The political landscape of the Western alternative right is marked by a curious paradox: an unexpected sympathy toward Russia’s aggression against Ukraine. I use the term alternative right here and throughout the essay not in reference to what is commonly known as the “alt-right,” but rather to describe various right-wing currents in the Anglosphere that diverge from the mainstream and are primarily known for their criticism of it. For instance, diverse figures such as Curtis Yarvin and Tucker Carlson have expressed sympathy for Russia over Ukraine.

Brendan O’Neill has observed that a segment of the political right exhibits what he terms a “Zelensky Derangement Syndrome”, which, he argues, “eerily mirrors the frenzied loathing for Israel that has been infecting leftists for years.” This position is, historically speaking, quite rare. European right-wing movements have seldom drawn inspiration from Russia, more often perceiving it as a threat, even in its pre-communist form as the Russian Empire. Even before the rise of communism, Western states usually perceived Russia as a threat, viewing its imperial ambitions as fundamentally destabilizing. Even when revolutionary Napoleonic France was threatening conservative regimes across Europe, many within those same regimes regarded Russia as the greater long-term danger. As Dominic Lieven notes in his Russia Against Napoleon, “there were influential figures in Vienna who saw Russia as a greater threat than France because Napoleon’s empire might well prove ephemeral whereas Russia was there to stay.”

As for the communist Soviet Union, there is, of course, no need to elaborate on the hostility it inspired among the European right. Today’s Russian regime, however, employs symbolism and narratives that are unmistakably closer to that Soviet legacy, making the current fascination of some Western right-wing figures with Moscow all the more puzzling.

This stance seems almost counterintuitive, given the values and ideologies the alternative right claims to champion — nationalism, militarism, cultural homogeneity, and resistance to imperial overreach. Yet, rather than aligning with Ukraine, a nation embodying these very principles in its struggle against a larger, more heterogeneous foe, many Western alternative-right factions have instead expressed admiration for Vladimir Putin’s Russia. This misalignment is not only puzzling but also a missed opportunity. Ukraine, in its defiance and resilience, should serve as a model for the alternative right in the West. It is far closer to their stated ideals than Russia ever could be.

A Heroic Struggle and Militarism Against a Stronger Foe

At the heart of Ukraine’s resistance lies a story of heroic struggle — a narrative that should resonate deeply with the alternative right’s romanticized view of the nation. Since Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 and the full-scale invasion in 2022, Ukraine has faced an adversary with superior military resources and a larger population. Yet, despite these odds, Ukraine has not only held its ground and an unyielding national spirit. More than that, Ukraine’s fight stands in stark opposition to the calculative rationalism that characterizes the Enlightenment ideologies the alternative right claims to critique. Where the liberal progeny of the Enlightenment might weigh costs and benefits, seeking pragmatic surrender or compromise, Ukraine has chosen to fight against the odds, driven not by cold logic but by ideals of honour and survival.

The mockery of Volodymyr Zelensky in his military fatigues, often a cheap jab from detractors, becomes bitterly ironic when one considers his actions. This is a man who stayed in Kyiv at a moment when the city could have fallen, when Russian forces were close enough to potentially execute Ukraine’s political elite. Instead of rallying behind a leader who chose to remain in his country at a moment when his life was at imminent risk, despite being offered the chance to flee, the self-proclaimed admirers of Bronze Age warriors and champions of youthful vitality have aligned themselves with a seventy-two-year-old man who fantasizes about living another fifty years or more, and who spent the COVID-19 years largely hidden from public view, avoiding encounters. Take his handling of Yevgeny Prigozhin, the Wagner Group leader who briefly rebelled in 2023. Putin struck a deal to end the mutiny, only to apparently eliminate Prigozhin months later in a plane crash. Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov reported on the meeting between Prigozhin and Putin following the end of the rebellion, saying: “He also gave an assessment of the June 24 events. Putin listened to the commanders’ explanations and suggested options for their future employment and their potential use in combat”. This betrayal flies in the face of any ancient code of honour, be it the medieval chivalric pact between knights or the warrior ethos of antiquity where agreements were sacred. As the Romans held, “Pacta sunt servanda” (agreements must be kept), a principle Putin discards with cynical disdain. For an alternative right that often lionises the integrity of old-world masculinity, Zelensky’s steadfastness should command respect, while Putin’s duplicity should provoke disdain.

