When things were at their worst, Miia Huitti would just go into the forest, sit on a stone, and cry. “I’ve always been a perfectionist,” she says, and things were far from perfect.

The career-driven Finn wanted to be one of those mothers who was back in the office as soon as her maternity leave ended. But then she had three children in 13 months, including twins born premature and needing care. They woke up six to 10 times a night, and then her husband discovered the house was infested with mold.

She had thoughts of suicide, of divorce. “I wanted to get out of my life.”

Why We Wrote This

A story focused on

Finland has ranked the world’s happiest country for years. But that doesn’t mean Finns are a smiling, perky people. Rather, Finnish “happiness” points to something else – a contentment and reassuredness that few others can match.

But even then, those moments of quiet in the forest were beginning to heal her. As she found space to step back from the burden of all the expectations – “the perfect mother, the perfect spouse” – she learned to let go.

Looking back now, she says what she needed to learn was simplicity – being grateful and content with what she had. And one of her best teachers was Finland itself, inspiring her to found the Finnish Happiness Institute.

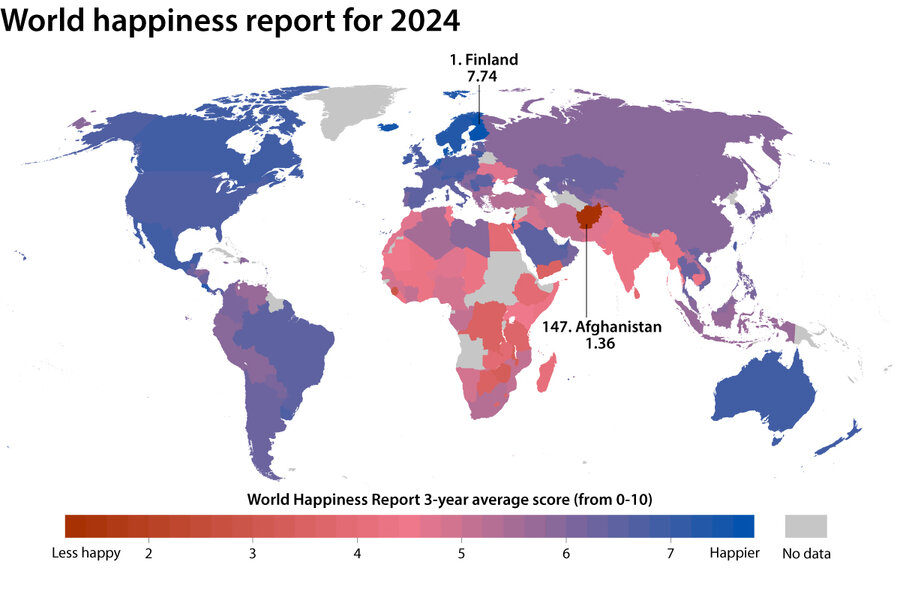

This year, the World Happiness Report again named Finland the world’s happiest country, something that has become a regular occurrence. Yet “Finland” is hardly synonymous with “happy” worldwide. Finns often give a bemused grin when the survey is mentioned.

Even the researchers behind the survey acknowledge that there is no one definition of happiness. What they are really measuring is quality of life, not only by material measures but mental ones. Do you feel safe? Do you trust those around you? Are you free to shape your life as you wish? In that way, Finland becomes something of a Rorschach test for what happiness is.

No one – not least the Finns themselves – would say they are the most joyful people. But Ms. Huitti’s climb out of darkness speaks to something else.

“It’s not that you have to be joyful all the time,” she says. “You can’t see the stars if it’s light all the time. It’s an inner sense that you can be happy no matter the circumstance.”

On this, most Finns agree with the survey. Their country is special. The question for the rest of the world is: How do they do it?

“I’m not thinking, ‘I’m so happy!’”

