Presidents and lawmakers love and hate official numbers. When federal statistics show things are good, they point to the numbers with conviction. When the data’s not so rosy, they ignore it. And every once in a while, they cry foul.

It happened on Friday, when the Bureau of Labor Statistics revised sharply downward its previous job gains estimates, President Donald Trump called the numbers “rigged.” Then, he took what historians call the unprecedented step of firing Erika McEntarfer, the commissioner of the BLS, accusing her of faking the jobs numbers – without providing any evidence of data manipulation.

The president’s moves illustrate the rising clout of data in government decision-making and the reliance that consumers, investors and companies place on those numbers to make decisions.

Why We Wrote This

Donald Trump isn’t the first president to go to battle over official statistics. But firing his chief labor statistician raises questions. Trustworthy data, free from political interference, is vital for financial markets.

Until now, the credibility of government numbers – including the heralded BLS jobs report – has been so important to maintaining public confidence that most presidents have not interfered with the agencies that produce them.

In the rare cases in which they have, such as during the Nixon administration, they’ve taken steps to conceal it.

Mr. Trump’s abrupt firing of a government official – just hours after the release of unflattering economic data and before any investigation – represents a new and potentially harmful direction, historians suggest.

“This is about as fundamental as it could be in terms of the overall impact on the economy, the administration’s credibility, and the level of political interference in the bureaucracy,” says Donald Kettl, a professor emeritus at the University of Maryland and author of “Politics of the Administrative Process.”

“This is, I think, even a bigger deal than in fact it seems right now,” he says.

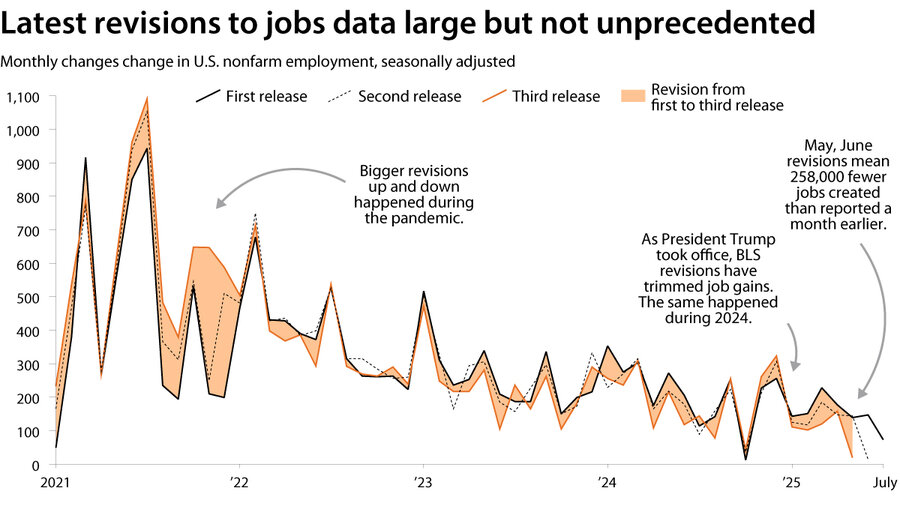

By any standard, the revisions in the July employment report for the previous two months were unusually large. In all, 258,000 jobs seemed to vanish (May’s new-job total plunged from 144,000 to 19,000. June’s went from 147,000 to 14,000.) And though those data reporting changes are big, they are not unprecedented.

An agency’s system and its critics

“The numbers were wrong and there has to be accountability for that,” Mick Mulvaney, the former head of the Office of Management and Budget and White House chief of staff in Mr. Trump’s first term, told CNBC Monday. Aside from the pandemic, the revisions were the largest since 1979, he added.

Critics say the BLS reports have been compromised by administrative job cuts at the agency and lower-than-usual response rates in its surveys. The president, in fact, eliminated a BLS technical committee that could have helped investigate why the revisions were so large.

Still, President Trump’s latest move is damaging in that it calls into question the credibility of future jobs numbers, according to researchers who have studied the federal statistical process.

“There’s a clear impression of political pressure, that the numbers need to come out a particular way,” says Tom Stapleford, a historian at Notre Dame and author of “The Cost of Living in America: A Political History of Economic Statistics, 1880-2000.”