This rejection of bloodless rationalism and embrace of honour should strike a chord with the alternative right’s self-styled Nietzscheans and devotees of figures like Bronze Age Pervert (BAP), who revel in the aesthetics of ancient heroism. They often invoke the legacy of antiquity, where glory was won through defiance, not negotiation. As the old Latin poet Horace wrote, “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori” (it is sweet and fitting to die for one’s country) a sentiment that echoes in Ukraine’s unyielding stand. Likewise, they might recall Pericles’ Funeral Oration to the Athenians, as recorded by Thucydides, where the Athenian leader extolled the courage of those who faced death willingly for the polis, urging his people to emulate them. “I believe that a death such as theirs has been the true measure of a man’s worth”, Pericles said. Ukraine’s soldiers, dying in muddy trenches or urban ruins, embody this spirit, not as a theoretical exercise but as a lived reality.

A Homogeneous Nation Against a Heterogeneous Empire

The Israeli political theorist and advocate of nationalism, Yoram Hazony, published several years ago his influential book The Virtue of Nationalism. In this work, Hazony argues that nationalism should serve as the organising principle of the international order. According to his thesis, nationalism stands in direct opposition to imperialism. From this perspective, imperial projects, by their very nature, lead to domination, coercion, and ultimately to the eruption of conflict and instability.

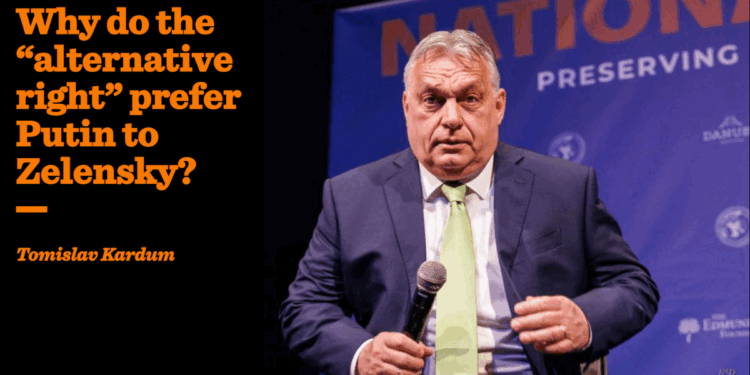

It is therefore striking that Hazony, in his otherwise highly insightful book, The Virtue of Nationalism, makes no reference whatsoever to the war between Russia and Ukraine despite the fact that this conflict fits almost perfectly into his theoretical framework. It’s worth noting that the book was published before the full-scale invasion but the conflict has been ongoing since 2014. Equally noteworthy is the broader National Conservatism movement, in which Hazony is one of the key figures, and which has convened several high-profile international conferences in recent years. For reasons that remain unclear, this movement has been conspicuously muted in its criticism of Russia, often adopting a notably “soft” stance toward Moscow. Following the invasion, Hazony expressed support for Ukraine in a conference speech (though, at first, various figures such as Tucker Carlson also appeared to side with Ukraine, only to rebound). But the wider conference failed to fully utilise the positive example of Ukraine. While it is understandable that nationalists, guided by their own domestic priorities, may not feel compelled to issue pronouncements on every global conflict, it is nevertheless unusual for them not to strongly position themselves against an imperial power.

This ambivalence is particularly puzzling given that the Russian state has, on numerous occasions, been offered opportunities for constructive engagement by Western actors. Despite these gestures, President Vladimir Putin has recently articulated a worldview that is fundamentally hostile to nationalism as such. In a recent statement, he declared that nationalism represents “the first stage toward Nazism.” He went on:

Nationalism is based not simply on love for members of one’s own ethnic group, but on hatred of others. That is the essence of nationalism. Patriotism is a completely different matter. Loving one’s homeland does not mean hating others.

Perhaps the most striking reason Ukraine should resonate with the alternative right is its relative cultural and ethnic homogeneity, pitted against the sprawling, multiethnic empire of Russia. The alternative right in the West has long championed the preservation of national identity. Russia’s heterogeneity is not a source of strength but a liability, exposed by reports of discontent among its minority populations and the disproportionate casualties borne by ethnically non-Russian conscripts. This imperial mosaic stands in stark contrast to Ukraine’s more unified front, where the war has galvanised a collective sense of purpose. For alternative-right ideologues who decry multiculturalism and the erosion of national cohesion, Ukraine’s fight should have a strong appeal — a homogeneous nation resisting the overreach of a chaotic, multiethnic empire.

