Within weeks of his marriage to his young bride Frances Shea in April 1965, Reggie Kray was taking out his anger on her during the sadistic and violent rages horribly familiar to anyone who crossed him and his twin Ronnie during their reign of terror in London’s East End.

One night, knowing how morbidly squeamish his 21-year-old wife was, he deliberately cut his own hand and bled all over her.

Such abuse was all too typical in a relationship dominated by the fear which left Frances in the throes of breakdown and drugs, and led to tragedy two years later.

Things started miserably on their honeymoon in Athens. Black-and-white photos taken at the Acropolis show an unhappy, uncomfortable couple, completely at odds with their surroundings – and with each other.

Most nights, Reggie went out drinking, often leaving Frances alone in their hotel and, according to the Krays’ business associate Micky Fawcett, failed to consummate the marriage. Fawcett recalled how, just after they returned from Greece, the newlyweds joined him for a drink at the Krays’ El Morocco club in Soho.

‘I’d hardly said “hello” before she said in front of him, “Do you know he hasn’t laid a finger on me in all the time we’ve been away?” Reggie himself didn’t sound angry, though, just defeated. “Cor, I’m glad it’s you she’s told,” he said sadly “and no one else.”’

Ten years older than his virginal bride, Reggie had been having covert sex with men since his teens. Even as he died in October 2000, his second wife Roberta and his long-term former boyfriend sat on either side of the bed.

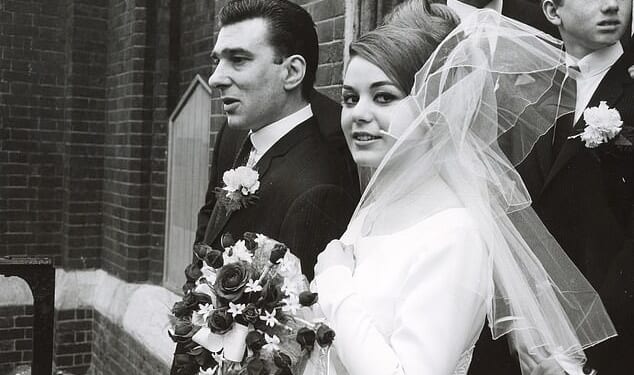

Frances Shea and Reggie Kray on their wedding day, in a photo taken by David Bailey

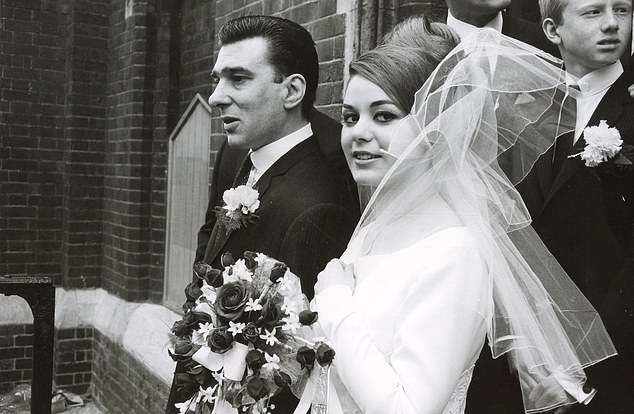

The couple outside their Bethnal Green home in east London

As I described in yesterday’s Mail, he had once tried to pounce on Frances’s older brother Frankie, who would later claim that Reggie only started dating his sister in revenge for Frankie rejecting his advances. Reggie had also had frequent one-night stands with women, usually nightclub hostesses and prostitutes, both before and probably during his courtship of Frances.

Yet, while he later confided in Micky Fawcett that he could have sex with these women, Frances was different. ‘He had a bit of a Madonna complex about her,’ Fawcett told me. ‘In his mind she was an idol, nothing to do with love between a man and a woman. Somehow he felt she shouldn’t indulge in sex.’

Whether Reggie could not consummate the marriage because he preferred men or because he simply could not bring himself to damage or defile Frances’s purity in any way remains an unanswered question.

What we do know is that he succeeded in defiling her mentally, totally destroying her peace of mind as they attempted to live as man and wife. He moved them into a flat below Ronnie’s in Cedra Court, a 1930s block in Clapton, East London. He could have chosen so many other places to live but Reggie wasn’t comfortable anywhere away from his twin.

