A seminar at the University of Bristol by Professor Alice Sullivan, the UCL sociologist who led the government’s Independent Review of Data, Statistics and Research on Sex and Gender, was disrupted by a large and hostile protest, prompting police intervention and a change of venue.

Professor Sullivan had been invited to speak at the School of Policy Studies on 22 October, presenting findings from her government-commissioned inquiry into how sex and gender are recorded in official data and the barriers gender-critical researchers face when addressing these subjects, including difficulties obtaining research ethics approval, publishing work on sex-based differences, progressing their careers, and even, irony of ironies, holding events on university premises.

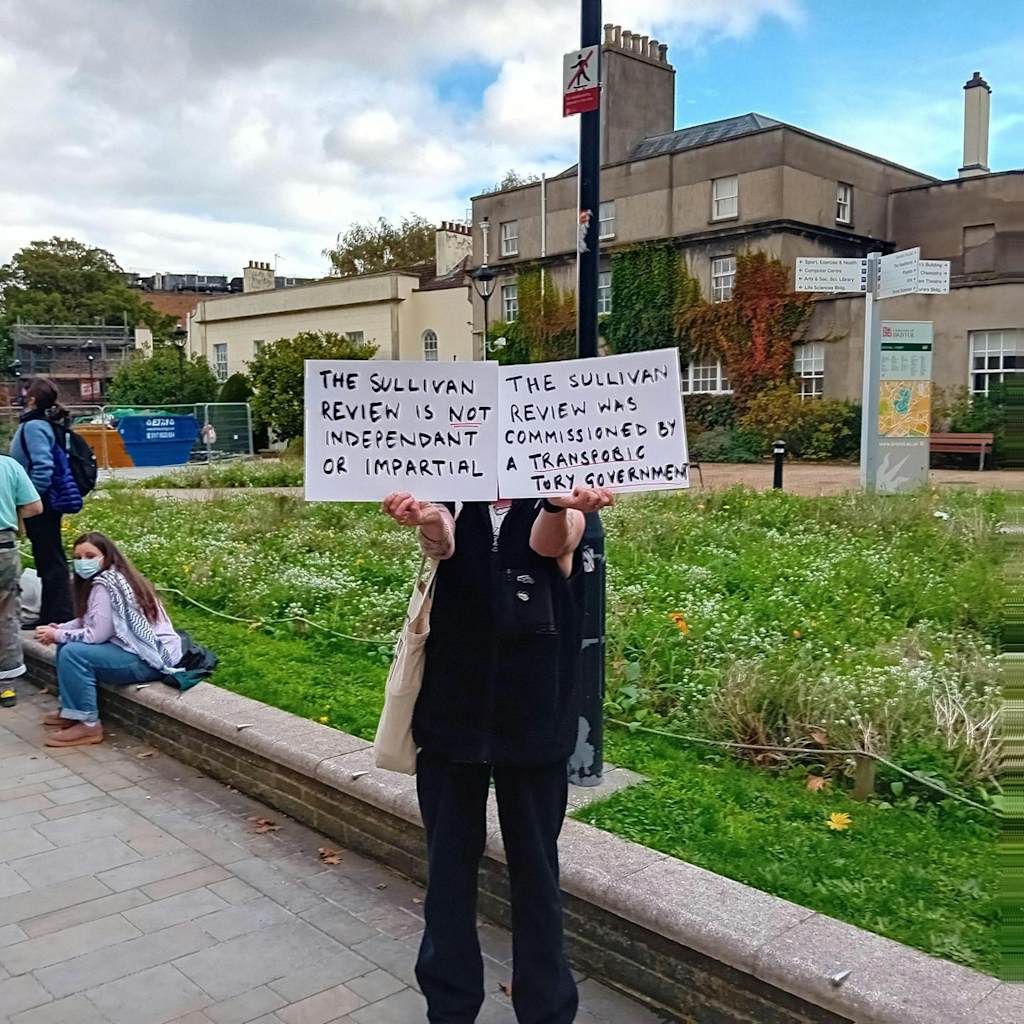

Outside the venue, demonstrators chanted and held placards accusing the review of being “transpobic” [sic] and — just as egregiously in their eyes — “commissioned by a Tory government”. Another read “No bigots in Bristol”, with its author, displaying the same free-wheeling, happy-go-lucky approach to English orthography as his or her barricade-dwelling comrades, adding, “Espesially [sic] ones who are funded by white supremacists.”

