This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

The death of music criticism, long foretold, came a whole lot closer this summer. One day in mid-July, the New York Times sacked both of its chief music critics, pop and classical, along with chief theatre critic Jesse Green and Margaret Lyons, who covered TV.

The reason given for their “reassignment” was more alarming than the bloodbath itself. A memo from the culture editor, Sia Michel, warned that “new generations of artists and audiences are bypassing traditional institutions” — the New York Times — whilst “smartphones have Balkanised fandoms”. What readers crave, Michel feels, are “trusted guides to help them make sense of this complicated landscape”.

In plain English, what the Times is looking for is music critics who are as different as possible from the expert, well-dressed, wisecracking reviewers who delivered first-night juice (wisecrack intended*) daily at breakfast. Those dodos have had their daybreak.

They include Times pop critic Jon Pareles who covered five decades of mass taste from “Rhinestone Cowboy” to Taylor Swift. No one knows more American tunes; he’ll probably be replaced by an app.

The classical critic, Zach Woolfe, just three years on the beat, was more fanboy than Frantz Fanon but he could be incisive, and he gave readers a good sense of being there. Woolfe, 40, has been dumped on the obits desk. Sic transit to oblivion.

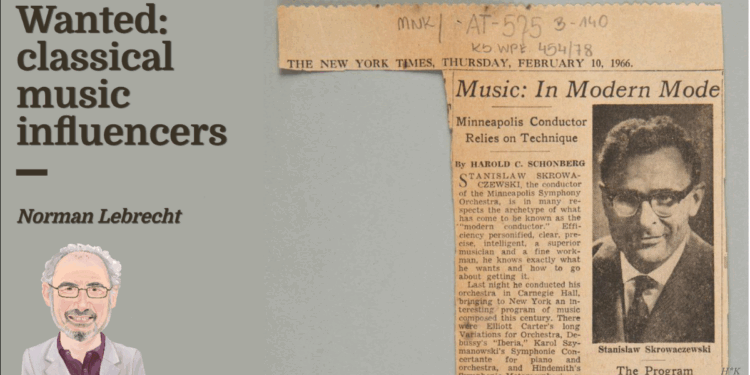

Why does this matter? Because a hostile New York Times review is worth more than a rave in ten other papers. Readers trust it, and artists use it to test their blood pressure. It has been over half a century since the Times last had a firebrand music critic in Harold Schonberg, who famously wrote: “Last night at Carnegie Hall, Jack Benny played Mendelssohn. Mendelssohn lost.” Schonberg earned the undying enmity of Leonard Bernstein, but New York devoured his every word.

He was a mentor to my generation, a chess master and brilliant pianist who never held back. None of his Times successors ever dared to be so bold, or maybe it is the times that changed.

Criticism, you see, is a fragile art. Like conducting, it is largely a confidence trick. If musicians see more in a baton than an aerial wave, the wielder will grow six inches taller. If a critic produces a “Verdi on Viagra” verdict, he or she will start to believe their own myth.

The reverse is also true. Conductors can be deflated by sourpuss cellos and critics by a down-page slot. Their self-belief rests on a convention of unsackability. Dismissals are rare in the extreme. A conductor is fired only for sex, a reviewer not even for that. So when four chief critics are blown away in one afternoon, it’s no small earthquake and a shaft of aftershocks ensued.

Vanity Fair and the Chicago Tribune swiftly abolished film reviews. The New Yorker axed an art critic. Here, the Observer shrunk its classical music review to a corner of a features page. The Sunday Times abolished music criticism altogether a year ago. The dailies have given up overnight reviews. People used to say, “I don’t go to many concerts but I keep up by reading the reviews.” No more.

Just this month, another blow landed. The Rubin Institute for Music Criticism, the world’s only such training programme, was suspended. The course, at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music, not only taught students how to write reviews. It actually paid their salaries to work as interns for a year or two at major newspapers such as the Boston Globe. They were starting to make headlines.

Sadly, the death of founder Steve Rubin and a “shift in philanthropic strategy” by the Getty Foundation means the fledgling critics will not be paid after this month, and the faculty will not convene again. Efforts are being made to save scraps from the rubble, but I’m not hopeful.

Where that leaves music criticism is in limbo — or, rather, on the internet, where a welter of well-intentioned sites publish notices by mostly unpaid reviewers. Their readership is uncertain, their influence marginal. Read on a telephone screen, a 400-word deconstruction of a night at the Philharmonic loses something in transmission. Words fail. The most widely watched web-crit is a paunchy New Yorker who bellows prejudices on YouTube about his most-hated recordings.

What hope, then, for criticism?

It’s worth remembering that the métier originated in London coffeehouses where Joseph Addison founded the original version of the Spectator in 1711 with his friend Richard Steele, who launched the rival Tatler. Both reviewed arts as a relief from politics. The Spectator continues and thrives, sharing a news shelf with The Critic, the Times Literary Supplement and other periodicals that cling to Enlightenment values of strong opinion and vigorous debate. They are the measure by which our civilisation will be assessed, if at all.

The New York Times, for its part, is looking for something else altogether. In its advertisement for a staff music critic it specifies: “You are a dynamic, digital-first writer who can conceive of multimedia-first criticism. You can write engaging essays, notebooks and reviews and are also eager to embrace strong visual, audio and video components in your stories.” Words come last. The salary, by the way, is $125–170,000, barely enough to rent a bedsit in the Bronx.

I remember Harold Schonberg paying for our lunch with an Amex corporate gold card. A critic’s credit has now been cut to shreds. Harold used to say: “Anyone who gets away with something will come back to get away with a little bit more.” He was usually right, in the long term.

*jus primae noctis