This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

British liberalism has become the nation’s religion. It establishes the parameters for what may legitimately be said, and done, in public — and, increasingly, in private too. This is as true for the Conservative Party as it is for Labour, the civil service, the media class, the intelligentsia, the academy (which is not the same as the intelligentsia), the courts, the police, the trade unions, the Church of England (and Church of Scotland), the monarchy, the Liberal Democrats, the Greens, the Scottish National Party, the quango complex, the charities, the museums and others besides.

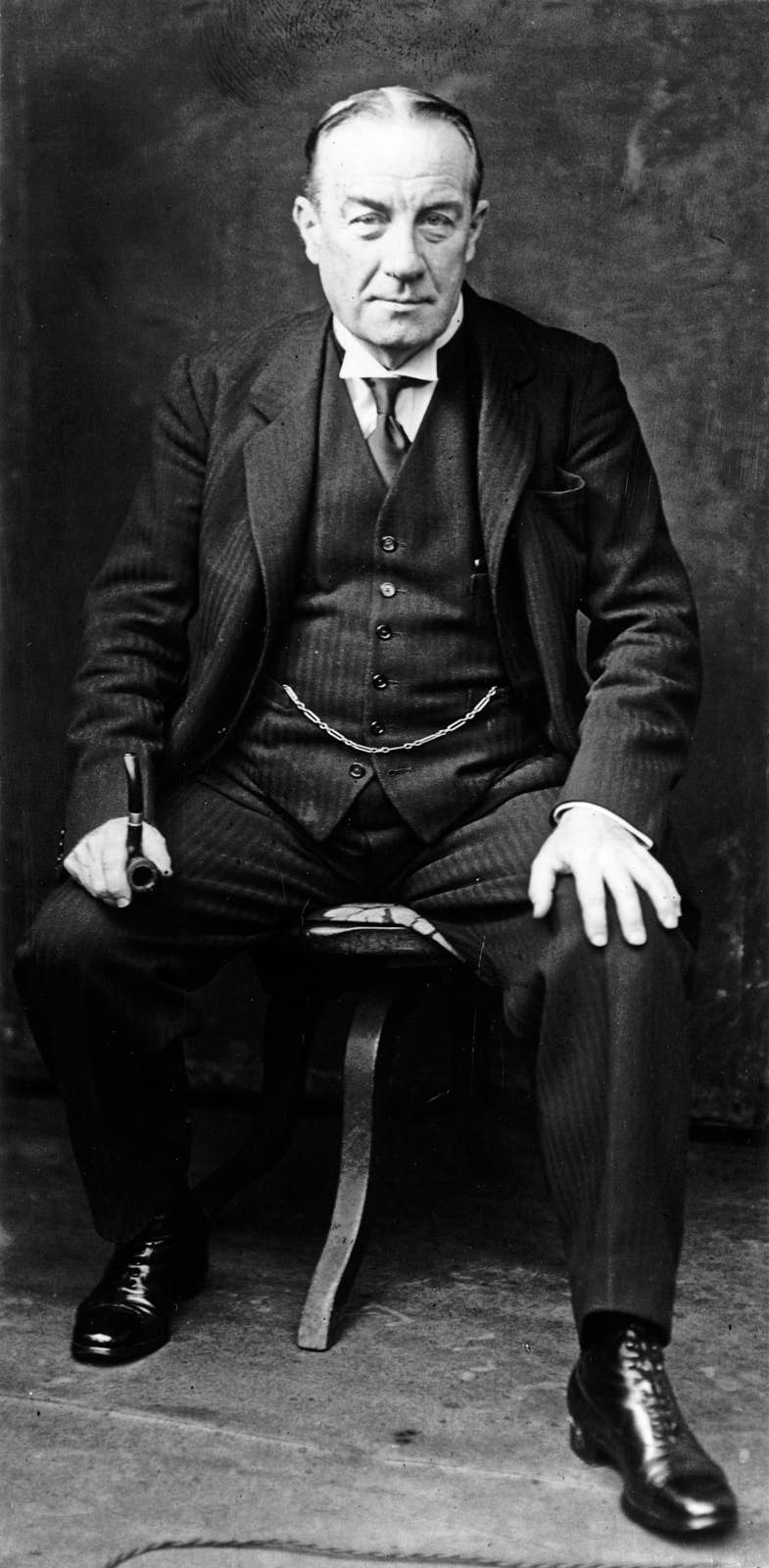

Liberalism of this sort is not merely a political language, but a state of mind with strong totalising tendencies. It resembles what the reactionary Cambridge historian Maurice Cowling called a “public doctrine” — and an extraordinarily potent and effective one, at that. It exerts a powerful hold over the mind of the governing class. Opponents have been driven to the margins and denied significant parliamentary representation, despite their popularity. They have even been criminalised.

For Cowling, a public doctrine was a framework of rhetoric and values that may be worked up by politicians, journalists, intellectuals and others. It is a series of assumptions and maxims, a worldview, and a message. In the hands of ambitious politicians capable of packaging and selling it, it not merely channels, but actively shapes, the political agenda; appeals to emotions and prejudices; identifies enemies; and suggests directions of policy. It situates action within a set of linguistic coordinates.

In this, public doctrine is far from an innocent business. Politicians use language for effect. There is always a correlation between the doctrine being sold and the interests of the individuals, parties and institutions that stand to benefit from it. Public doctrines are intended to secure and retain authority, as well as to deny it to others.

