Water was never something Genaro Acevedo Jiménez had to worry about in this verdant slice of rural Panama.

But now, water has become his biggest problem.

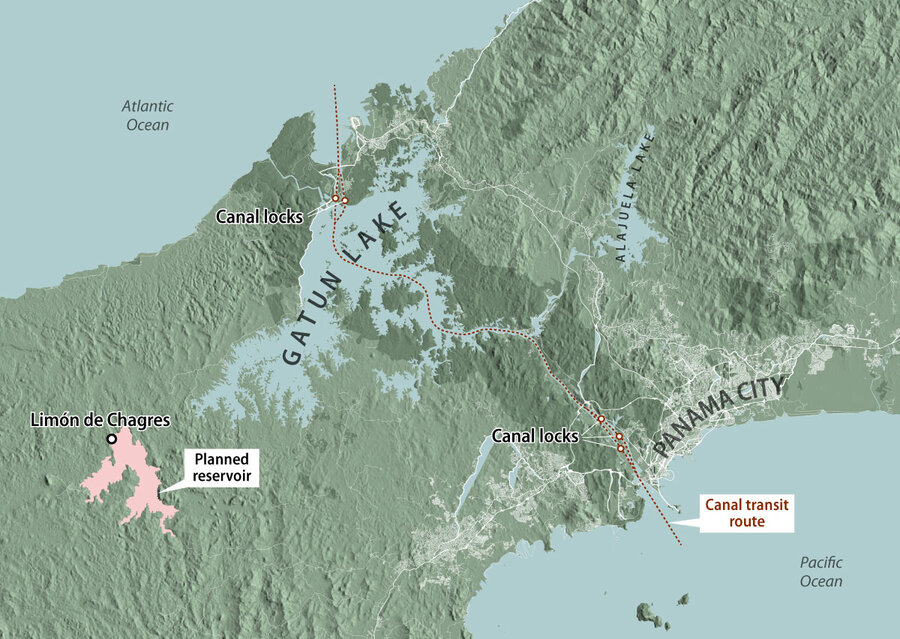

His village sits near the Panama Canal, on the site of a proposed dam and reservoir that authorities say are necessary to keep one of the world’s most critical trade routes passable.

Why We Wrote This

The Panama Canal was an engineering marvel when it was completed in 1914. But a modern effort to save the critical waterway amid water shortages could exact a high human toll.

“We can’t live underwater,” Mr. Acevedo says, sweeping his arms out toward the lush green hills and terra-cotta-red soil that he’s farmed for the past 43 years. “This is all we have.”

The Panama Canal, which connects the Pacific and Atlantic oceans, sees 5% of world trade – and 40% of all U.S. container traffic – pass through it. It’s so coveted that the U.S. has threatened to take it back, provoking a geopolitical war of words this year over ownership. So, following two historic droughts in less than a decade and growing population demands that have put the canal under pressure, the Panama Canal Board of Directors in March approved the Río Indio Dam that could wipe Limón de Chagres entirely off the map.

Mr. Acevedo’s concerns are more immediate than most, but he is not the only person to question the value of a large dam like this one. Across the world, many experts argue that most dams are simply not worth their social or environmental costs.

The Panama Canal is ground zero for the debate over where the right balance lies.

“In Panama there is a clear awareness that the canal is a national resource,” says Olga de Obaldía, executive director of the Foundation for the Development of Citizen Liberty, a Panamanian nongovernmental organization. What isn’t clear to the population, she says, is how much environmental or social damage is worth it to keep its water flowing.

Changing climate

It takes an estimated 50 million gallons of freshwater to move vessels through the Panama Canal’s locks system, which functions like a staircase. Boats rise through a set of locks, move across a lake, and then descend another set of locks as they pass between two oceans. That water has historically come from Gatun Lake, a reservoir whose construction in the early 20th century displaced several communities.

