Christmas is fast approaching. But in Venezuela, the holidays have been underway for nearly three months already – whether citizens like it or not.

Just days after the first U.S. military strike on a boat allegedly carrying drugs in the Caribbean, leader Nicolás Maduro announced that Christmas was going to arrive early this year. “For the economy, for culture, for joy and happiness … starting Oct. 1, Christmas begins in Venezuela,” Mr. Maduro said on Sept. 8 in his nationally broadcast television program, “Con Maduro +.”

So, on a hot and humid Wednesday in October, out came the Santa hats, the sparkling streetlights, and the bouncy Christmas tunes.

Why We Wrote This

Holidays can provide comfort in the darkest time of the year. But in Venezuela, where this year’s Christmas festivities began early at the behest of authoritarian leader Nicolás Maduro, experts say it’s a distraction.

It’s not the first time a drawn-out Christmas has been used to distract the population from political and economic woes. Last year, Mr. Maduro officially called for Christmas to come early, following weeks of civil unrest over a presidential election which he claimed, without proof, to have won. His predecessor Hugo Chávez declared Christmas in October in 2003, when the country was still recovering from a general strike.

Starting in 2007 and lasting nearly a decade, President Daniel Ortega’s government had the Nicaraguan capital of Managua’s roundabouts decorated with dazzling Christmas trees for all 12 months of the year. This year, El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele passed a law requiring Christmas bonuses be paid out by the end of October.

What these leaders have in common is their authoritarian style of governing. And although decreeing Christmas joy is not part of any traditional authoritarian playbook, it does achieve certain goals that might bolster a leader’s standing, like offering a distraction from a difficult reality or boosting economic activity.

“You could say in the U.S. we’ve moved the holiday season earlier and earlier, too, but that is clearly about consumerism. Whereas this is very political,” says Rebecca Bill Chavez, president and CEO of the Inter-American Dialogue, a think tank in Washington. “They’re trying to project festivity, but that doesn’t match reality.”

Joy and control

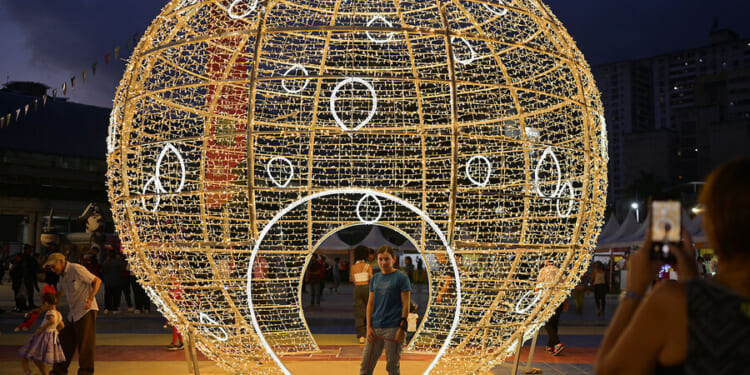

Christmas has long been a cherished time of year in Venezuela. Seasonal specialties like hallacas, a tamale-like dish stuffed with raisins, capers, olives, and meat, are prepared; gaita folk music is played; and carols are sung. Metro stations are decked out with nativity scenes, tree trunks are wrapped in lights with brilliant stars dripping off of branches in public plazas, and government buildings are transformed into canvases for nightly light shows.

Although the early celebrations bothered one government worker, he acknowledges that “at night, the city looks more striking, more cheerful,” he says. Like all Venezuelans interviewed for this story, he asked for anonymity to protect his safety. “In the end, [people] become wrapped up in that sense of magic.”

Despite Mr. Maduro calling early Christmas a “decree,” there are no written guidelines about what is expected or required of the population. One man in Caracas mentioned that the only apartment in his building with its balcony decked out in shimmering lights belongs to a member of the military. At a moment when neighbors are being encouraged to spy on one another and report government dissent through a mobile phone app, fears of fines or looking disloyal aren’t unfounded.

“Everything [government officials] have declared has been verbal,” says a human rights defender in Caracas. “In other words, officials from SENIAT [the tax authority] or the municipality can tell merchants they have to put up decorations, and if they don’t … they will inspect them and sanction them for tax-related noncompliance” and there’s little a civilian can say to push back.

The government employee says he was required to purchase holiday T-shirts with $10 of his own money – a high price in Venezuela’s moribund economy – and for the first two weeks of October had to dedicate the last hour of each work day to office dance parties with live Christmas music.

“Everyone in the public sector mobilizes and complies,” because they fear their jobs are on the line, he says.

Kurt Weyland, a political science professor at the University of Texas at Austin, puts the early Christmas moves in the same category as dictators in Brazil and Argentina using big soccer wins to project images of strength and development in the 1970s.

“These are distractions,” Dr. Weyland says. “It’s less about bringing joy and more about control.”

“Viva la pepa”

Experts say Mr. Maduro’s Christmas decree is meant to distract Venezuelans from U.S. military threats, one of the worst economic contractions in the world, and a daily struggle to put food on the table. He may also be hoping to boost consumption in a faltering economy, but few Venezuelans have the means to consume more. Venezuela’s gross domestic product contracted by more than 80% between 2013 to 2020, and inflation is extremely high, eroding wages and purchasing power.

Early Christmas might be more effective as an authoritarian tool if it included government handouts, like much-needed food or medical supplies, says Dr. Chavez, who studies democracy and authoritarianism. The central toolbox of authoritarianism has been “perfected over time,” and includes things like changing the constitution to allow for reelection or playing with term limits, controlling Congress, stifling the media, and taking away the independence of the judiciary.

Christmas alone, as a tool, “is unlikely to work,” she says.

Venezuelans are very aware that there’s a conflict brewing between Mr. Maduro and U.S. President Donald Trump, says a Caracas-based photographer. But it’s also necessary to try to carry on with their lives as normally as possible, he says.

“We celebrate, we have fun, and we wait for things to pass,” he says. “It’s the ‘viva la pepa’ attitude,” a Venezuelan expression akin to “whatever happens, happens.”