To this end, it is not, simplistically, the case that doctrine prescribes activity; rather, action often comes first, with practical political activity then generating what Cowling’s student Michael Bentley termed “doctrines of explanation and benediction”. Humans have a tendency to formulate doctrine in order to varnish their behaviour. Public doctrine is as much a consequence of activity — a rationalisation, a justification — as its origin point.

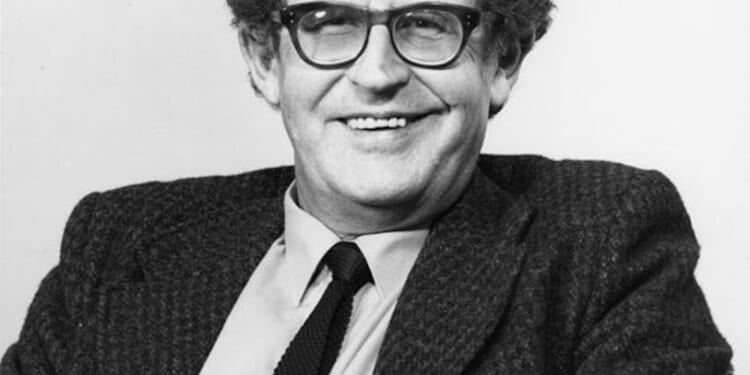

Some individual leaders have been successful in framing public doctrines that structured political life for a prolonged period. Think of the dominant figure of interwar British politics at the birth of mass democracy, Stanley Baldwin. He was a prolific public speaker, constantly stressing themes of patriotism, moderation and constitutionalism that resonated with electors.

At other times, outstanding individuals have perhaps been less significant, with public doctrines the fruit of a larger, broader alignment between the governing class and the clerisy. Think of the post-war consensus on economic and social policy between the 1940s and the 1970s. It was hegemonic in the parties, Whitehall, the media, the unions and the universities — and remained so despite the economic tumult it provoked.

The determination of Thatcher to overturn it and offer a new public doctrine triggered an extraordinarily rancorous struggle. Emotionally speaking, the adherents of the “consensus” never recovered and spent the rest of their careers — indeed, their lives — lamenting better days. Public doctrines sometimes die hard.

The doctrine that dominates modern Britain is, similarly, the work of many. And this makes it robust. This contemporary liberal order has been highly effective in acquiring and retaining power. It has proven, in the words of the philosopher Ken Minogue, “marvellously fertile” in inventing justifications for doing so.

If liberal public doctrine has one central source of authority, it is the dogma of multiculturalism. To prefer the way of life inherited from ancestors, to favour existing and proven habits, to imagine that British society may be better than others, and to contend that other cultures could be inferior or incompatible, has become to be seen as a retrograde and morally unacceptable judgement.