He’d wanted Frances; he’d got her. Now there were three of them in the marriage, a terrified young wife, an intense, obsessive husband and a jealous madman who detested the sight of her and saw her as a threat to their twinship.

At Cedra Court, Reggie made considerable efforts to provide a comfortable home with new furniture and plush carpeting and Frances was pampered beyond reason. He’d buy her anything she wanted.

But he was so intensively possessive that she became virtually a prisoner. Sure, she could go shopping whenever she fancied, buy what she liked – as long as someone from the Firm accompanied her. And none of this could compensate for the living hell Frances was descending into, the twins’ erratic, booze-soaked, criminal way of life.

Reggie kept a loaded firearm by the side of their bed, along with an arsenal of other weapons including a chopper and a flick knife under his pillow.

On the nights when they stayed home at Cedra Court, Reggie would down his first gin of the evening, leave Frances to the telly and climb the stairs to Ronnie’s flat where he’d remain until the small hours. Once in bed, it would be impossible for Frances to nod off without a sleeping pill: the noise from the flat above, where Ronnie constantly partied and entertained his friends, was unbearable.

Attempting to question or remonstrate with her drunken husband when he finally returned made everything worse. On and on he’d go, ranting and raving, swearing and shouting, threatening to hurt her and kill her family, until, finally, the taunts would stop and he’d lie down and pass out.

It was at Cedra Court that he terrorised Frances by dripping his own blood on to her but that wasn’t the worst of it.

On one occasion, Ronnie brandished a sword at Frances, saying, ‘I’ll put this through you’, then started laughing, pretending it was a joke.

On another night, Reggie and Ronnie returned to Cedra Court where Ron’s bodyguard Billy Exley had been left behind to make sure that Frances didn’t leave the flat. While Ronnie retired with one of the many young men who were his sexual partners, Reggie and a ‘hostess’ he’d brought back went to the bedroom where Frances was out cold from the sleeping tablets the twins had made her take before they went out. Waking up in the morning, Frances was horrified to find that she had been an unwitting and unwilling participant in a bizarre three-in-a-bed with Reggie and the other woman but when she tried to get out of the room the door was locked. When she did finally get out, Billy Exley was forced to watch as Reggie slapped her to calm her down.

Eventually, Ron came into the room and grabbed her as she made a dash for it, taking her back into the bedroom where Exley heard him telling Reggie to stuff pills down her throat to keep her quiet.

Her diary records how, whenever Ronnie was around, Reggie talked to her ‘like a pig’, swearing at her and abusing her verbally, and frequently telling her to ‘shut your mouth’.

He was always arguing with her in front of his family at their home in Vallance Road and Ronnie was happy to join in. One night he started talking about girls writing letters to the twins, and how they were going to take them out, a speech aimed at tormenting her.

Already an anxious young woman even before she met Reggie, Frances became overwhelmed with fear and depression.

According to her diary, she had to ‘keep on’ at Reggie for what she called ‘tablet money’ – implying that she was already reliant on certain types of medication thanks to the debilitating emotional decline she experienced just weeks after their wedding.

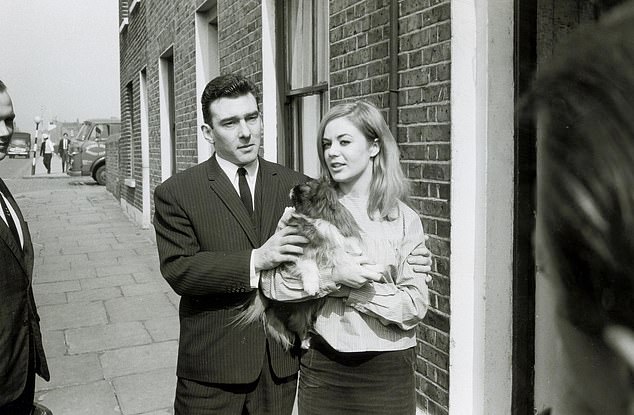

Ronnie (left) with Reggie and Frances at their wedding

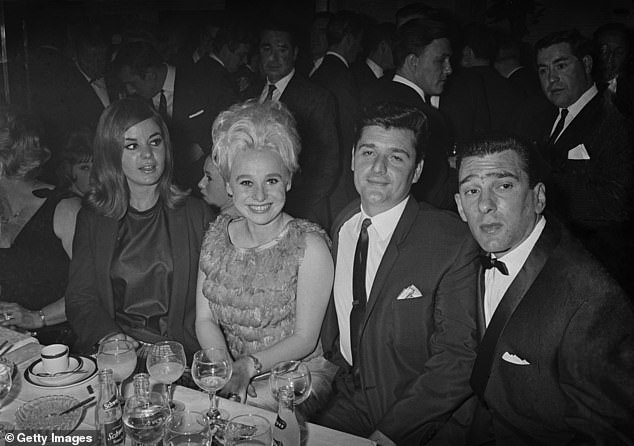

Frances Shea (far left) and Reggie (far left) with Barbara Windsor and her husband Ronnie Knight in Soho in 1965

