This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

One function of words imported from other languages is to remind you to enjoy simple pleasures that other cultures care about enough to name. Flâner is an invitation to stroll like a Parisian; craic to laugh with friends like a Dubliner; hygge to cosy up in winter like a Dane.

More useful, however, is a borrowing that describes a problem in your own culture that, for lack of a name, is misunderstood. Which brings us to voluntarismo, a word used in political commentary across Spanish- and Portuguese-speaking South America.

Dictionaries offer two translations. One is the belief that voluntary associations are the best way to provide social welfare. The other, closer to the mark, refers to a strand of German philosophy that regards the will as more important than the intellect. But political voluntarismo is narrower than this: it’s the belief that policies can succeed by sheer determination.

The slogans of the voluntarista resemble “performative utterances”, a term coined by philosopher J.L. Austin for statements that don’t just name something but change something, for example “with this ring I thee wed”. Said at the right time, these words don’t just express an intention to marry, they make the marriage happen.

Consider the slogans “Make America great again” and “take back control”. Their point isn’t merely to express wishes but to make them come true. Wearing a MAGA hat is like clapping at a performance of Peter Pan, except that what’s revived isn’t a dying Tinkerbell but a dying nation.

English offers no more specific word for this than populism, a style of politics that pits a virtuous people against a hated elite. Since 2015, when David Cameron promised a referendum on EU membership and Donald Trump said he would seek the Republican presidential nomination, use of the words “populist” and “populism” roughly doubled, according to Ngram Viewer. In 2017 the Cambridge dictionary declared “populism” its word of the year.

◉ ◉ ◉

The two types of politics do share features, in particular, a hatred of experts. For the populist, experts are part of the elite. For the voluntarista, their obsession with costs and evidence is talking the country down. If belief makes good things happen, then scepticism is treachery.

But not all voluntarismo is populist. Trans ideology, the belief that a person’s sex is whatever they say it is, is quintessential voluntarismo. It is also an elite project, unpopular with almost everyone except academics, young graduates and the chattering classes.

Conversely, not all populism is voluntarista. It encompasses politicians as varied as Argentina’s Carlos Menem, Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro and Venezuela’s Hugo Chávez. Menemism combined personality cult and neoliberal economics. Bolsonaro, a former army officer, emerged from the congressional bloc known as bíblia, boi e bala (bible, beef and bullet). Of the three, only Chávez was a voluntarista, promising to resolve hyperinflation by fiat.

Hyperinflation, South America’s besetting sin, is generally a sign that a voluntarista has been at work. It starts with wages or benefits, usually both, rising faster than productivity. That fuels demand, and prices rise in response.

In a mature economy, the central bank raises interest rates to repress demand — taking away the punch bowl as the party is getting started, as a famous saying has it. But in countries where institutions are weak, a voluntarista can gain power by promising that the party need never end.

That means exhorting retailers not to raise prices, and when this fails, bullying them. Next come price caps. Producers leave the market, shops sell out and the economy falls into chaos. Under Chávez’s protégé and successor, Nicolás Maduro, annual inflation peaked in 2018 at 80,000 per cent.

◉ ◉ ◉

Sometimes, voluntarismo becomes fossilised. Brazil’s constitution, written after the end of military dictatorship, prescribes a workers’ paradise in detail. It is a monument to hyper-indexation, guaranteeing public sector pay, benefits and pensions will keep pace with or outstrip inflation.

Rather than creating the full employment, rising wages, excellent education and universal healthcare it promised, it bequeathed ever-rising public spending, stubborn inflation and low growth.

Seemingly paradoxically, given that voluntarismo depends on willingness to suspend disbelief, it flourishes in times of cynicism about politics.

To get a feel for the depth of that cynicism in South America, consider a couple of successful electoral slogans. One was coined in the mid-20th century by critics of a corrupt but not entirely incompetent governor of Brazil’s richest state, São Paulo. His supporters liked it so much they adopted it, and it’s been used ever since as both criticism and endorsement of any similar politician: rouba, mas faz — he steals but he gets things done.