Liberal multiculturalism seeks to deter, if not prohibit, this sort of thinking. It does so, rather sneakily, by linking race together with culture. Critiques of the latter (for example, to ponder why lots of Pakistani migrants and their descendants have failed to assimilate) become bound up with the crude nastiness of the former. This is a disreputable trick, but it has proven a consistently effective one.

So, too, the slippery lack of definitional clarity as to what, exactly, racism is. The boundaries of what is called racist are ever-expanding. All cultures are to be treated as equal in value, despite their different standards; to challenge this is to think in “colonial” terms.

As Minogue had it, “The cutting edge of multiculturalism … is to be found in its insistence that the Anglo-Saxons and Celts of Britain must not think their language, religion, laws and customs in any way superior” to those millions who have left other parts of the world — whether Asia, Africa, the Caribbean or Europe — to settle here. (The fact that there is usually little “reverse traffic” to speak of is best not pondered; so too the fact that many of the places from which migrants come are profoundly dysfunctional.)

Multiculturalism is a particularly appealing organising concept because to propound it is to tell the world that one is open-minded; and that is a source of social capital — a means of mutual identification — for liberals. Of course, there are other sacred subjects, as well: further manifestations of identity politics such as “protected characteristics”, the Equality Act, Net Zero, the European Union, “the rules-based international order” and, inevitably, “our NHS”.

The linguistic borders of liberal doctrine are heavily fortified with moral artillery: words such as racism, sexism, Islamophobia, homophobia, bigotry, prejudice and discrimination provide a means of writing, speaking and acting. This is a public doctrine about purity of the heart. Liberal dogmas seek to persuade people to feel certain emotions rather than others. To dissent is to be unworthy.

Liberal statecraft, in contrast, boasts glaringly few discernible policy ambitions. Perhaps the only one of note over the past decade has been provided by Theresa May and Ed Miliband with their economically radical Net Zero. But its sentiments are utterly dominant in the civil service. As the Cabinet Secretary Gus O’Donnell perceived his duty, “I think it’s my job to maximise global welfare not national welfare.”

Liberal hegemony is highly visible in the law (when I recently rang the police to report a crime, I had to sit through a lengthy automated message first about what to do if I had been a victim of “hate”). It structures media coverage of national and world affairs, particularly via the broadcasters. There is no escape from it. The academic sector is beyond salvage, as curricula are rewritten to promote doctrinal ends. It is hard to find a television drama produced in the past decade that does not beat one over the head with its message.

Liberal public doctrine is also conspicuously authoritarian. Phrases such as “offensive”, “inappropriate”, “hate” and “problematic” are now the standard currency through which public affairs are discussed and critics deflected. Double-standards abound, and are increasingly enshrined in law. Making jokes about foreign culture or to critically discuss religions (other than Christianity or Judaism, of course), is now likely to be a matter for human resources or perhaps the police.

Even using the word “foreign” is not ideal (“international” is preferred). To step out of bounds — in other words, to say something that liberals don’t like — is to risk a great deal. Language about what is to be done is often more important than the substance of what is to be done.

This is a doctrine — as Cowling wrote of John Stuart Mill — of “sneers and smears and pervading certainty”. Dissent is permissible only under narrow, and receding, conditions. Censorship, re-education through training and guilt by association are all part and parcel of contemporary life. There is little faith in democracy, and decision-making has largely been transferred to liberal lawyers and quangos instead.

All of this is in the service of those who benefit from, and wield power through, the liberal system. Carl Schmitt, with his friend-enemy distinction, would be proud. Crucially, it is highly unpopular with the British public. We all know this. Our politics is characterised by rage, alienation and disengagement.

Liberals respond with animus. In 2016, the voters proved unworthy of their ruling class when they voted for Brexit. This has never been forgiven and led to tighter controls in the years afterwards. Liberals remain deathly afraid of the public, and the liberal regime has essentially chosen a dual strategy of cultural and legal antagonism combined with party-political neglect and disdain.