Here’s how it happens: At the beginning of every month, the BLS puts out an employment report for the previous month. That report contains two surveys. One is of households, in which people reveal their employment situation and whether they’re looking for work. From this comes the unemployment rate.

The second is a survey of businesses and their payrolls. This generates the job-creation numbers, which are closely watched and considered a gold standard for employment reporting. It provides perhaps the closest thing to a real-time gauge of economic activity among federal statistical releases.

But the BLS jobs report has challenges. It makes assumptions that some statisticians disagree with. And many companies can’t get their current payroll data in by the deadline. Mr. Stapleford estimates that between 55% and 75% of companies polled make the deadline. After a month goes by, up to 90% have responded (resulting in a revision of the data). Then, a month later, the rest have trickled in (a second revision).

Another problem for the BLS report’s accuracy is seasonal adjustments. For example, when young adults get out of school for the summer and are looking for summer jobs, they’re considered “unemployed.” By the fall and into the end of the year, employment surges as people take jobs to help out retailers and delivery companies for the holiday shopping season.

If government statisticians didn’t make seasonal adjustments, employment figures would swing widely month to month. Because of the delays in data and seasonal adjustments, the BLS often revises the employment numbers of recent months.

Presumably, it’s last week’s revisions that most irked President Trump.

“In my opinion, today’s Jobs Numbers were RIGGED in order to make the Republicans, and ME, look bad,” he posted on Truth Social on Friday. “Just like when they had three great days around the 2024 Presidential Election, and then, those numbers were ‘taken away’ on November 15, 2024, right after the Election, when the Jobs Numbers were massively revised DOWNWARD.”

The BLS did revise downward previous job numbers around the turn of the year as Mr. Trump was taking office. What the president did not point out or complain about was that the bureau had done similar downward revising at the end of 2023, when his rival Joe Biden was in office.

The irony now is that the president could actually benefit from a bad jobs report if it convinces the Federal Reserve that the economy is slowing enough to warrant lowering interest rates. Mr. Trump has been pressuring the Fed to do so for months.

Other presidents have bristled over data

The episode illustrates the awkward dance that public officials perform when they get official statistics they don’t like.

Sometimes, they ignore the numbers. One famous example is the 1920 census, which showed a surge in urban populations in the Northeast, largely because of industrialization and immigration. A mainly conservative and rural Congress chose to skip reapportionment, the process of redistributing the number of representatives each state gets in the U.S. House of Representatives, for that decade, despite the constitutional requirement.

As a result, rural conservatives didn’t lose 11 seats to a Northern left-leaning and immigrant populace, according to a 2017 article by Kenneth Prewitt, former director of the U.S. Census Bureau.

Sometimes, politicians count in a different way. During the 1932 presidential campaign, in the depths of the Great Depression, President Herbert Hoover’s administration ignored the BLS figures and relied on another government report that showed higher employment levels.

Perhaps the closest parallel to Friday’s firing happened in 1971, after the BLS reported that unemployment that June had dropped from 6.2% to 5.6% – good news for President Richard Nixon, who faced reelection the next year.

When he read the following day that the bureau warned the drop might be “a statistical quirk,” he quietly reassigned the assistant BLS commissioner who had made the “quirk” comment, according to an account by Kenneth Hughes Jr., a historian at the Presidential Recordings Program at the University of Virginia’s Miller Center.

Later, Mr. Nixon considered secretly manipulating the numbers in minute increments, Mr. Hughes writes in an email. President Nixon “didn’t manage to corrupt the employment figures to serve himself politically, but Trump could. … That would be much worse for American businesses and employees and everyone who depends on accurate economic information from the government.”

Many researchers doubt that BLS statisticians will be influenced by Friday’s firing over the short term. But the Trump administration is working on reimplementing a presidential directive, known as Schedule F, that would allow the administration to reclassify many federal workers as at-will employees, rather than protected civil servants, making them more accountable to presidential wishes. That could soften bureaucratic resistance to his efforts, critics say, and make it easier to fire federal workers he disagrees with.

“The Trump administration … has made no secret about its desire to get rid of people who are trained in their jobs if they are not loyal to the current president,” says Stuart Shapiro, dean of the public policy school at Rutgers University and author of “Trump and the Bureaucrats: The Fate of Neutral Competence.”

“Schedule F will likely be put in place soon,” he adds. “And we will see another very dramatic example of that trend when that happens.”