, the 2026 Milan Cortina Games will be the most geographically dispersed in Olympic history. Gone is one central location for all events and one Olympic Village.

And while past Winter Games, like Turin in 2006 and Vancouver in 2010, have required some city-to-mountain travel, no previous Games resemble this one. This year, athletes, fans, and even the opening ceremonies will be dispersed across venues separated by at least half a day’s travel of bus transfers and train rides. (To be totally accurate, these Games should really be called the 2026 Milan-Cortina-Bormio-Livigno-Tesero-Predazzo-Anterselva-Verona Winter Olympics. But that doesn’t fit as well on posters or sweatshirts – or subway signs.)

This sprinkling of sport across a country may seem like an exercise in expansion, but this year’s multivenue matrix is actually an effort to do the opposite: create a more sustainable Olympic hosting model by prioritizing a region’s existing infrastructure, rather than requiring one city to build billion-dollar structures that will be used once and then left to crumble.

“[The IOC] has been very accommodating with the Milan Cortina bid,” says Victor Matheson, a sports economist at the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, who has written about the economic impact of hosting the Olympics. “They never would have done this 10 years ago. They would have said, ‘Spare no expense, you have to do it all here.’”

For much of the history of the Olympic Games, the international competition begins before any torch is lit, as countries battle for the chance to host the world’s preeminent sporting event. But for the past few games, with cities facing high price tags for little economic returns and opposition from locals, the IOC has struggled to find willing hosts. This is particularly true for the Winter Games, whose geographical requirements, such as mountains, narrow the pool of possible hosts – made narrower still by not only climate change, but also a ballooning Winter Games that’s outgrown the confines of quaint mountainside villages.

In the bids to host the 2026 Winter Games, Austria, Switzerland, and Canada all withdrew, citing political opposition. Japan also withdrew, but largely because its potential host city, Sapporo, was impacted by an earthquake in 2018. Voters in both Sion in Switzerland and Calgary in Canada rejected the bids in public referendums. That left Italy’s Milan Cortina joint proposal, and a similarly dispersed joint bid from Sweden, between Stockholm, the mountainous town of Are, almost 400 miles away, and a sliding track across the Baltic Sea in Latvia.

The 2026 bids followed a few similarly lean cycles. Six countries abandoned potential bids for the 2022 Winter Games, leaving only Kazakhstan’s Almaty and Beijing as contenders. Similarly, several cities dropped out of the 2024 Summer Games bidding, leaving only Paris and Los Angeles. To avoid another embarrassing and potentially economically damaging bidding cycle, the IOC announced Paris for 2024 and Los Angeles for 2028 simultaneously.

“Companies associate the Olympics with some kind of glory,” says Andrew Zimbalist, an economist at Smith College in Northampton, Massachusetts, who has written many books on the economics of sports. “The moment the Olympics start having … images of cities not wanting to host anymore, or the image of politicians complaining publicly [about hosting], all of that is bad publicity and harder to get a return on investment.”

Bigger Games, higher price tags

As recently as the turn of the century, the competition to host was often fierce and sometimes criminal. In their bid to host the 1998 Winter Games, Nagano, Japan, reportedly spent $14 million wooing IOC members. Members of Salt Lake City’s Olympic bid committee faced fraud and bribery charges (later dropped) for bribing IOC members with cash and college scholarships for their children in their efforts to win the 2002 Winter Games. In the following years, nine to 11 cities competed to host the 2004, 2008, and 2012 Summer Games. Flash forward a few years, and the IOC nearly finds itself wooing potential hosts.

That’s largely because the price tag has gotten too high. Almost every modern day Olympics has gone wildly over budget. The IOC and hopeful hosts continue to point to the 1992 Barcelona Olympics as a success story. The city’s infrastructure spending ahead of the Games, combined with the subsequent televised promotions, turned the city’s fortunes and made it the tourism powerhouse it is today.

But not every city can be Barcelona. Recent studies suggest that budgeted tourism figures rarely materialize, as many visitors stay away due to fear of crowds or terrorism. And the back-to-back 2012 London and 2014 Sochi Olympics, the two most expensive Games in history, reaffirmed to many countries that the hosting game wasn’t one they wanted to compete in.

“Because of the successes of the Barcelona Olympics, a lot of cities wanted to bid. That’s when you have bidding wars, and they had to promise much more than they could deliver,” says Robert Livingston, who has covered the bidding process for close to 30 years and produces the website GamesBids.com. “At some point, the bidding process became a victim of its own successes.”

But it’s not just cost that’s winnowed the number of cities raising their hand.

The Winter Games have always been a fraction of the size of their sunnier counterpart, both in the number of sports and athletes. But their growth over the past few decades means that previous hosts, from Lake Placid to Lillehammer, are no longer feasible. Grenoble, in the French Alps, hosted 1,158 athletes across 35 events for the 1968 Games all by itself. This year, the Winter Games will welcome 3,500 athletes across 116 events. More of both will likely be added for the 2030 Winter Games, which will be held in a collection of cities in the French Alps.

