This article is taken from the August-September 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

Six of the greatest works of modern literature were repeatedly and humiliatingly rejected by publishers and their distinguished advisors, who were blind to their merits.

André Gide considered Marcel Proust’s À la Recherche du temps perdu (1913–27) too snobbish, too slow and too long. T. S. Eliot thought George Orwell’s Animal Farm (1945) was too anti-Russian to be published during the war. Anne Frank’s Diary (1947) was too grim and too sad. William Golding’s Lord of the Flies (1954) was too violent and too cruel. Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita (1955) was paedophilic and pornographic.

The Sicilian novelist Elio Vittorini judged Giuseppe Tomasi di Lampedusa’s The Leopard (1963) to be old-fashioned and reactionary. During this literary Calvary two of these works were published posthumously. Anne Frank died of typhus in a concentration camp before her Diary was discovered. Lampedusa died before his masterpiece was recognised. All these works became enormously popular and were made into successful films.

1

Proust’s excellent biographer, George Painter, writes that the badly-typed À la recherche du temps perdu was first rejected by Calmette. They “refused to publish the two separate volumes of the work simultaneously, insisted on omissions and would not let anything interfere with the action!”

Proust then tried the prestigious literary magazine the Nouvelle Revue Française, which mainly published books by their own contributors and had two homosexual directors: André Gide and Jean Schlumberger. In 1911 Proust warned them that his novel was “extremely indecent; and part of the second volume would be a study of homosexuality”.

He added defensively that the Baron de Charlus is a “virile pederast, in love with virility, loathing effeminate young men, just as a man who has suffered through women becomes a misogynist. All the same, the old gentleman seduces a male concierge and keeps a pianist”.

The NRF rejected both the novel and the extract Proust had offered for the magazine. They politely said they had “read it with sustained interest” but had scarcely read it at all. Gide, who’d met Proust in fashionable salons 20 years before, condemned him as a social-climbing “snob, a literary amateur, the worst possible thing for our magazine”.

He thought Proust had condemned his own book by offering to pay for publication, found the early description of Tante Léonie’s bedroom distasteful and read no further. Schlumberger added that the 1,400-page novel was clearly impossible. Gide, later repentant and embarrassed about his rejection of Proust, confessed that he “had done no more than ‘scan’ — with a hostile eye — a few pages of the Temps perdu”.

A third publisher, Hamblot, candidly replied, “I may perhaps be dead from the neck up, but rack my brains as I may I can’t see why a chap should need thirty pages to describe how he turns over in bed before going to sleep.” Finally, the intelligent and energetic young publisher Bernard Grasset agreed to publish the novel at the expense of the author, who also paid for publicity. The first edition of 1,200 copies was priced at 3.50 francs, on which Proust received a royalty of 1.50 francs per copy. Painter wittily comments, “The words ‘author’s expense’, which had so deeply shocked the NRF, had acted on Grasset like a magic spell.”

