No doubt many of you cried near the end of the movie Awakenings.

The movie, based on Oliver Sacks’ bestselling book of the same name, struck an emotional chord with many people for the same reason that Flowers for Algernon did, and it turns out to be about as based on real life as that depressing work was.

“In his journal, Sacks wrote that ‘a sense of hideous criminality remains (psychologically) attached’ to his work: he had given his patients ‘powers (starting with powers of speech) which they do not have.’ Some details, he recognized, were ‘pure fabrications.’

— Steven Pinker (@sapinker) December 12, 2025

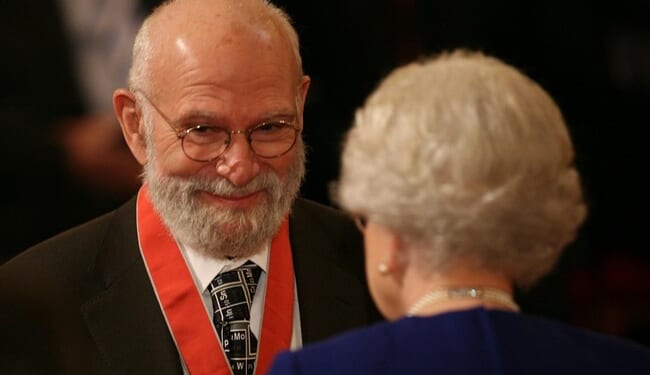

Sacks, who is among the most celebrated and influential medical practitioners and nonfiction authors in the world—he wrote 18 books, including two autobiographies—and Awakenings has been listed as a top-20 most important nonfiction work in history. He is also famous for his work, The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, which you have probably also heard of.

Oliver Sacks, M.D,. FRCP, was a physician, a best-selling author, and a professor of neurology at the NYU School of Medicine. The New York Times has referred to him as “the poet laureate of medicine.”

As an author, he is best known for his collections of neurological case histories, including The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat, Musicophilia: Tales of Music and the Brain and An Anthropologist on Mars. Awakenings, his book about a group of patients who had survived the great encephalitis lethargica epidemic of the early twentieth century, inspired the 1990 Academy Award-nominated feature film starring Robert De Niro and Robin Williams.

Dr. Sacks was a frequent contributor to the New Yorker and the New York Review of Books.

His work changed medical school curricula, influenced treatment strategies for patients with neurological disorders, and filtered into popular culture in innumerable ways.

He was also a fraud. It turns out that all his works were some variety of autobiography, in which he described aspects of his own personality, quirks, loves, hates, torments, and flights of fancy through the false biographies of his patients.

Much of his life, apparently, revolved around his personal torment that derived from his shame over being a homosexual, having grown up in England at a time when it was especially frowned upon, including by his mother, who told him she wished he had never been born. In fact, his career ended over accusations that he sexually abused patients—an accusation he vigorously denied.

Sacks’ fame is based on his ability to tell stories, and he certainly told compelling ones that captivated generations of people. While his colleagues were deeply skeptical of him, the general public and, eventually, the elite who fund and set curricula for medical schools were quite impressed.

Consider the main character in Awakenings, Leonard. He is portrayed in the most sympathetic way possible, and the movie is as much a love story as a tale of medical success and ultimate tragedy.

In reality, Leonard was not the poet we were told, but a man who looked fondly back on his youth as a rapist.

In the preface to “Awakenings,” Sacks acknowledges that he changed circumstantial details to protect his patients’ privacy but preserved “what is important and essential—the real and full presence of the patients themselves.” Sacks characterizes Leonard as a solitary figure even before his illness: he was “continually buried in books, and had few or no friends, and indulged in none of the sexual, social, or other activities common to boys of his age.” But, in an autobiography that Leonard wrote after taking L-dopa, he never mentions reading or writing or being alone in those years. In fact, he notes that he spent all his time with his two best friends—“We were inseparable,” he writes. He also recalls raping several people. “We placed our cousin over a chair, pulled down her pants and inserted our penises into the crack,” he writes on the third page, in the tone of an aging man reminiscing on better days. By page 10, he is describing how, when he babysat two girls, he made one of them strip and then “leaped on her. I tossed her on her belly and pulled out my penis and placed it between her buttocks and started to screw her.”

In “Awakenings,” Sacks has cleansed his patient’s history of sexuality. He depicts him as a man of “most unusual intelligence, cultivation, and sophistication”—the “ ‘ideal’ patient.” L-dopa may have made Leonard remember his childhood in a heightened sexual register—his niece and nephew, who visited him at the hospital until his death, in 1981, told me that the drug had made him very sexual. But they said that he had been a normal child and adolescent, not a recluse who renounced human entanglement for a life of the mind.

All of Sacks’ characters were fictionalizations of himself, or rather, some aspect of himself. He put his own words in their mouths, inserted his personal history into their lives, and privately referred to The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat as a “fairy tale.”