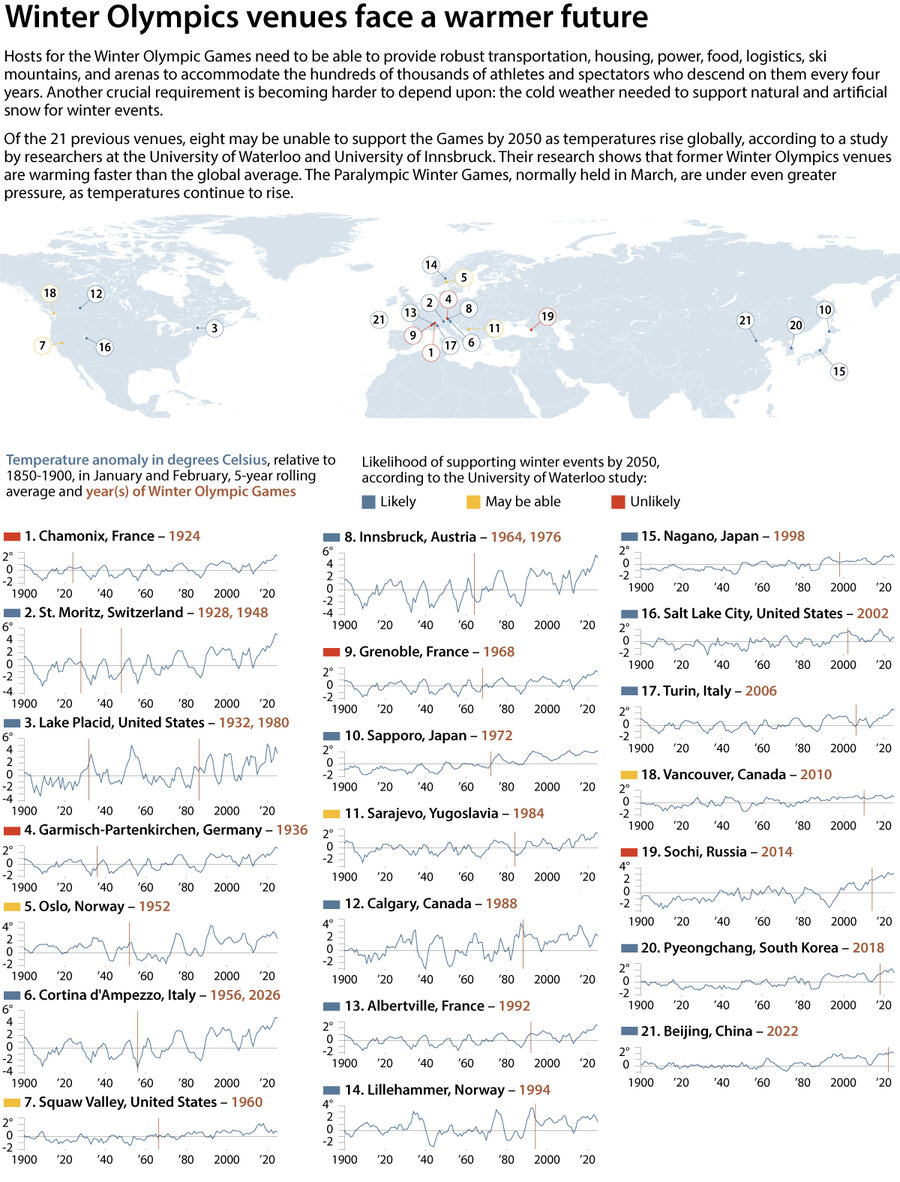

And then there is the issue of climate change.

Winter Olympics venues face a warmer future

Of 21 former Winter Games locations, only 10 to 13 will remain “climate-reliable” by the 2050s, according to a study by Daniel Scott of the University of Waterloo in Ontario, meaning that they can deliver high-quality snow at least 90% of the time. And by the 2080s, this number is expected to drop to eight to 12 locations. For the Paralympic Games, which occur after the Olympics, these numbers drop even further.

“We know [climate change] will affect the geography of where you can host the Winter Olympics and Paralympics. The question is how much,” says Dr. Scott. “It’s tough to find people willing to bid for the Winter Games to begin with, and climate change will reduce the numbers that could, so the two are intertwined.”

Amid these colliding factors, the IOC issued two new criteria in 2022 for future Winter Games hosts: aim to only use existing venues and be “climate reliable” until at least the middle of the century. Under this criterion, there will likely be 10 to 12 countries that will be cold enough and have “at least 80% of the necessary venues” by mid-century, the IOC confirmed in an email to the Monitor.

So here come the 2026 Milan Cortina Games, which are using 85% of existing infrastructure, as the IOC – and the world’s – first test of this new sustainable model.

But Milan is not to be the last. Rather than being fixed in one mountain or city, Olympic “hosts” will now be anchored in the same national – or maybe, one day, border-crossing – spirit that embodies the events themselves. Just look ahead to the 2028 Summer Games in Los Angeles, which will hold softball and canoe slalom events in – drumroll please – Oklahoma City.

“From a practical standpoint, this is absolutely what should be happening. … The economist in me says, ‘Of course we need to spread out the games,’” says Dr. Matheson. “I will say, for their actual participants, fans, and athletes, there is something that is probably lost.”