2

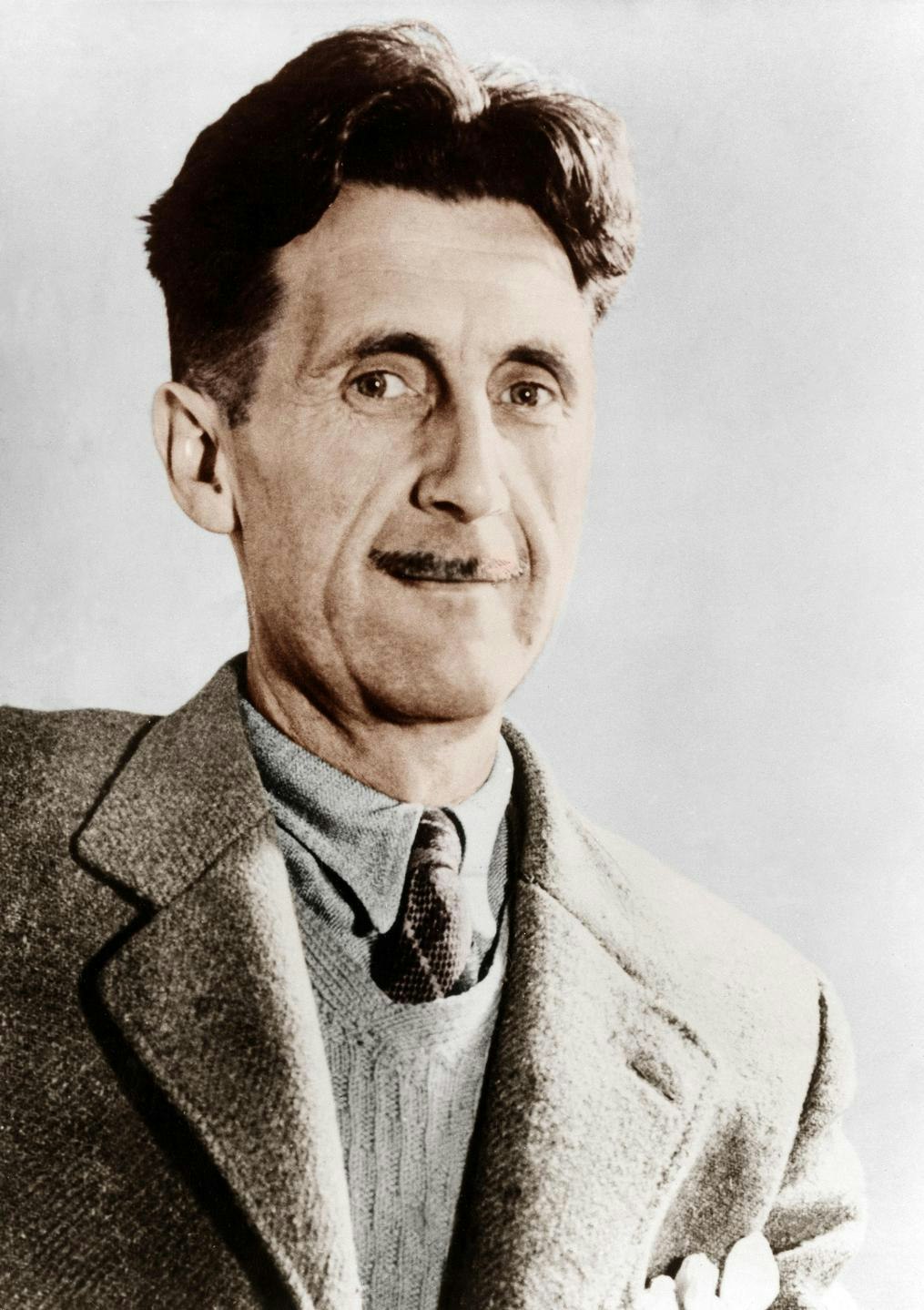

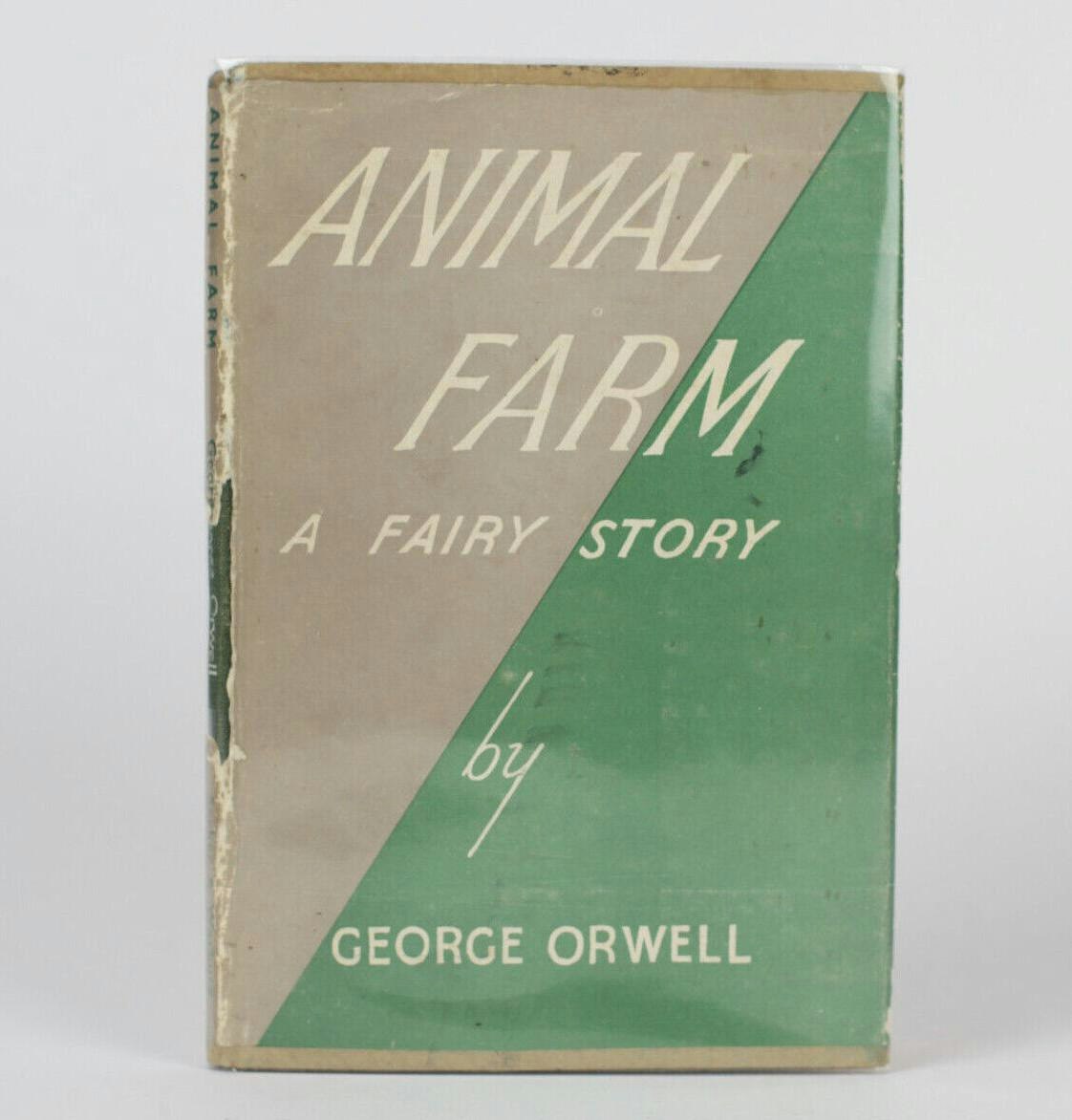

Orwell completed Animal Farm in February 1944, after the battle of Stalingrad when there was a strong feeling of solidarity with the Russians and before the landings at Normandy when the Allies first became victorious. He knew that his communist publisher Victor Gollancz would for political reasons never publish the book.

But Gollancz, enforcing his option on Orwell’s next work of fiction, insisted on reading it. As Orwell predicted, Gollancz “felt immediately that to publish so savage an attack on Russia at a time when we were fighting for our existence side by side with her could not be justified”.

After a quick refusal for the same reason by Nicholson & Watson, Orwell’s agent Leonard Moore submitted it to Jonathan Cape. Their reader reported: “This is a kind of fable, entertaining in itself, and satirically enjoyable as a satire on the Soviets,” and recommended publication.

But Jonathan Cape had some doubts and submitted it to a senior official in the Ministry of Information, who also appealed to Cape’s patriotism and advised him not to disturb Britain’s relations with its Russian ally. Following this official pressure, Cape changed his mind and wrote to Moore that it was “highly ill-advised” to publish the book during the war and drew attention to the troublesome porkers: “It would be less offensive if the predominant caste in the fable were not pigs. I think the choice of pigs as the ruling caste will no doubt give offence to many people and particularly to anyone who is a bit touchy, as undoubtedly the Russians are.” The book was also refused by William Collins, “the meanest of Glasgow Scots”, who cared nothing about the political aspects but didn’t think he could sell so short a book.

The typescript then went to T. S. Eliot at Faber & Faber. Orwell had worked with Eliot at the wartime BBC, lunched with him a number of times, invited Eliot to dinner and asked him to stay the night to avoid the blackout and air raids. Eliot’s perverse misreading of the book led to a grave misjudgement:

We agree that it is a distinguished piece of writing; that the fable is very skilfully handled, and that the narrative keeps one’s interest on its own plane — and that is something very few authors have achieved since Gulliver. On the other hand, we have no conviction that this is the right point of view from which to criticise the political situation at the present time.

