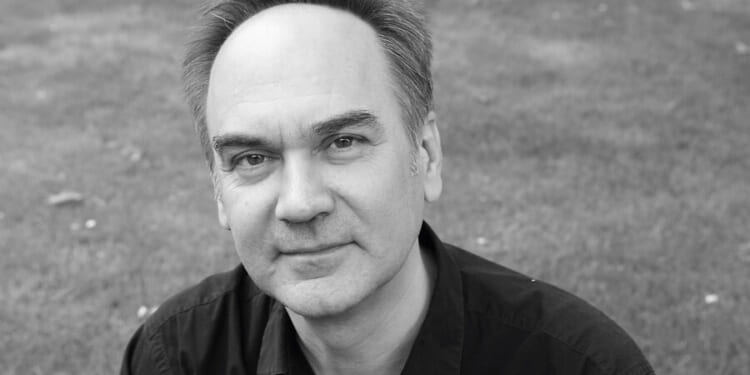

When French author Hervé Le Tellier went in search of a new country house, he told his real estate agent that he wanted neither a fixer-upper nor a fancy villa. Instead, he dreamed of a “childhood home,” a place where he could plant roots, something he had been unable to do growing up with an unstable mother, an absent father, and no siblings.

Le Tellier ended up with not only a house but also a historical mystery. Underneath one of the ceramic plaques on the outside wall of his home in Montjoux, in the Drôme region of France, a name was etched: André Chaix.

At first glance, the last name Chaix meant very little to Le Tellier. It wasn’t until he was roaming around Montjoux that the puzzle started to click together. There, on a monument dedicated “to the memory of the children of Montjoux who died for France” was the same name: CHAIX ANDRÉ (May 1924-August 1944).

Why We Wrote This

Political extremism can feel like a long-ago problem, even as incidents of violence make the headlines. History reminds us of how easily democracies can slip into fascism – and how they might resist the pull today.

Chaix had been a French resistance fighter, sparring against Nazi Germany and France’s collaborationist Vichy regime during World War II. He died at age 20.

That was enough to spark Le Tellier’s interest, setting him on a quest to learn about, and tell, Chaix’s story in “The Name on the Wall.” Le Tellier dug into archives and questioned townspeople. He learned that Chaix was one of the 13,679 members of the French Forces of the Interior (FFI) killed during the war. His father was a baker, and he had a brother who was four years his junior. Simone, his fiancée, was the center of his universe, to whom he wrote epic love letters on the backs of black-and-white photographs.

But Le Tellier does not exploit Chaix’s personal details in a glib attempt to help readers connect with his story, or the war. Instead, he draws from the myriad ways history has been influenced by unknown foot soldiers like Chaix – and ways in which it risks repeating itself.

“A point to remember,” he writes. “Fascist regimes operate faster than any democracy.”

At a time when Marine Le Pen’s far-right National Rally – formerly called the National Front – is making gains in France, Le Tellier reminds us that several of the party’s founders were supporters of the Nazi regime.

Pierre Bousquet was a former section leader of the Waffen-SS Charlemagne Division. The party’s first secretary, Victor Barthélemy, backed up police during the roundup of Jews at the Vél d’Hiv in Paris in July 1942.

Le Tellier also explores the notion that Nazism is a state of mind that is easier to slip into than any of us might like to think.

He recounts the story of a history teacher in Palo Alto, California, in April 1967, who re-created Nazi Germany in his classroom to teach students about the Third Reich. Similarly to American teacher Jane Elliott’s “Blue eyes/Brown eyes” experiment in 1968 to teach about discrimination, Ron Jones incited some of his students to join an invented “Third Wave” movement, while others were segregated and excluded. In the space of just one week, Jones managed to get “Third Wave” adherents to rat out others, with students coming close “to exchanging blows.”

Le Tellier issues a dire warning: There are dangers and risks for societies seduced by extremism, he says. “There is no debating such ideas, there can be no polite war of words. … Because democracy is a conversation between civilized people; tolerance comes to an end with intolerance.”

“The Name on the Wall” is a tidy, unassuming read, showing no signs of the self-importance that one could expect from an author whose “Anomaly” won France’s prestigious Goncourt Prize in 2020. Instead, the new book manages to straddle both historical nonfiction and personal narrative, without being preachy or predictable.

At times, readers may tire of Le Tellier’s frequent cultural references and name-

dropping, which are sprinkled throughout the short chapters. Readers who are not French (and many who are) may not understand the reference to “Pantagruel,” a ribald, satirical novel published by French writer François Rabelais in 1532.

But the best moments come when Le Tellier draws parallels between Chaix’s life and his own. In one poignant chapter, Le Tellier describes the loss of his ex-fiancée, Piette, to suicide when she was 20 years old – the same age Chaix was when he died, leaving behind his beloved Simone.

Le Tellier’s earnest look at Chaix – an otherwise unremarked-upon and forgotten character – allows readers to connect with a moment in history that continues to shape us all, whether or not we are aware of it.

“Without André Chaix as my plumb line, I wouldn’t have known how to explore an age when generosity and courage lived so unusually side by side with selfishness and despicable behavior,” writes Le Tellier.