Liberalism has, then, become the de facto state religion of the modern British state. It is a godless religion, yet still one that insists upon submission to its doctrines and the punishment of heresy. It is also a morally shallow religion, with little room for forgiveness and no objective beyond control (“you can’t say that”). But then — as the sociologist Christie Davies pointed out — sources of moral argument have become rare in post-war British life.

There are, occasionally, half-hearted attempts to recategorise liberal public doctrine under the guise of “British values”, but this is empty talk. When probed, “British values” turn out to be merely the generic pieties of Equality Act Britain, combined with waffle about fish and chips and William Shakespeare, before running out of steam after a few sentences.

Those on the political Right often conclude that liberalism is well-meaning but misguided. There is certainly something to that — liberals do often seem staggeringly naive about the human species — but it is insufficient. The reality is more troubling. Liberalism has evolved into a profoundly destabilising force. The dogmas of multiculturalism have wrought social disaster.

Disproportionate levels of criminality, anti-social behaviour and extremism amongst many immigrant demographics — regardless of whether they came legally or illegally, and whether they are themselves migrants or their descendants — pose an acute risk to public safety. Terrorism, gun and knife crime, sectarianism, sexual abuse, drug gangs; Britain has it. In the face of this, it is ordinary Brits who are having to “integrate” and adjust their customs and expectations accordingly.

The refusal of liberal politicians of both major parties to acknowledge public preferences across a whole range of policy areas acts to delegitimise the parliamentary system. It is now well established that the fact that people such as social workers, councillors and police officers were terrified of being labelled “racist” — the worst infraction against the liberal religion — was central to the unwillingness of the authorities to tackle the worst grooming gangs. These crimes are racially and religiously aggravated, have been an alarmingly prevalent practice amongst those of Pakistani heritage and are committed against children.

Yet the liberal conscience must be protected at all costs. And so the sexual abuse was allowed to continue. This is why Minogue judged liberalism “a prolific generator of fanaticisms”. The governing class could not stomach the challenge that these crimes posed for their worldview of multiculturalism, and the patronising fetishisation of “minorities”. Racism is worse than child rape, apparently. Nobody would say that outright, of course, but actions speak louder than words.

There remains a widespread tendency to look the other way or to attack those who dare point out these crimes and cry “bigot”. The electoral risks of discussing it are explosive, not least for a Labour party simultaneously chasing white voters in post-industrial England and Muslims. But Conservative politicians didn’t want to be called “racist” either. This is a doctrine with substantial psychological power. As Anthony Browne argued, the first reaction of many in contemporary society when confronted with public policy problems, “is not to try and divine the right answer but the politically-correct one”.

That amounts to reprogramming at civilisational scale. So in Rotherham and other places, victims were blamed for being abused. Liberal politicians would often descend into violent hysteria when confronted with the subject. Damningly, they continue to do so.

The challenge for the right is to devise a doctrine capable of upending its liberal counterpart

If liberalism has a tendency to develop salvationist projects, what kind of earthly salvation is on offer here? As Minogue witheringly concluded, liberalism constitutes “a very odd form of morality indeed”. Such is the ascendant, hegemonic public doctrine of our time.

Considering the long success that liberals have had in setting the tone of public life in Britain, it would be foolish to bet against their continued rule. At the same time, a public doctrine that has few ambitions for rescuing the country from its decline, and which has little to offer beyond surveillance of what people say, is plainly not much use to us.

The challenge for the political right is to devise a public doctrine capable of upending its liberal counterpart. Perhaps the most important dilemma facing the right is whether to agree with liberals that political action and allegiance ought to be a matter of “identity” and hinge upon a rejection of compromise and the identification of enemies. A great deal depends on the response to this. As Betrand de Jouvenel observed, the essence of prudent statecraft is to come up with a correct answer at the appropriate moment.

Given the fatal split of the British right into three camps (Conservatives, Reform, Cheesed Off), there is much work to be done. Whether its current political leaders possess the capability is, I am afraid to say, a question of existential intensity. The stakes could scarcely be higher.