The pigs were once again a sticking point:

And after all your pigs are far more intellectual than the other animals, and therefore the best qualified to run the farm — in fact, there couldn’t have been an Animal Farm at all without them: so that what was needed (someone might argue), was not more communism but more public-spirited pigs.

Having been shot down by the communist Gollancz and the Tory Ministry of Information, the book was then refused by the conservative Eliot. Dial Press in New York missed the political point entirely and rejected the book since “it was impossible to sell animal stories in the USA”.

Orwell finally turned to Secker & Warburg — then a much smaller and less influential firm than the others — which had published Homage to Catalonia. They were very keen to get Animal Farm and brought it out on 17 August 1945, three days after the Japanese surrender. This book and Nineteen Eighty-Four put the firm on the map, and Warburg reaped all the benefits of Gollancz’s investment in Orwell’s earlier books.

3

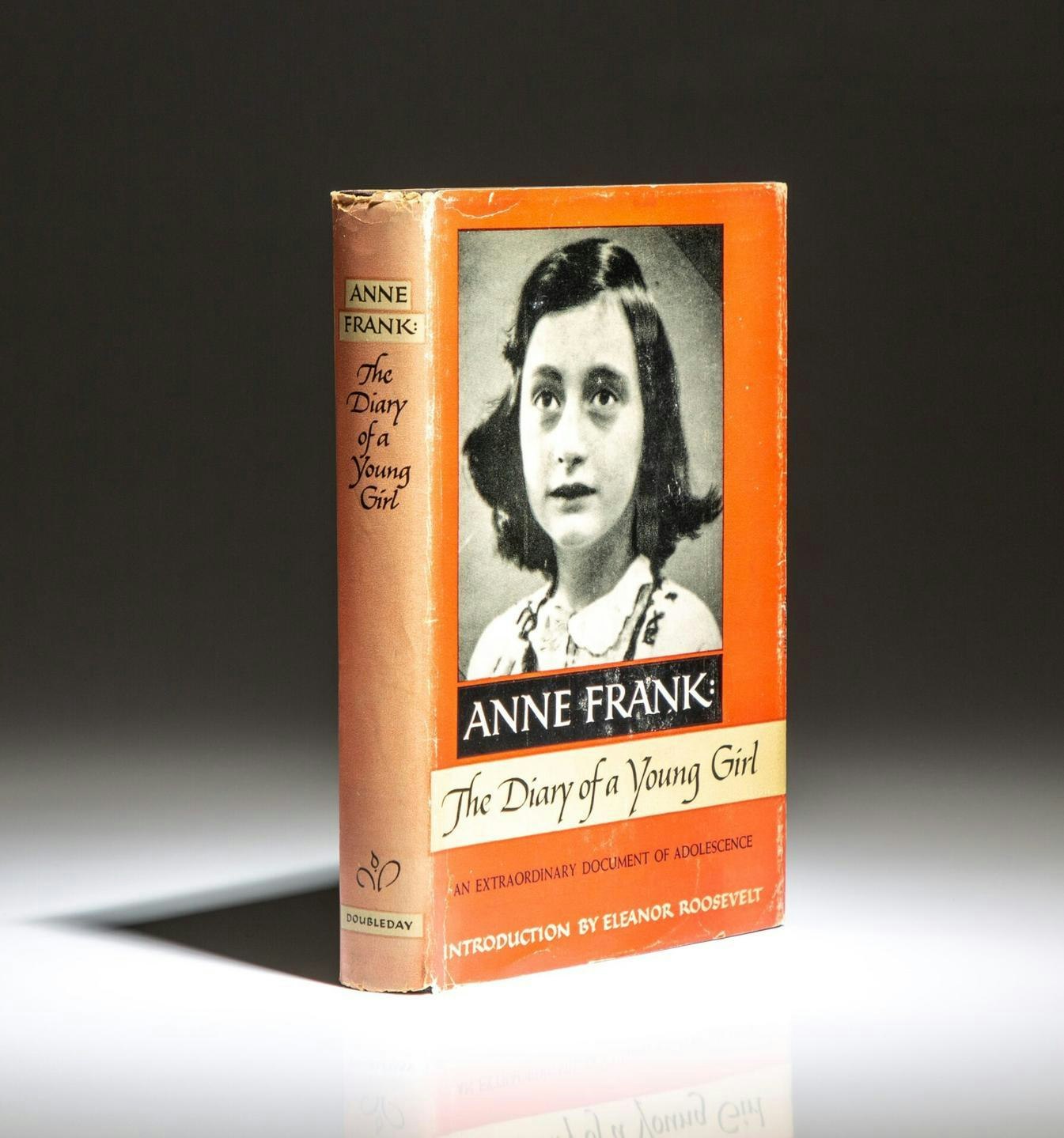

Anne Frank hid in the Secret Annex in Amsterdam from the age of 13 to 15, July l942 to August 4, 1944, and her Diary ended three days before her arrest. Her father’s employee Miep Gies was “stunned by the mess the Dutch police had left behind. The floor of the Franks’ room was covered with notebooks and papers. Amongst them was a little red and green volume with a checkered cover: Anne’s diary”.

Miep rescued the manuscript and gave it to Anne’s father Otto, the only survivor of the family, when he returned from Auschwitz in June 1945. He edited and typed the Diary and paid a subsidy. The book was published by the Dutch firm Contact as Het Achterhuis (The House Behind) and appeared in a print run of 1,500 copies in June 1947.

The book was rejected by 16 English-language firms, including the adventurous Secker & Warburg, and most of the big-name publishers in Britain and America. The Dutch “scout” recalled, “I was well connected in those days, but all the publishers I approached rejected the book.”

