A federal judge sentenced a former Louisville, Kentucky, police officer to 33 months in prison, with three years of supervised release, for his role in a botched raid that accidentally killed Breonna Taylor five years ago.

The sentence for Brett Hankison, which came after the U.S. Department of Justice had suggested a punishment of one day in prison, closes the book on a case that helped spark nationwide calls for racial justice and police reform. But it leaves behind lingering concerns over the difficulties in bringing charges against individual officers in excessive force cases, as well as how politically polarized the debate over police reform in America has become.

“There was no prosecution in there for us; there was no prosecution in there for Breonna,” said Tamika Palmer, Ms. Taylor’s mother, after the hearing. “We could have walked away with nothing for what they recommended. [But] we’re still here, and I’m grateful that something happened.”

Why We Wrote This

A police officer involved in the raid that killed Breonna Taylor in 2020 was sentenced today. The Department of Justice’s approach to the case points to a retreat from police reform efforts.

In 2020, a police tactical unit killed Ms. Taylor, a Black emergency room technician, while executing a “no-knock warrant” on her apartment. Mr. Hankison, who is white, is the only officer involved in the raid to have been convicted of a crime. After the Biden Department of Justice successfully prosecuted Mr. Hankison for abusing civil rights, DOJ leadership under President Donald Trump performed a dramatic about-face last week, recommending to Judge Rebecca Grady Jennings a sentence of one day in prison. The Biden administration had recommended an 11-to-14-year sentence.

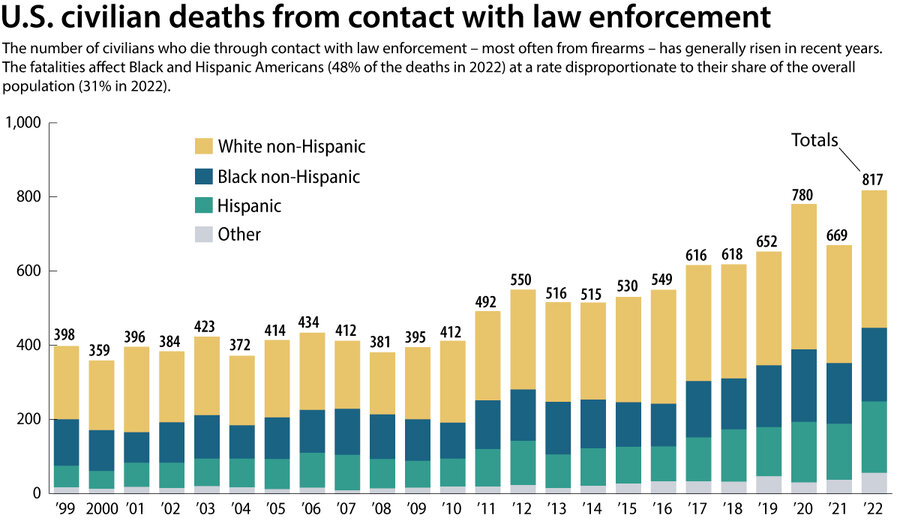

The sentencing recommendation came amid a monthslong effort by the Trump administration to reverse policies set up under former Presidents Barack Obama and Joe Biden to tackle national concerns that U.S. police had become too quick to use violence, especially when dealing with Black suspects. Ms. Taylor’s death – along with the death of George Floyd in Minneapolis – helped fuel nationwide protests against police brutality in 2020. Those followed earlier protests after the police-related deaths of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, and Eric Garner in New York, both in 2014.

But these protests, crime spikes in cities where police were highly criticized, and the large number of Americans killed by police every year have provided voters with what sometimes seems like a binary choice: Demand accountability and invite lawlessness, or defend police and unleash excesses of force. Those involved in police reform say lasting solutions require both systemic improvements and individual accountability when things go wrong.

“It’s unfortunate when police accountability gets tied to partisan projects,” says Ian Adams, a former police officer in Utah who is now a criminologist at the University of South Carolina.

“I don’t know that social sloganeering is how we should be approaching either side of police accountability,” he adds. “Neither ‘Back the blue’ nor ‘Say her name’ captures the importance of what we’re doing here.”

A push for reform – and an about-face

A decade ago, President Obama began America’s modern police-reform push. He formed a Task Force on 21st Century Policing. His administration urged police departments to adopt body cameras and drastically increased the number of federal consent decrees aimed at reforming specific departments.

