Vases of flowers and notes scribbled with messages of support are scattered throughout Hana Kim’s home in Goodyear, Arizona. Her friends and family sent them after she announced her decision to leave her job.

Ms. Kim left her role as a marketing executive at an insurance carrier on Dec. 1, after months of stricter in-person work requirements and a long commute to Phoenix made it difficult for her to maintain the care she provides to her mother at home.

“I felt like it was a decision that could have been avoided if the company were more about flexibility and met different kinds of employees’ needs,” says Ms. Kim, who was originally hired to work remotely.

Why We Wrote This

Shifts in workplace policies, like a pullback from remote and hybrid work launched during the pandemic, appear to be creating a tough year for women in the U.S. workforce.

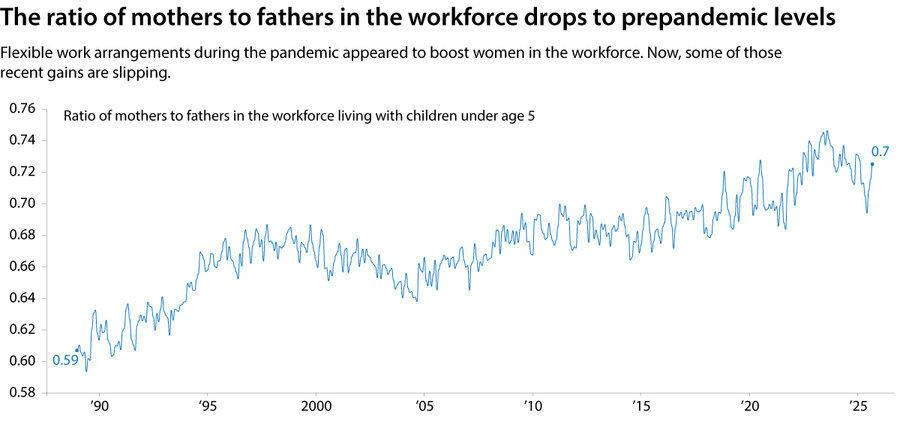

Ms. Kim is part of a movement of women who are leaving their jobs. More than 330,000 women ages 20 or older have left the workforce this year, according to an analysis by the National Women’s Law Center. In the first half of 2025, the employment rate of mothers of children under age 5 declined by its steepest drop in four decades, according to research by Misty Heggeness, an associate professor at the University of Kansas who studies gender economics.

“The past year brought unusual pressures for employees and the highest levels of discontent in five years,” noted a recent report on women in the U.S. workforce by Lean In, a women’s advocacy group, and McKinsey & Company consultants.

Return-to-work mandates, a federal rollback under the Trump administration of diversity, equity, and inclusion policies, including some geared toward women, and a shortage of affordable care for dependents are all affecting whether women stay on the job, says Jasmine Tucker, vice president of research at the National Women’s Law Center in Washington.

“The trends over time are not looking good,” says Ms. Tucker. “We say ‘leaving the labor force,’ and it sounds like it’s an option, but I think the reality is that they are being shoved out.”

Not everyone views a pullback of women from the paid labor force negatively. Popular right-wing podcasters like Allie Beth Stuckey and Alex Clark talk about the benefit of mothers prioritizing time with their children and say societal norms put too much pressure on women to put their careers first.

Facing the “flexibility stigma”

During the pandemic, remote or flexible work helped usher some women into the workplace. In 2023, the percentage of prime-age working women (in the 25-to-54 age range), reached an all-time high of 75.3%, driven largely by an increase of college-educated women with young children.

Many employers this year retreated from the remote and hybrid work that was infused into certain professional roles during the COVID-19 pandemic. The federal government required employees to return to five days in office, as did Amazon for its corporate staff. One study found that more than half of Fortune 100 workers this year had fully in-person policies for the first time since the pandemic.

The Lean In and McKinsey report published last week found that one-quarter of 124 companies surveyed reported scaling back or discontinuing remote or hybrid work this year. A flexibility stigma is one of the “biggest factors holding women back from work,” according to the report’s authors, who found that employees who use flexible work arrangements are seen as less committed and are less likely to receive promotions or sponsorships.

At the same time, costs of both child care and elder care are rising faster than inflation, which puts pressure on individuals to decide whether they can afford to remain in the workforce.

“In two-parent households, when we can’t afford the cost of child care, we usually send the person who is the lower-income earner home to take care of the kids,” says Jessica Kriegel, chief strategy officer at Culture Partners, a consultancy group. “That affects women,” she adds, since the pay gap between genders has grown for the past two years. In addition, she notes, about 80% of single parent households are headed by women.

Looking for solutions

Views on how to help women – and men – balance professional work with caregiving responsibilities range from greater child care support to more tax credits for parents.

Last month, New Mexico became the first state to provide universal, government-funded child care for all families, regardless of income, using funding from state oil and gas reserves. New York’s incoming mayor Zohran Mamdani campaigned on a promise of universal child care.

At the federal level, the tax and spending bill passed by Congress over the summer included several provisions meant to support working families. Those include a permanent extension of the child tax credit, increased tax credits for employers who provide child care assistance, and tax-advantaged savings accounts for children known as “Trump Accounts.”

Policymakers can offer support by investing in parental leave and high-quality, affordable child care, subsidized by the government, says Professor Heggeness at the University of Kansas. “Mothers and unpaid family caregivers, that group of individuals in our society, are too big for us to fail them,” she says.

Critics of universal child care raise concerns about funding, quality, and the impact on children. Vice President JD Vance, while running for Senate in 2021, wrote an op-ed in The Wall Street Journal criticizing a Biden administration proposal to spend $225 billion on child care as harmful to children. (Other studies show high-quality early childhood benefiting children academically and socially.)

“Young children from average, healthy homes can be harmed by spending long hours in child care,” Mr. Vance wrote. “Our democracy might be comfortable with the trade-offs here – higher gross domestic product and more parents (especially women) in the workforce on one hand, and unhappier, unhealthier children on the other. But we ought to be honest and acknowledge that these trade-offs exist.”

Dr. Heggeness expects the labor participation rate for women to rebound. “Women, and mothers in particular, tend to be very resilient,” she says. “Women will look for other ways to get back into work.”

“It feels really gratifying”

Ms. Kim in Arizona believes she made the best decision she could for herself and for her family, despite initially feeling as if she was giving up on a career that she “worked so hard to get.”

Shortly after leaving her corporate job, she launched her own marketing consultancy, fending off her self-doubt about leaving a steady paycheck and focusing on the control she’d gain over her schedule.

When she decided it was time to pack up her office, Ms. Kim posted about her decision online. Her post gathered more than 2,000 likes and 250 comments. Her private messages filled up with other women who left their jobs to provide care for loved ones, telling her she wouldn’t regret her decision.

“There was a second that I was thinking … maybe this is crazy,” she says. “I’m just trying to do what I know how to do and do it on my own terms. It feels really gratifying.”