This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

I find cocks’ heads unrewarding, though in Ávila, at the hour of the apéritif, men suck and crunch them whole — beaks, eyes, coxcombs — and spit out the bones with no pretence at decorum. Extremities of edible quadrupeds — ears, cheeks, ox tongues and tails, cow heels, trotters — are much more tempting and typically delicious, without offending sticklers for etiquette. They have the allure of diminishing accessibility: hard to sell in the Anglophone world and, therefore, hard to buy.

Even in lands where denizens appreciate offal, some arcane organs are becoming almost unobtainable. On an afternoon of slanting sun a few years ago, at a rickety table under the blank bulk of the cathedral of Palencia, the waiter proudly told me that criadillas were available.

“These are really yummy. What are they?” asked my wife, forking up her eighth or ninth mouthful. I waited until, with unfeigned enthusiasm, she had finished the platter, before I replied, “Bulls’ testicles.” She decided she hadn’t liked them after all.

The same problems of irrational fastidiousness and reduced availability apply equally to the innermost delicacies of similar creatures — especially in Indiana, where I spend half the year, longing, when winter comes, for a comforting bowl of tripe.

People who love loin will not eat liver or lungs. Gobblers of steaks gob over sweetbreads. In the United States, I suppose, these tender organs are wasted in cat food or dumped in reeking landfill.

The paradox is that the harder offal is to obtain, the more its scarcity value grows. I predict that tripe will follow the trajectory of oysters, transformed from the pabulum of plebs to rarities for the rich.

The market’s persistent indifference to the delights of tripe is due in part to horrible recipes. Cooked in the English manner with milk and crudely sliced onions, tripe is deservedly dismissed as disgusting.

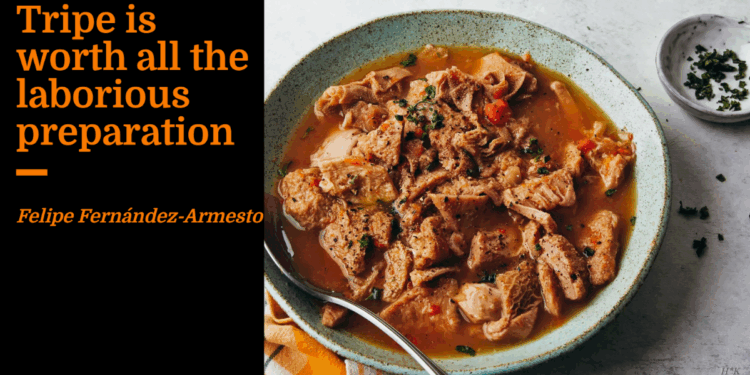

I eat it à la mode de Caen in Normandy, out of respect for local sensibilities, but find the sauce too thick and insufficiently piquant. Tripe-meat initially imparts soft, bland sensations, like a sagging, slumberous bed, and its flavours need awakening. Its unique texture — ribbed and honeycombed — is ideal for trapping a sauce of the right consistency.

Yet there’s no denying that tripe is trouble: it calls for scrupulous cleaning, laborious preparation and protracted cooking, whereas ears (if you can get them), liver, kidneys and sweetbreads of good quality need only simple grilling.

In an Indianian November, when gust-blown hail stings my cheeks and stiffens my bones, whilst slush seeps into my socks, I think the effort that tripe demands is worthwhilst, just for the warmth and solace it yields — if only I can get the stuff.

In Britain, the ingredients are still dispensed with only a little difficulty. Butchers, where they exist, will do the cleaning for clients. The cook’s goal is to ensure that the meats in the stewpot are tender but structured, whilst the sauce is slightly viscous but not dense or greasy.

A good four hours of simmering in water, for up to a kilo of tripe, will supply the former requirement. Vital for the latter is sparing use of the gelatinous concoction that ensues, with care to make sure that the added meats are lean.

Chorizo is traditional in Spain, but tends to exude too much fat. Instead, a good fistful of smoked paprika in the pot, with capers, bay leaves, lean chunks of ham, bacon and pastrami, and a pinch each of salt and cayenne pepper, imparts the right flavour.

Towards the end of the fourth hour, the sauce calls for a deep pan, where finely chopped onions and garlic are slowly rendered translucent in olive oil, seasoned with more paprika and pepper, and slightly caramelised with muscovado sugar.

Anyone who wants chorizo and black pudding should insert it, fairly finely sliced, at this stage, and drain off the fat before adding chopped tomatoes and peppers. Unstinted slugs of tomato purée, coarse wine and red vermouth follow.

The meats from the stewpot go in when the mixture starts to reduce. Spoonfuls of the stewed liquor, added a little at the time, adjust the consistency.

Starchy complements are essential: the crusty bread that stays on tables in Spain throughout every meal, and floury potatoes, boiled to slight softness — or chickpeas (which in my home region of Galicia are poached with the tripe but which can be cooked in advance and added with the tomatoes and peppers). “You are offal,” as the drag queen said to the chitterlings, “but I like you.”