Francine Prose noted several obtuse responses: “I do not believe there will be enough interest in the subject to make publication a profitable business”; “it was very dull, a dreary record of typical family bickering, petty annoyances and adolescent emotions”; “The English reading public would avert their eyes from so painful a story which would bring back to them all the evil events that occurred during the war.”

She concludes, “the book was viewed as being too narrowly focused, too domestic, too Jewish, too boring”.

It’s astonishing that even the most hard-hearted editors were not moved to tears by Anne’s charming photo, brilliant style and tragic fate.

Little, Brown expressed interest and Otto accepted their offer. But, sensitive about advertising and exploitation of her suffering, he disagreed with their ideas about production and promotion and never signed the contract. Valentine Mitchell in London paid a modest advance of £50, offered a 10 per cent royalty on initial sales and published it in an edition of 5,000 copies in May 1952.

In the US, Judith Jones of Doubleday, struck by the charming photo of Anne on the cover of the French edition, rescued it from the rejection pile. Doubleday was enthusiastic and decided “to play down the grim aspects of the story and stress the beauty, humor and insight of this sensitive adolescent”. They considered and discarded more suggestive alternate titles: The Secret Annex; Behind the Hidden Door; Beauty Out of the Night.

The Introduction, signed by Eleanor Roosevelt, was actually written by the Doubleday editor Barbara Zimmerman (later Barbara Epstein, an editor of the New York Review of Books). They paid Otto a $500 advance and ordered a small print run.

Meyer Levin’s enthusiastic review in the New York Times Book Review inspired great interest, and the first printing of 5,000 copies sold out in a few hours. The Diary was eventually translated into 70 languages; the Japanese edition alone sold five million copies and had sold 35 million by 2014.