The Panama Canal Authority (ACP) is responsible for the management and conservation of water in the Panama Canal watershed, which spans roughly 3,400 square miles, or 6.5% of Panamanian territory. It also provides drinking water for some 55% of the population.

In 2005, when the canal was preparing for an expansion in width and depth, including a new traffic lane to accommodate larger vessels, the ACP created a master plan and concluded they could manage water challenges with solutions that didn’t involve community displacement. That meant steps like recycling water back into Gatun Lake to better withstand dry seasons.

But 10 years into what the ACP considered a 20-year plan, El Niño, a climate pattern known for warming the ocean’s surface, contributed to a historic drought. Then, in 2023, another severe drought created such low water levels that traffic through the Panama Canal fell by roughly 30%.

In 2024, a Panama Supreme Court decision paved the way for the ACP to alter the path of the water of the Río Indio Valley “for the sustainability of the canal and for the [national] population’s water access,” says John Langman, vice president of the Water Projects Office at the ACP.

The ACP decided on a dam, going against a global trend. Just a few years ago, environmentalists started asking if the world had hit “peak dam” – as the number of dams constructed annually fell from about 1,500 in the 1970s to roughly 50 a year by 2020. Many saw the decline as an explicit recognition of the social, environmental, and economic toll of these megaprojects.

“Dams have historically been designed and built based on the historic record of [river] flows and rainfall,” says Josh Klemm, co-director at International Rivers, a U.S.-based nonprofit. “But climate change has completely upended that.” And yet several large dam projects around the world have been funded in recent months. This one in Panama, he says, could end up creating high social costs with potentially low returns on water given a changing climate.

Disrupting lives

Limón de Chagres is home to almost 2,300 residents who depend on the Río Indio for fishing, bathing, and transportation. The town had no paved roads until three years ago. Most here board boats to get to the nearest hospital or shops. Residents are proud of what they’ve built on their own, like the community’s tiny cement church with a tin roof.

But they feel little connection to the Panama Canal, with its closest visitor center about 40 miles away. “I’m not proud of the canal,” says farmer Claudio Dominguez, who arrived 42 years ago, raising four children here. “Why feel pride about something that doesn’t benefit me?” he asks, horses whinnying beside him.

The ACP maintains its compensation model meets modern standards. Mr. Langman says packages for each family will depend on where they want to go next, how much land they own, and other variables determined through a detailed census.

“International requirements for this project are much more demanding than in 1935,” he says. That’s when the last displacement due to a canal reservoir project, Alajuela Lake, took place in Panama.

But, “There have been lessons learned from more recent projects” nationally and internationally, says Mr. Langman. His office has studied the effects of Panamanian hydroelectric dams, like one built by the government in 2011 that flooded towns, and the ACP has reached out to community defense groups to better understand what residents in places like Limón de Chagres may need in this delicate process.

Despite the effort, there are still high levels of mistrust. Many fear being displaced to cities. “We’ve been raised in the countryside,” says Elizabeth Rodríguez, whose two young sons hide behind her legs and play on the grass in front of the church on a blistering morning in March. “To change habitats would be difficult.”

“They [the ACP] haven’t been clear” on what comes next, she maintains. Many community members are refusing to meet with ACP representatives, blocking them from town or turning them away from their property. In neighboring Tres Hermanas, ACP representatives were chased out in late April.

Some 80 million people worldwide had been displaced by dams by the turn of this century. Although there have been great strides in how people are moved or compensated for dam projects, Mr. Klemm says “impoverishment is the rule, rather than the exception.”

That’s what scares Mr. Acevedo, the farmer, most. “I’m finishing my time on Earth,” he says, but to take this land and way of life away from local youth is to “kill them.”

He calls Limón de Chagres a gift from his ancestors. And that’s what makes wrapping his head around the dam situation so difficult: For the Panama Canal to have water, he has to give up the life he’s built and the community he cherishes.

“How can it be?” he asks.