In a spontaneous creative burst lasting three weeks, Sacks wrote twenty-four essays about his work at Bronx State which he believed had the “beauty, the intensity, of Revelation . . . as if I was coming to know, once again, what I knew as a child, that sense of Dearness and Trust I had lost for so long.” But in the ward he sensed a “dreadful silent tension.” His colleagues didn’t understand the attention he was lavishing on his patients—he got a piano and a Ping-Pong table for them and took one patient to the botanical garden. Their suspicion, he wrote in his journal, “centred on the unbearability of my uncategorizability.” As a middle-aged man living alone—he had a huge beard and dressed eccentrically, sometimes wearing a black leather shirt—Sacks was particularly vulnerable to baseless innuendo. In April, 1974, he was fired. There had been rumors that he was molesting some of the boys.

Baseless? Perhaps. But perhaps not. The man was obsessed with his sexuality, deeply invested in his fantasy life, and every story he told in his “nonfiction” works turns out to be a fraud. I wouldn’t be so sure.

Sacks’s early case studies also tended to revolve around secrets, but wonderful ones. Through his care, his patients realized that they had hidden gifts—for music, painting, writing—that could restore to them a sense of wholeness. The critic Anatole Broyard, recounting his cancer treatment in the Times Magazine in 1990, wrote that he longed for a charismatic, passionate physician, skilled in “empathetic witnessing.” In short, he wrote, a doctor who “would resemble Oliver Sacks.” He added, “He would see the genius of my illness.”

It speaks to the power of the fantasy of the magical healer that readers and publishers accepted Sacks’s stories as literal truth. In a letter to one of his three brothers, Marcus, Sacks enclosed a copy of “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” which was published in 1985, calling it a book of “fairy tales.” He explained that “these odd Narratives—half-report, half-imagined, half-science, half-fable, but with a fidelity of their own—are what I do, basically, to keep MY demons of boredom and loneliness and despair away.” He added that Marcus would likely call them “confabulations”—a phenomenon Sacks explores in a chapter about a patient who could retain memories for only a few seconds and must “make meaning, in a desperate way, continually inventing, throwing bridges of meaning over abysses,” but the “bridges, the patches, for all their brilliance . . . cannot do service for reality.”

Sacks was startled by the success of the book, which he had dedicated to Shengold, “my own mentor and physician.” It became an international best-seller, routinely assigned in medical schools. Sacks wrote in his journal,

He pondered the phrase “art is the lie that tells the truth,” often attributed to Picasso, but he seemed unconvinced. “I think I have to thrash this out with Shengold—it is killing me, soul-killing me,” he wrote. “My ‘cast of characters’ (for this is what they become) take on an almost Dickensian quality.”

It is striking, as Steven Pinker notes, that The New Yorker seems unbothered by Sacks’ fabulism, or even entranced by the literary quality of his work. This essay was itself quite literary and focused as much on Sacks’ journey through psychoanalysis and self-discovery as on the fact that he was a fraud who fooled the world into believing “fairy tales” were science.

The New Yorker prides itself on rigorous fact-checking, but as with Sacks, it seems that facts matter less than narrative truth. Hence, they apparently allowed Sacks, a frequent contributor, to escape their “rigorous” process.

Because their primary commitment is to a belletristic, literarist, romantic promotion of elite cultural sensibilities over the tough-minded analyses of philistine scientists and technologists, their rival elite (carrying on C. P. Snow’s war of prestige between “the two…

— Steven Pinker (@sapinker) December 12, 2025

Because their primary commitment is to a belletristic, literarist, romantic promotion of elite cultural sensibilities over the tough-minded analyses of philistine scientists and technologists, their rival elite (carrying on C. P. Snow’s war of prestige between “the two cultures). A common denominator behind Sacks’s fabrications was that ineffable, refined intuition can surmount cerebral analysis, which is limited and cramped. It’s a theme that runs through some of their other blunders…

It is the STORY that matters, not reality. Viewed properly, Sacks’ work might be considered non-fiction still, since it reveals the inner person of Oliver Sacks.

Uh, no. Sacks was a liar. A fraud.

It pains me to say so, since many of his stories are fascinating and touching, but human beings need to be grounded in reality before they climb out of it and build something truly beautiful.

Oliver Sacks’ popularity stems from the fraudulent, and his authority stems from being a “scientist.” If he were an essayist who wrote fiction, he might be classified as a genius. As a man who derived his authority from science and a man who reshaped clinical practice, he is little different from the fraud who sent researchers down the wrong path to curing Alzheimer’s Disease by faking his “groundbreaking” research.

Fake science is one of the great plagues of our age. Yet, I suspect, the revelation that Sacks was a fraud will not tarnish his luster in the eyes of people who prefer stories and narratives to reality.

- Editor’s Note: Every single day, here at Hot Air, we will stand up and FIGHT, FIGHT, FIGHT against the radical left and deliver the conservative reporting our readers deserve. Sometimes, however, we just point and laugh, and let the radical Left embarrass itself. This is one of those times.

Help us continue to point, laugh, and expose the idiocy of progressive elites. Join Hot Air VIP and use promo code FIGHT to get 60% off your membership!