The Guardian’s Archie Bland is concerned about how mainstream the term “Boriswave” has become. It is, Bland says, a word coined and spread by the “extremely online right”. Sounds scary!

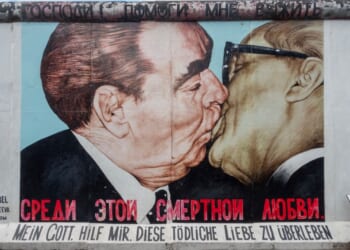

What concerns Bland about the term “Boriswave” as a means of describing the historically unprecedented rise in immigration under Prime Minister Boris Johnson’s government is that while the term is “often used as a neutral shorthand”, it “carries a charge”:

Think of the human specificity of the “Windrush generation” against the idea of a “wave” – an inhuman mass, entirely out of control.

Okay, I see his point. The term could potentially obscure the human distinctiveness of people in the “wave”. But against this somewhat negative framing, Brand presents a misleadingly positive rhetorical term — one that obscures a broad phenomenon with a specific reference, and a specific reference to an event that has been drowned by progressive myth-making. This is anything but a neutral alternative.

Commentators in the Guardian and the New Statesman like to huff and puff about how rhetorical terms and ideological concepts that have been developed in the group chats strange right-wing anons bubble up to the surface of mainstream discourse. Rhetorical terms and ideological concepts that Guardian and New Statesman commentators tend to be more favourable to, of course, have emerged organically and haven’t been spread through mainstream institutions by radical academics, partisan charities, obscure think tanks et cetera. To pick a random example, the term “global majority” was not created by a far left educationalist and then spread through ideologically captured institutions. People just started saying it.

This is what is so unconsciously dishonest about querulous commentary around the “extremely online right”. You don’t have to tell me that the “online right” contains a lot of unpleasant and off-putting people: people who would deport anyone who so much as had a tan; people who have such a beef with women that they seem to have more mummy issues than there have been issues of The Spectator; people with an eerily deep and passionate interest in the Latvian Legion of the Waffen-SS. Plus, as always in online circles, there are rampant egotists, outright sociopaths and sex-mad weirdos. I’m not ashamed to say it: I’m a woeful lib by the standards of a lot of the “online right” — someone who would not have seemed out of place by the political standards of a few decades ago.

But mainstream commentators lambasting extremism remind one of motes and beams. How was it not “extreme” to accept an annual intake of migrants almost the size of the population of Birmingham — just after voters firmly rejected two decades of mass migration? That this is seen as normal, sensible politics explains how many British voters have become more radical.

It is not surprising that people have been attracted to something more radical, and more incisive, and more funny

The “extremely online right”, meanwhile, has become more popular as a response to the abject uselessness of mainstream Conservatism. Again, it was a Tory government — not a Labour government — that explored new heights of radical liberalism on the national question. Right-leaning managerial commentators were musing complacently about how the issue of migration had been depoliticised. More rich-blooded right-leaning polemicists could only huff about the symptoms of the post-Blair world without addressing its condition, as well as employing the political genius that made them think that Kemi Badenoch would stun Keir Starmer into silence. It is not surprising that people have been attracted to something more radical, and more incisive, and more funny.

Online, we hear, are bubbles of radicalisation. Again, in case this is interpreted as a blanket apologia for the online right, you don’t have to tell me how delusional it is for people to think that a country where almost everyone has some amount of friendly contact with members of ethnic minorities will become an all-white ethnostate, or that a country where even being a mild-mannered Anglican can mark one out as a bit of an eccentric will become a bastion of Catholic traditionalism. But mainstream commentators have been “extremely online” as well — not as colourfully and aggressively, perhaps, but extremely so nonetheless. They used to congregate on Twitter, sharing restaurant recommendations and debating the finer points of pronoun usage. The country being transformed beyond recognition was just politics as usual. Shame about Brexit but soon the grown-ups would be back in charge. Now, a lot of them have migrated to Bluesky — a progressive utopia where everyone agrees on 99.5 per cent of things and the 0.5 per cent is their favourite episode of Dr Who.

In this bubble of progressive whimsy, it was easy to forget that fewer people were watching TV, and fewer people were listening to the radio, and fewer people were reading newspapers and magazines. Traditional means of influence were becoming less significant, in other words, even as citizens were becoming, justifiably, more cynical about their interests being represented. Like it or not, we are all becoming extremely online. In the digital spaces to which many people have turned, there has certainly been room for left-wingers to profit from discontent (a Novara Media, for example, could rival The Guardian). But there has also been space for right-wing anons to prove themselves to be better informed and more stylistically fresh than their stodgy onymous counterparts. People who dislike their growing influence will have to be more funny, more clever and more in touch with popular concerns.