4

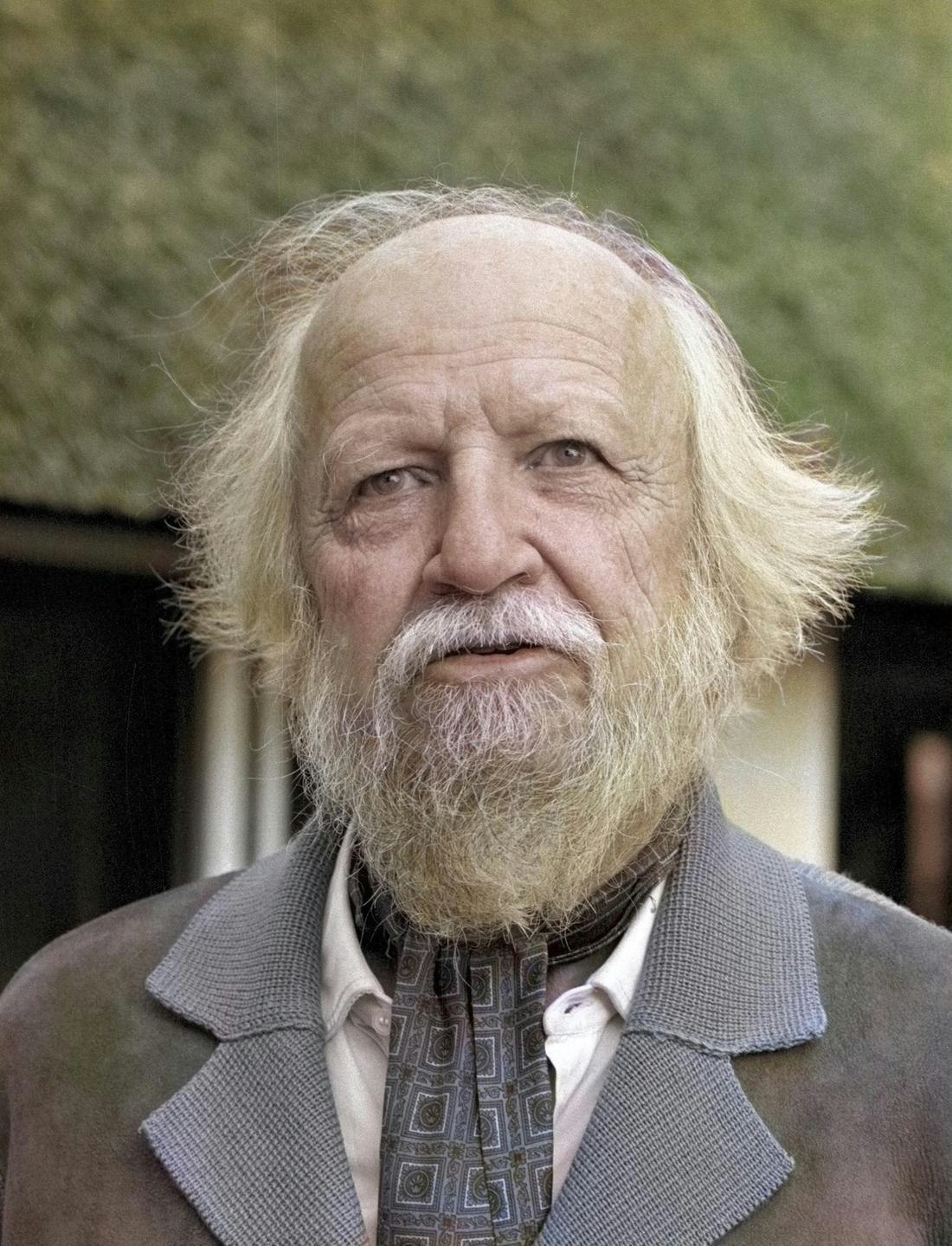

William Golding described his novel as an “unpleasant subject about a group of boys who get dumped on a desert island, and about the innate wound in human nature that makes them evolve into an unsatisfactory type of society”. Lord of the Flies, with the superior original title “Strangers From Within”, was rejected by Jonathan Cape after a typical wait of seven weeks. Cape replied, “It does not seem to us that you have been wholly successful in working out an admittedly promising idea.”

He was blindly followed by André Deutsch, Putnam, Chapman & Hall, Hutchinson, Bodley Head and the agent Curtis Brown. The original reader for Faber & Faber (there was no second Faber partner) foolishly reported: “Time: the Future. Absurd & uninteresting fantasy about the explosion of an atom bomb on the Colonies. A group of children who land in jungle-country near New Guinea. Rubbish & dull. Pointless.”

Charles Monteith, new to the firm and later elevated to chairman, picked the typescript off the rejection pile, got interested, met Golding and, writes Golding’s biographer John Carey, “saw at once that only a schoolmaster could know, so intimately, how awful boys could be”.

Monteith cut the preliminary chapters, sharpened the focus and tightened the structure. Golding gratefully replied, “I’m bound to agree with almost all your criticism and am full of enthusiasm and energy for the cleaning up process.” Faber asked for chapter headings to guide the readers, and offered an all-too-modest advance of £60.

The reviews — by luminaries such as George Painter (Proust’s biographer), Walter Allen, John Betjeman and E. M. Forster — “beautifully written, tragic and provocative” — were ecstatic. A friend told Eliot, a director of Faber, that his firm “had published an unpleasant novel about small boys behaving unspeakably on a desert island”. Eliot read it the next day and told Monteith that “it was not only a splendid novel but morally and theologically impeccable”.