The men clad only in bathrobes outside Kotiharjun Sauna in Helsinki have thoughts. The scene could be the beginning of a joke: “A journalist walks into a Finnish sauna …” Someone makes the assertion that Finland is the world’s happiest country. Laughter ensues. Despite the good-natured banter pinging among the benches where men gather outside after a good steam, no one says Finland should be mistaken for a country of happy extroverts.

“In daily life, I’m not thinking, ‘I’m so happy! I’m so happy!’” chortles Juhari Lehtiranta.

But the longer they chat, the more they seem to persuade themselves.

Ilmari Lappalainen folds his arms pensively as he talks. Yes, Finns are happy, he says, but it’s a different sort of happiness.

“We do like to complain about stupid things, but in the end we’re content with how things are, and not aiming to get everything,” he says. “There’s no point bragging about what you have. We are trusting our authorities and each other.”

The others nod appreciatively. Somewhere, John Heliwell is probably nodding his head, too. As an author of the World Happiness Report, he says this is one of Finland’s distinctions. “When you’re thinking about the evaluation of life as a whole, you don’t expect that to show up on people’s faces,” he says. Finns “spend less time evaluating themselves with their success relative to others. It builds a bigger ‘we.’”

The men outside the sauna feel that. They say Finland’s welfare state is an expression of that larger “we,” built on a sense of safety and mutual care.

With the rebellious blond hair of the punk he says he once was, Aleksi Pylhhänen recalls the time he worked in Australia and his boss refused to pay him $700 he felt he was legally owed. “There was no one to go to,” he says. “Here you have 100 places to call. Someone does care if something goes wrong.”

That sense of security is essential to happiness. Elisabet Lahti has traveled the world for years talking about sisu, the Finnish concept of grace and power under adversity. But she gained a new appreciation for her homeland when dealing with a corrupt immigration official abroad. “For me to come back here, I’ve seen what it did to my sense of safety,” she says. “A calm mind is a content mind, and a content mind is a happy mind.”

In many respects, living in Finland simply makes life easier. Dylan Sturdy, an Irish expat at the sauna, recounts the decision he and his Finnish girlfriend made about where to live. They found 450 apartments available for less than €1,000 a month in the neighborhood they liked in Helsinki. In Dublin, they found one under €1,500.

“All the opportunities are so much better here,” he says.

Nature and solitude

That support helped Ms. Huitti out of the depths. For example, the state paid for three hours of childcare a week. It was small, but it allowed her to get out into nature. And that is where the healing began.

Again and again, studies show a clear link between nature and mental well-being. For Finns, it is a place to commune with sustaining beauty and quiet. And for Ms. Huitti, it was a place to begin reassembling herself. “Nature is very valuable to us Finns,” she says. “It’s a place we can calm down. We can be quiet and alone. Going to a Finnish cottage by a lake with no power and no running water, that’s where we’re happiest.”

Mr. Lappalainen from the sauna couldn’t agree more. “I don’t want a nice, fancy car. I want the forest next to me.”

Of course, Finland has had its problems, too. Rates of alcoholism, male suicide, and loneliness have been high, though they are improving. And then there is the whole talking-to-strangers thing.

Expat Jukka Savolainen moved back to his native Finland from the U.S. when his son was born, but he didn’t stay long.

“When I went to the playground, I was expecting to talk to parents and for the kids to intermingle, but none of that happened,” he says. “Then I moved to Nebraska, and our neighbors invited us over to their hot tub and their daughter was advertising her babysitting services before we moved in.”

He’s now a professor at Wayne State University in Detroit. Welfare states do a good job of eliminating abject misery, he says. But is that happiness? Finland is very high on decency, he adds. “It has very equal public policy, rational and humane. … But I prefer the American way of life. A big source of happiness is being in a community.”

All say that happiness, on some level, is in the eye of the beholder. Now as the founder of the Finnish Happiness Institute, Ms. Huitti just wants people to slow down and think about it more – and she thinks Finland offers useful lessons.

Back at the sauna, Mr. Pylhhänen gives a roguish grin and says he has found the answer to the “happiest country” debate – in a very Finnish way, of course.

“We are the least-failed state.”