With December here and Christmas music blaring, it is worth examining one of the stranger trends to have emerged like flotsam out of the dark sea of social media: Edmund Fitzgerald November. Between Halloween and Thanksgiving, it commemorates the sinking on Lake Superior of the Great Lakes’ freighter the SS Edmund Fitzgerald on November 10th, 1975.

The internet meme has existed for a few years, but it exploded in popularity in 2025 to mark the 50th anniversary of the sinking. Social media was flooded with memes about the wreck, almost always set to the song “The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald” by Canadian folk singer Gordon Lightfoot. Anyone who doubts the scope of the trend should know that, according to Billboard, the song reached number 1 on the Rock charts, Number 2 on Country, and Number 4 in all genres. Not bad for a six-minute-long folk dirge from 1976.

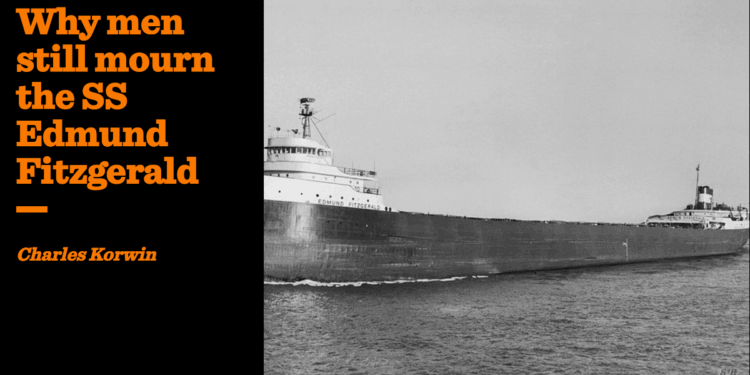

The ship, affectionately known as the Fitz, was a near 750-foot-long freighter which carried iron ore from Wisconsin to plants in Michigan and Ohio at a time when American industry was full speed ahead. On her final passage, she was set upon by hurricane winds, and 35 foot high waves. She sank on the Canadian side of Lake Superior. All 29 men aboard her died. Her Captain’s final transmission was “We are holding our own”. The reason she sank is still unknown.

For complex meteorological reasons, Great Lakes shipping is some of the most dangerous in the world. In fact, the Great Lakes have claimed between 6000 and 10000 ships.

Dubbed the Titanic of the Great Lakes, the Edmund Fitzgerald owes much of its enduring celebrity to the Lightfoot song. It is undoubtedly “a banger”, as the kids might say, with an electric guitar that wails like the “Witch of November”. American humour columnist Dave Berry included it in his Book of Bad Songs, mocking it for “general sappiness and bad rhymes”. He fails to point out that “Does anyone know where the love of God goes when the waves turn the minutes to hours” might be from a hymn.

As part of Edmund Fitzgerald November, covers of the song were shared on social media. Many of the memes poke fun at the idea of men not expressing their feelings, or using a time machine to warn the crew not to set sail. One man dressed as the ship for Halloween. Another common theme is drinking 29 beers for each man aboard her. Predictably, EFN is a very male phenomenon. “They that go down to the sea in ships” will always be a source of interest for men. Consider, for instance, the sea shanty revival that occurred during the pandemic, or the wide acclaim for the film Master and Commander.

An article in GQ argued that the phenomenon is part of an emerging trend of “Leftist Americana”. On the surface, this makes sense. The ship sailed the Great Lakes at a time of economic prosperity in the United States, a time of honest hard work, of good union jobs before deindustrialisation and offshoring — a time when one might say America was great. This is where the “Leftist Americana” argument begins to take on water. The iconography has changed. The Edmund Fitzgerald dates from a time that Trump Republicans and not the US Left are more likely to revere.

It’s a tale from before DEI. The crew were working class men doing a dangerous job which led to their deaths. Men have always looked to tales of heroism, and loss, but this seems very much at odds with contemporary attitudes. Old heroes have been re-evaluated and contextualised by activist historians. To admit an admiration for Lord Nelson’s campaigns, for example, engenders questions about his service in the West Indies and attitudes to slavery. Ditto with a figure like George Washington, statues of whom were torn down during the iconoclasm craze of 2020.

The Edmund Fitzgerald is a socially acceptable historical obsession for men. Captain McSorley’s final words rank with those of Captain Oats for sheer sangfroid. The tale of bravery and loss is the stuff of classic war films which, for numerous reasons, no longer hold the same appeal for younger men as they did for their fathers or grandfathers. In Which We Serve or A Bridge Too Far seem too slow and cheaply made to a generation raised on the latest Marvel CGI extravaganza. It must be admitted that those old war films sometimes have moments that have not aged well. (Guy Gibson’s dog in The Dam Busters immediately comes to mind.)

Watching those kinds of war films is liable to be seen as an early warning sign of extreme right radicalisation. An interest in traditional history is likely as not a cause for deep suspicion. The Second World War was long the historical male obsession “par excellence” but as the conflict fades from memory, the field has developed a cancerous underbelly. It is no longer the safe hobby of middle-aged, middle-class fathers. A new generation is interested in the War for all the wrong reasons. Talk show hosts like Tucker Carlson openly question whether the “right side” won the war. I would not blame a young man for avoiding the field altogether.

Is it any wonder that young men are obsessed with her?

But the Edmund Fitzgerald has none of this dunnage. The drama and the tragedy are so very human. Deckhand Bruce Hudson had recently discovered that he had made his girlfriend pregnant and had committed to moving in with her and raising the child. Captain Ernest McSorley was doing one more trip to pay his wife’s medical bills. In a world where women haters like Andrew Tate have millions of young impressionable viewers, this gallantry and traditional devotion deserve “glad hymns of praise from land and sea”.

The Edmund Fitzgerald sinking led to wide sweeping reforms to the Great Lakes shipping industry. To date, she is the last ship to sink in the Great Lakes. Her tale of peril on the sea ranks with those of Patrick O’Brien and C.S Forester. Is it any wonder that young men are obsessed with her?