Maureen Flanagan, a former ‘Page Three Girl’ who was a regular visitor to Vallance Road in the Sixties, remembered the brooding atmosphere. ‘Every time Ronnie wanted his twin and Reg said, “I’m with Frances” that would cause even more rows between the twins,’ she explained. ‘And it was even more obvious how much she disliked Ronnie if he turned up while she was there.

‘Her face told you the story. As soon as he came in the door, she couldn’t wait to get out. She’d pick up her bag and say, “Are we goin’, Reg?”’

As she became increasingly down, Reggie arranged for her to see the same psychiatrist who had prescribed antidepressants for Ronnie. After a week in a private hospital, she moved in with her parents who forbade Reggie from even entering their house.

Once safely back with her family, Frances recounted some of what had been going on. Her husband, she told her mother, was perverted and didn’t make love to her at all.

On one occasion he’d attempted to take her from behind, as if she were a boy. She felt ashamed, soiled, degraded. She said she didn’t believe any other man would want her now. Reggie had no intention of staying away and letting her get better. Instead, he stood outside the house in the early evenings and talked to her as she stood at her open bedroom window.

It would have been romantic if he had not then got back into his car to be driven back to his smoke-filled clubs, his twin, the hostesses, the minders – the life he couldn’t relinquish for the love of Frances. Rather than searching inside himself to understand why his wife, so fragile emotionally, had been driven to breaking point following her exposure to his crazy and scary world, he blamed her family for the breakdown of the marriage. They’d interfered, he’d thunder to himself in his brooding drunken rages. He’d show that old cow Elsie, Frances’s mum, what Reggie Kray did to people like her.

He sent anonymous letters to Frank Senior, Frances’s dad, saying his wife was sleeping with other men. He wrote to the men Elsie worked with, claiming she was anyone’s for the asking. He even got someone to go round to the Shea house in the dead of night and damage the family’s Mini.

Things only got worse as Ronnie’s illness created the terrible unpredictability that culminated in the shooting dead of rival gangster George Cornwell in the Blind Beggar Pub in Whitechapel in March 1966.

A pointless murder carried out by a homicidal schizophrenic, and played out in full view of the pub’s staff and customers, it confirmed to the Shea family what they were dealing with – something way beyond anyone’s control, including the law.

Two weeks after the Cornell killing, with Ronnie in hiding and Reggie making sure that witnesses knew exactly what would happen to them if they didn’t keep their mouths shut, Frances visited a firm of solicitors and changed her surname back to Shea by deed poll. She then told Reggie that she wanted the marriage annulled because it had not been consummated. He said he would handle the petition through his solicitors but in reality he did nothing.

Frances was now more or less dependent on her medication. The smallest thing could have her reaching for her packet of pills, legally prescribed by the doctors and now a consistent feature in her life. She was in a bad way and spent several months in a psychiatric ward at the local hospital where she was given ECT (electro-convulsive therapy) as well as drugs four times a day.

The young woman who finally left the hospital in the autumn of 1966, just before her 23rd birthday, was nothing like the beautiful bride in their wedding photos, taken by David Bailey.

‘She looked drawn, like someone who had just given up,’ remembered her friend Maureen Flanagan. ‘It was all too much for her. She could never be scruffy or untidy, but she had no make-up on, was pale, white as a ghost, like a little will-o’-the-wisp: not really there.’

That October, she was readmitted to hospital after taking an overdose of barbiturates.

Another suicide attempt in January 1967 saw Frances barricading herself into the front room of her parents’ house, and turning on the gas fire without lighting it. Her father found her in the nick of time. But that June, by which time she was staying with her brother Frankie, he took his sister a cup of tea in bed one afternoon and found her dead.

