Kyaw Sai, a schoolteacher from Myanmar’s Shan State, did not recognize a single name on the electronic voting machine in front of him. He pressed a button anyway.

“I voted because I was afraid not to,” he says.

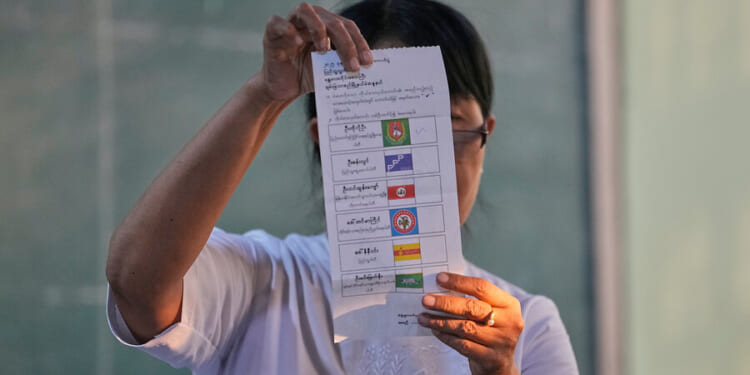

Myanmar was holding its first election since a 2021 military coup overthrew the civilian government led by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Aung San Suu Kyi and plunged the country into civil war, and Mr. Sai knows the process was far from free or fair.

Why We Wrote This

Myanmar’s junta-backed party has secured an overwhelming victory in the country’s first elections since the military seized power in 2021. While the exercise was widely denounced as a sham, some in Myanmar hope it will inch the war-torn country toward democratic norms.

International election watchdogs have dismissed the exercise as a sham designed to legitimize continued military rule. Those allegations were bolstered this past week, when voting concluded and Myanmar’s military-backed Union Solidarity and Development Party declared a sweeping victory. Major opposition groups, barred from the ballot, called for a boycott, arguing that participation only entrenched a system built on coercion.

Still, Mr. Sai hopes the election might introduce at least a minimal check on power in a country that has spent much of its post-independence history under military rule or armed conflict. He’s holding on to a belief that drives citizens to polling booths in autocracies around the world: that these elections, though imperfect, have to be better than nothing.

“It is not an election under ideal conditions, because the military decides who is allowed to run and who is not,” he says. “I don’t believe this election will bring real democracy, but in a country like ours, even a small opening feels better than complete darkness.”

The point of a rigged election

That cautious hope contrasts sharply with Myanmar’s broader reality. Since 2021, around 90,000 people have been killed in the country’s brutal civil war, and more than a million displaced, becoming one of Asia’s worst humanitarian crises.

Ms. Aung San Suu Kyi remains imprisoned, serving a combined sentence of more than three decades on charges that include alleged election fraud. She denies the accusations, which independent observers say lack credible evidence. Her party, the National League for Democracy, along with other major opposition groups, was barred from contesting the election.

In their place, the military cleared the way for parties aligned with its interests, most prominently the Union Solidarity and Development Party.

Voting was also largely confined to areas that are already under firm military control. Myanmar is currently divided between the military and a patchwork of resistance forces, including ethnic armed organizations and militias aligned with the ousted civilian leadership and its parallel administration, the National Unity Government. By December 2024, analysts estimated the junta controlled only about 21% of the country, while ethnic armed groups and resistance forces held more than 40%.

“The election is a political instrument to shore up the junta’s position, not intended to actually increase representation,” says Kim Jolliffe, an independent researcher who specializes in security and humanitarian affairs in Myanmar.

In places such as Belarus, Cambodia, and Egypt, tightly managed elections have long been used less to transfer power than to signal continuity, reassure foreign partners, and cloak authoritarian rule in constitutional form. Some analysts argue that even rigged elections can lead to change by surfacing public grievances and new avenues for dissent. They can also shape how elites and external actors engage with a regime, though critics warn that such processes more often entrench repression than create accountability.

Mr. Jolliffe says Myanmar’s elections follow the same logic, and are primarily aimed at regional governments, banks, and firms that may be seeking a rationale to re-engage without explicitly endorsing military rule.

“It is designed to create the impression that a page is turning,” he says.

It could also advance the ambitions of junta leader Senior Gen. Min Aung Hlaing, who has previously signaled his intention to assume the presidency through a reconstituted parliament.

On its own terms, Mr. Jolliffe says, the election should be judged not by whether it is free or fair, but by whether it strengthens the military’s hold on power. “If it leads to greater international engagement with the regime, boosts confidence among elite allies at home, or weakens morale and external support for the democratic uprising, then it is a success for the junta,” he says.

Voting “under the barrel of a gun”

Gautam Mukhopadhaya, a former Indian ambassador to Myanmar, says the military’s primary objective is to meet the requirements of the country’s army-drafted 2008 constitution and use that legal framework to claim continued authority – particularly in the eyes of key partners such as China and Russia, neither of which has formally acknowledged or endorsed the elections.

“It is an election held under the barrel of a gun,” Mr. Mukhopadhaya says. “All major opposition parties have been disqualified, their leaders are either jailed or in exile, and turnout is very low.”

The junta says voter turnout stood at 52% in the first phase of polling and 56% in the second, which is far below the roughly 70% turnout recorded in Myanmar’s 2015 and 2020 elections, the first broadly democratic national votes after more than half a century of military rule.

Mr. Mukhopadhaya says the military hopes the elections will help it secure at least tacit acceptance from neighboring countries and regional groupings, particularly the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, whose members have long been split over how hard to pressure Myanmar’s generals.

With external backing – or even quiet acquiescence – the junta could intensify military pressure on armed opposition groups, potentially pushing for ceasefires with the involvement of China and other neighbors. That approach may succeed with some ethnic armed organizations, but it is unlikely to bring the more nationalist resistance forces or the ousted civilian leadership to the negotiating table.

“Degree of accountability”

For voters like Mr. Sai, however, the calculations are more immediate. He says the presence of civilian-facing officials, even within a tightly managed system, could make everyday life slightly more navigable.

“Now there are people who are not in uniform, who we can approach about daily problems,” he said. “That creates at least some degree of accountability.”

Granted, those people have all been approved, on some level, by the military, he notes. “But for me, it is still better than having no elections at all.”

Analysts are more cautious. Mr. Jolliffe notes that the current process bears little resemblance to the controlled political opening of 2010–2011, which eventually led to a quasi-civilian government and competitive elections. “The architecture of elections is being used as a smokescreen,” he says.

For now, the war remains the decisive factor shaping Myanmar’s future. Whether the election alters that trajectory – or simply repackages the status quo – will depend less on ballots cast than on battles fought, alliances sustained, and how far regional powers are willing to look beyond the theater of the polls.