The protest escalated as the seminar began, with footage showing protesters using loudspeakers and chanting so loudly that Professor Sullivan’s voice was at times drowned out inside the lecture room. Others banged on windows, and a fire alarm was triggered mid-event. Mounted police and university security officers were eventually called to maintain order. Organisers were forced to move the seminar to a higher floor in the building so that it could continue.

It hardly needs saying that the scenes in Bristol reflect a broader and long-running dispute within academia over how sex and gender should be understood in research and public policy. Gender-critical scholars, including those interviewed for the Sullivan Review, point out that biological sex is an immutable, binary characteristic — male or female — and that conflating it with gender identity undermines the accuracy of data on issues such as health, crime and education.

Advocates of gender-identity theory, by contrast, claim gender is a spectrum and view binary classifications as socially constructed and exclusionary. For some trans activists, therefore, any defence of sex-based data is perceived as an existential threat to trans identities — a conviction that too often sparks hyperventilating displays of righteous anger, where allowing a gender-critical feminist to speak on campus is cast as an act of both real and symbolic violence, where every dissenting utterance becomes a wound to vulnerable gender confused children everywhere, where the clock’s already struck midnight and there’s no time — “None at all; none, do you hear, bigots! None!” — for the weary academic conventions of civility, tolerance or open debate.

Professor Sullivan is no stranger to such treatment. In 2020, when she was due to take part in a NatCen Social Research seminar on how Britain conducts its census, organisers withdrew her invitation after internal complaints from staff — including from Nancy Kelley, then deputy chief executive of NatCen and soon to become head of Stonewall — alleging that Sullivan held “anti-trans views”.

A similar episode occurred last year when she was invited to speak to Canada’s Department of Justice to mark International Women’s Day. The lecture, on the risks of prioritising self-declared gender identity over biological sex in official data, was cancelled shortly after she submitted her slides. A departmental official later intimated the event could not proceed and offered no formal explanation, though, as Sullivan later observed, “we both knew what the reason was”.

For all these experiences, however, Professor Sullivan described her time at Bristol as “a surreal moment”. Writing on X, she thanked the department and security team for ensuring the talk could proceed, but added that “the demonstration was apparently quite ugly, with mounted police needed. I have never experienced the like.”

Bristol’s decision to relocate the event and ensure it continued appears consistent with its duties under the Higher Education (Freedom of Speech) Act 2023, which strengthened universities’ obligations to uphold academic freedom. The Act imposes a positive duty to take “reasonably practicable steps” to secure freedom of speech within the law for staff, students and visiting speakers, including protecting academics’ freedom to “question and test received wisdom” and to express controversial or unpopular opinions without risk to their employment or privileges.

To support these duties, the Office for Students has issued detailed guidance on what counts as a “reasonably practicable step”. Paragraph 111 of this document states that while protest is itself a protected form of free expression, it cannot lawfully be permitted to prevent others from speaking — the so-called “heckler’s veto”. As the guidance explains, it will not be reasonably practicable for a university to allow “speech or protest that itself disrupts speaker events … for example by shouting at such volume and for such length of time that others cannot be heard or engage in teaching or discussion”.

By taking action to ensure the seminar could proceed, Bristol appears to have met its statutory obligations. Yet the scale of the disruption raises a wider question: can the law alone protect academic expression from intimidation? Without a broader cultural shift that restores an environment where competing views can be aired without harassment or disruption, the kind of behaviour that blurs the line between legitimate protest and the “heckler’s veto” is unlikely to diminish. Indeed, judging by the reaction among trans activists to the Supreme Court’s recent For Women Scotland ruling that under the Equality Act 2010 the terms “sex” and “woman” refer to biological sex, it may only intensify — “espesially” when, as the student protesters outside Professor Sullivan’s seminar would no doubt wish to remind us, “transpobes” bring their immutable biological bodies onto campus.