She’d taken a huge number of sleeping pills and there was a strange half-smile on her face that was to haunt him down the years. To Frankie, it was as if she was saying: ‘I’m happy now.’ His beautiful sister had found her way out.

Reggie, upon seeing Frances lying there, lifeless, lost to him for good, was overwhelmed with grief. He drank himself into oblivion that afternoon and spent the night on the floor beside her body, weeping and wallowing in his hatred for the Sheas. He believed them responsible for this terrible thing. He wanted to kill them.

What happened next was a measure of his dogged determination to possess Frances Shea to the grave and beyond. After she had been taken to the mortuary, he didn’t waste a minute, driving around to her parents’ house and then her brother’s flat, and demanding every single item belonging to Frances. Her engagement ring. All her jewellery. All the letters between them. Even her make-up.

There was no pity or concern for the family of the girl he claimed to love, just a savage ransacking of Elsie and Frank Shea’s daughter’s life, both to terrorise them and lest anything in her belongings might betray his image and incriminate Reggie as the monster controller he was.

Ignoring the family’s wishes, he insisted she would have a send-off befitting her celebrity status. ‘I’d given her the East End’s wedding of the year,’ he told John Pearson, author of a history of the Krays. ‘Now I was giving her the East End’s funeral of the year.’

Costing today’s equivalent of around £30,000, it was as ostentatious as Reggie wished and the more modest wreaths from Frances’s family were dwarfed by enormous floral displays from the Krays’ underworld contacts. They daren’t send anything less, as Reggie’s right-hand man Albert Donoghue recalled. ‘I had to go and check all the bouquets, see who had sent flowers and then tell Reggie who’d been missing,’ he said. ‘He’d remember that. It was sick.’

After the service, the mourners were transported in ten huge black limousines to Chingford Mount Cemetery, where Reg had purchased a large burial plot, his intention to be buried there with Frances, along with all the other members of the Kray family.

At the grave, as his wife’s coffin was lowered into the earth, Reggie wept as everyone watched in silence. It was a classic Hollywood performance, a ritual demonstrated to show the world how Reggie Kray had loved and lost his wife.

As Reggie’s right-hand man, Albert Donoghue said: ‘He was a good actor. If Frances was mentioned afterwards, he’d start to cry. It was either remorse or acting.’

Within a few months, the grief-stricken husband would be finding comfort in the arms of a 23-year-old woman but he looked haggard and drawn. Tormented, drunk nearly all the time, and more under the influence of his twin than at any time before, Reggie now started to take out his rage on virtually any random target, egged on by Ronnie.

Helpful as ever, Ron told him about a small-time criminal, who had been rude about Frances and Reggie went round to the man’s house and shot him in the leg. Another man was knifed for some half-imagined slight.

Both victims survived so this wasn’t enough for his twin who kept reminding him that he hadn’t yet done what he, Ronnie, had done that night in the Blind Beggar pub. Only murder by Reggie’s hand, he insisted, would seal their bond, reinforce their legend as killer twins.

By now, Reggie was teetering on the edge of a breakdown and the increasing amounts of drink and drugs he was taking as a result of Frances’s death may well explain why just four months later he so brutally stabbed to death Jack ‘The Hat’ McVitie, a fellow gangster who had bottled out of killing someone but kept the fee the twins had paid him.

Since this and the murder of George Cornwell were the crimes which finally led to the twins being sentenced to life in jail at the Old Bailey in March 1969, it might be argued that Frances had played an indirect role in bringing about their downfall from beyond the grave.

Yet, as ever, it was Reggie who sought the upper hand and he got his revenge on her and her family with the extravagant Italian marble headstone he had engraved for her.

In one of her suicide notes, Frances referred to having changed her name back to Shea and expressed relief that this would be the name on her headstone. But instead it read ‘in loving memory of my darling wife Frances Elsie Kray’.

All attempts by her family to have the headstone replaced with one bearing Frances’s maiden name were blocked by Reggie.

There it remains to this day. And even close to half a century on from her suicide at the age of 23, total strangers visit her final resting place, place flowers on her grave and ponder the short existence of a young woman who remains permanently linked to the evil Kray twins.

© Jacky Hyams. Adapted from Frances Kray – The Tragic Bride by Jacky Hyams (John Blake, £9.99). To order a copy for £8.99 (offer valid to 26/04/25; UK p&p free on orders over £25) go to mailshop.co.uk/books or call 020 3176 2937.