Yet, the Western alternative right’s fascination with Russia persists, often rooted in a superficial admiration for Putin’s rejection of so-called liberal globalism. However, Russian President Vladimir Putin employs civilisationalist rhetoric in his confrontation with the West, positioning Russia as part of a global coalition of civilisations united against Western dominance. This narrative frames the conflict not merely as geopolitical but as a fundamental clash between different civilisational orders. This raises a key question: how can one form a genuine alliance with actors who are, from the outset, defined as adversaries within this worldview? Canadian historian Paul Robinson, in his recent book Russia’s World Order: How Civilizationism Explains the Conflict with the West, provides an insightful analysis of how this civilisationalist approach operates. He argues that:

Russian leaders describe it as a struggle between those who believe in a world made up of diverse civilizations and those who believe that there is but one civilization, represented by the West, and as a struggle between those who believe that history marches in many directions and those who believe that it marches only in one. Each of these framings appeals to a different constituency. The talk of autocracy versus democracy plays an important role in rallying support for the struggle against Russia in the West. It also helps bind Western states together, creating a common identity against the autocratic “other.” It is therefore a framing that is primarily directed inward. The weakness of this framing is that it seems to have little appeal outside the West. By contrast, Russia is looking outward, seeking to generate support, or at least neutrality, among non-Western countries.

Sergey Karaganov, arguably one of the most influential political theorists within Vladimir Putin’s intellectual orbit and honorary chairman of the Russian Council for Foreign and Defence Policy, published an essay early this year in Russia in Global Affairs entitled “Breaking Europe’s Back: What Should Russia’s Policy Be Toward the West?” The title itself is revealing, as it encapsulates the essay’s central thesis: Europe is portrayed in explicitly essentialist terms as an irredeemable and permanent enemy of Russia. In this vision, Russia is no longer conceived as part of the European civilisational space but rather as a distinct entity locked in existential conflict with it. Karaganov argues that Russia should seek to provide the United States with a path to disengage from the war while simultaneously “breaking” Europe’s political will. Particularly striking is his description of Europe as the ultimate source of global evil. His characterisation of European history, as a record of colonialism, genocide, racism, and oppression, paradoxically mirrors the rhetoric often associated with segments of the contemporary Western left, especially within so-called “woke” discourse. Thus, while alternative-right actors in the West sometimes imagine Russia as a traditionalist and anti-woke bastion, Karaganov’s own narrative draws upon themes that resonate with the leftist critique of Western civilization itself. Karaganov writes:

Europe is the source of all of humanity’s major misfortunes: two world wars, genocides, anti-human ideologies, colonialism, racism, Nazism, and the list goes on. The well-known European bureaucrat’s metaphor of Europe as a “blooming garden” sounds alternative more realistic if we describe it as a field overgrown with lush weeds, thriving on the muck of hundreds of millions of murdered, robbed, and enslaved people… Europe must be called by its proper name, to make the threat of using nuclear weapons against it more credible and justifiable.

For those interested, there is also a 24-part “course” on Russian history available on YouTube by Vladimir Medinsky, historian and former Minister of Culture, now serving as one of Putin’s aides. Beyond the familiar denial of the Ukrainian nation and the appropriation of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania as a “Russian” state, Medinsky’s narrative consistently frames the greatest threat to Russia as coming from the West — whether it be a Polish-Vatican conspiracy, Napoleon, Hitler, or the United States. Russia is depicted as a fundamentally benevolent empire, non-racist in contrast to Western empires, with smaller nations supposedly joining it willingly rather than through coercion.

This rhetoric portrays Russia as fundamentally distinct from the West, a framing that is not merely ideological but deeply rooted in the historical experience of Russian governance. As historian Orlando Figes observes, “the single greatest difference between Russia and the West, both under Tsarism and Communism, was that in Western Europe citizens were generally free to do as they pleased so long as their activities had not been specifically prohibited by the state, while the people of Russia were not free to do anything unless the state had given them specific permission to do it.” This fundamental divergence helps explain why it is deeply paradoxical for segments of the Western far right to idealize Russia as a model, given that the Russian state tradition is based on principles antithetical to the values they claim to defend.

The alternative right’s sympathy for Russia is a perplexing detour from its own principles. Ukraine’s war is a living testament to the values of nationalism, martial honour, and cultural preservation, values the alternative right claims to uphold. Its soldiers fight not for abstract ideology but for the tangible reality of their homes and homeland. Its leaders invoke history not to appease foreign powers but to assert their sovereignty. Its people rally not as a disparate coalition but as a unified nation. These are the traits the alternative right should celebrate, yet too often, it turns its gaze toward Moscow instead.

This misalignment probably stems from a broader disillusionment with Western liberalism, leading some to see Russia as a counterweight to progressive excesses. But such a view is short-sighted. Russia’s war is not a defense of tradition but an exercise in anti-Western imperial domination against values the alternative right claims to revere. Ukraine, by contrast, offers a purer distillation of their ideals, a nation fighting for its existence against a larger, more powerful foe. For the alternative right to reclaim ideological consistency, it must look to Kyiv, not Moscow. Ukraine’s struggle is a mirror held up to their own rhetoric, reflecting the courage, unity, and defiance they so often extol. To ignore this is to betray the principles they profess to hold.