The Biden administration ramped up these policies, partly in response to public pressure after the deaths of Mr. Floyd and Ms. Taylor. The Justice Department brought federal charges in both cases. In announcing Mr. Hankison’s conviction, Kristen Clarke – then the assistant attorney general for civil rights – encouraged people to “Say her name,” echoing a slogan that protesters used after Ms. Taylor’s death.

President Trump campaigned on a promise to take a very different tack on policing issues, and that promise has been fulfilled in the Hankison case and beyond. He has said that “one real rough, nasty day” of policing would end retail theft, and he described police clearing out campus protesters at Columbia University as “a beautiful thing to watch.” In an April executive order, he called on his administration to “unleash high-impact local police forces,” as well as “protect and defend law enforcement officers wrongly accused” of crimes.

One of his first acts in office was to pardon two Washington, D.C., police officers convicted for their role in a fatal police chase.

In Mr. Hankison’s case, the jury verdict last year left him facing a maximum sentence of life in prison. Career prosecutors who try cases typically submit sentencing recommendations to judges, but in this case, the recommendation came from their boss, Harmeet Dhillon, the assistant attorney general for civil rights.

In a court filing last week, Ms. Dhillon argued that after three trials – only one of which ended with a conviction – as well as the psychological stress of five years as a criminal defendant, any more time behind bars would be unnecessary and unfair.

The conviction “will almost certainly ensure that Defendant Hankison never serves as a law enforcement officer again and will also likely ensure that he never legally possesses a firearm again,” she wrote.

“Adding on top of those consequences a [lengthy] sentence … would, in the government’s view, simply be unjust under these circumstances,” she added.

After the hearing, Ms. Taylor’s family members and their lawyers expressed both relief at the verdict and dismay at how the Justice Department had handled the final stage of the case. Ben Crump, one of the family’s attorneys, described it as being “like a George Orwell story.”

“Never in my career as a lawyer have I heard a prosecutor argue so adamantly for a convicted felon,” he added.

The arguments involve a traditional debate among lawyers regarding sentencing. Does a sentence need to send a message to the specific individual being sentenced? Or does it need to send a message to society more broadly?

“You could say this is a man who, outside of his policing job, has not posed a threat of harm to the public, so why should he be in prison?” says Rachel Moran, a police accountability expert at the University of St. Thomas School of Law.

“But as a symbolic matter, the DOJ is well aware that they’re also implicitly saying, ‘We do not want to make an example of this officer, and, in fact, we are doing the opposite’ by requesting a one-day sentence,” she adds.

What climate now in local communities?

But decisions like the one in the Taylor case suggest that shifts in federal outlook can have a significant impact on local communities. There is a federal spigot of law enforcement money that can be redirected or squelched at the direction of the administration. And even in liberal states, there is a growing sense that police should have freedom to do their jobs as long as there are solid accountability measures in place.

A focus now is on what could become of some of those accountability measures under the Trump administration.

One such measure is a consent decree, a legal contract agreed upon between a police department, its local government, and the Department of Justice after the agency has found evidence of civil rights violations. Project 2025, a conservative blueprint for this Trump administration, called for the end of consent decrees, describing them as “brazenly partisan and ideologically driven.” The Trump administration has since ended all consent decrees that the Justice Department was engaged in, including one with the Louisville Police Department and one with the Minneapolis Police Department.

Meanwhile, the DOJ’s Civil Rights Division, the section responsible for handling police misconduct prosecutions, has been facing an exodus of staff.

Since January, more than 250 attorneys in the division – about 70% of its personnel – have left or are planning to go, according to news reports. Political appointees who had been encouraging civil rights attorneys to take buyouts have recently begun asking career officials to return, The Guardian reported last month. The six DOJ attorneys overseeing a consent decree with the New Orleans Police Department, for example, are among those who have left the agency.

Ultimately, experts say, successful police reform needs to marry individual accountability with systemic improvements.

“If you only pursue one track, the other falters. Systemic reforms without credible individual sanctions breed cynicism, while charging officers without structural reform guarantees a revolving door of future cases,” says Thaddeus Johnson, a former police officer and now a senior fellow at the Council on Criminal Justice.

“Reframing police reform as a public‑service modernization project, similar to aviation‑safety overhauls, helps mitigate partisan reflexes.”