5

Nabokov’s biographer Brian Boyd writes that Lolita (1955), which Nabokov called “a time bomb”, took two years to get published and another three to explode across America. James Laughlin, his avant-garde publisher at what Ezra Pound called Nude Erections, found it too risky and confessed, “it would be unthinkable to publish the book without destroying Nabokov’s reputation and his own”.

Nabokov’s best friend, the brilliant critic Edmund Wilson whose novel Memoirs of Hecate County (1946) had been banned and suppressed as obscene, reported, “I like it less than anything else of yours that I have read”. Viking, Simon and Schuster, Farrar Straus and Doubleday all felt they could not bring out the book without risking prosecution.

In his essay “On a Book Entitled Lolita” (1956), which argued that he was entitled to publish the book, Nabokov satirised the foolish rejections: “An otherwise intelligent reader who flipped through the first part described Lolita as ‘Old Europe debauching America’, whilst another flipper saw in it ‘Young America debauching old Europe’.”

Nabokov’s French agent then sent it to Maurice Girodias at Olympia Press. He published the serious but controversial Samuel Beckett, Lawrence Durrell, J. P. Donleavy and William Burroughs as well as Henry Miller’s Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn, which every American college student (like myself) smuggled home from Europe.

These authors were supported by income from the firm’s pornography, including The Story of O (1954), which Wilson admired. Boyd adds that “unlike every other publisher to whom Lolita had been offered, Girodias naturally was not daunted but positively enticed by warnings of the novel’s perverse sexual intensity”.

Nabokov — who argued bitterly with Girodias’ absurd demands and about his rights to American and British editions — explained his apparent naiveté: “I had not been in Europe since 1940, was not interested in pornographic books and thus knew nothing about the obscene novelettes which Mr. Girodias was hiring hacks to confect with his assistance.”

Relieved to get published, he could easily have discovered but chose to ignore the firm’s scandalous reputation. When he consulted his closest colleague at Cornell, Morris Bishop “thought the story of a man who loves little girls absolutely taboo in America. He found he could not read the novel through: Humbert seemed just too slimy”. Offended, Nabokov boldly replied: “It’s the best thing I ever wrote.” In June 1955 he signed the contract with Olympia Press, which made Lolita seem more pornographic than literary.

6

Lampedusa sent The Leopard to Mondadori in Milan in May 1956. His biographer David Gilmour explains that in December they replied with mealy-mouthed “intense regret” and rejected the novel with faint praise: “The book has interested us a lot and has had more than one reading. Nevertheless, the opinions of our advisors, though favourable, were not without reservations, and for that reason, bearing in mind our current burdensome commitments, we have come to the decision that it is not possible for us to publish the book.”

Mondadori’s main consultant was the Sicilian novelist Elio Vittorini, 12 years younger than Lampedusa. As a communist and neorealistic writer he was the antithesis of Lampedusa. He thought the text, “though worthy, lacked unity and completeness”, but actually condemned it as reactionary and regressive, an “untimely historical work without socio-critical relevance”.

When Lampedusa sent the novel to Einaudi in Milan, Vittorini stabbed him in the back again. He found the novel “very serious and honest”, but its tone and language were “rather old-fashioned”, and it was too “essayish and unbalanced”. Lampedusa died three weeks after receiving this sad news.

Feltrinelli’s reader, the Ferrarese novelist Giorgio Bassani, was impressed by The Leopard and wanted (too late) to discuss it with the author. “From the first page,” he declared, “I realised I had found myself before the work of a real writer. Reading further, I understood that this real writer was also a real poet.”

Feltrinelli in Milan published the novel in 1958, only six weeks after acceptance. But Lampedusa’s widow “signed an extremely disadvantageous contract lasting twenty years. The novel, which was about to become the first bestseller in Italian literary history, thus produced little material benefit to the author’s family”. Gilmour concludes that in July 1959, “The Leopard won … Italy’s leading award for fiction; by the following March, it had gone through fifty-two editions.”

Samuel Johnson explained such rejections by insensitive editors. When a woman asked him why he had mistakenly defined a horse’s pastern in his Dictionary, he replied: “Ignorance, madam, pure ignorance.” Worried about losing money on a controversial book, the editors lost a great fortune by failing to detect an unknown genius.