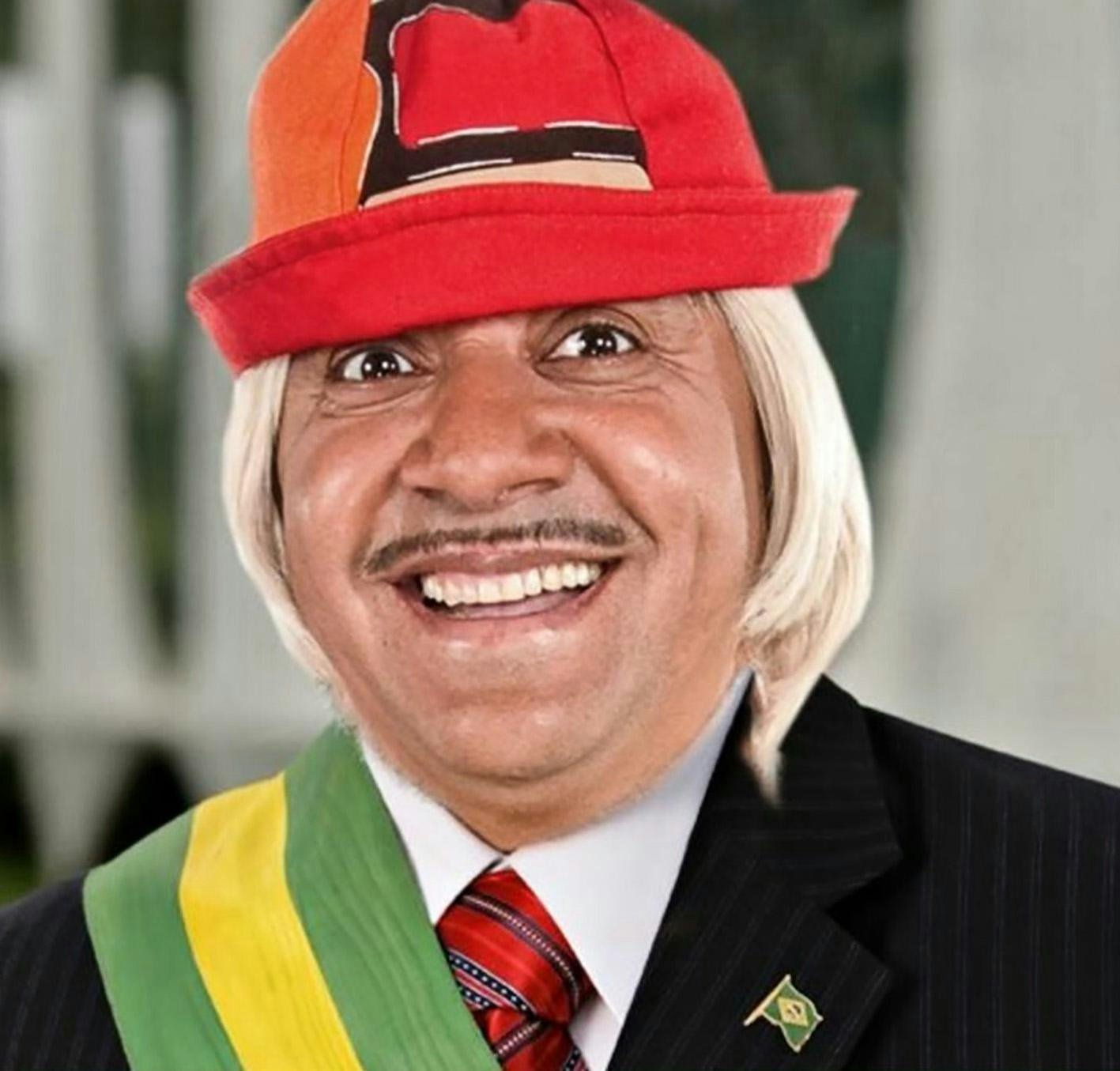

More recently, one of Brazil’s most successful vote-winners has been Tiririca (roughly translated, Grumpy), a clown who had a TV show before standing for Congress in 2010. He gained the highest vote share nationally with slogans such as “What does a federal deputy do? Honestly, I don’t know, but vote for me and I’ll tell you” and “Vote for Tiririca! Things can’t get worse”.

But cynicism is unsatisfying. The politician who steals doesn’t get enough done, and things can always get worse. So those who vote for thieves and clowns are surprisingly easy to seduce with implausible promises of national renewal.

◉ ◉ ◉

The appeal is heightened when the economy is stagnating. Voluntarismo doesn’t just promise that good outcomes are possible without effort or sacrifice but that mutually incompatible outcomes can be achieved simultaneously.

And voters’ demands are always incompatible. Each interest group — workers, pensioners, the unemployed and so on — naturally rates its own claims highest. What helps reconcile their demands is economic growth, which allows a government to serve each group a larger-than-fair slice of the pie in the confident expectation that the pie will soon be larger.

None of which bodes well for the UK, where political cynicism is rising and economic growth is a distant memory. A record share of 45 per cent of voters now say they almost never trust governments of any party to put the nation’s needs above party interests and a record 58 per cent that they almost never trust politicians to tell the truth when they are in a tight corner.

Since the financial crisis of 2008, most rich countries have struggled to revive their economies. But the UK’s growth per person — that is, stripping out the effect of high immigration on the total population — has been the lowest in the G7. Meanwhile the tax burden is at its highest as a share of GDP since just after the Second World War.

So it is hardly surprising that a voluntarista, Nigel Farage, is the bookies’ favourite to become the next prime minister. Reform’s economic pledges are pure voluntarismo: to slash taxes and maintain spending on benefits, in particular the “triple lock” on pensions introduced in 2010 — a hyper-indexation policy that would look perfectly at home in Brazil’s constitution. Apart from cuts to foreign aid, which is a trivial part of total spending, the only nod to making the sums add up is a vague mention of “efficiency savings”.

◉ ◉ ◉

A lot can happen between now and the next election. But once voters become seized by the idea that they can have it all, it is hard for any politician to preach prudence. The Prime Minister has already reversed course on removing winter fuel payments from well-off pensioners and is committed to keeping the triple lock. Kemi Badenoch’s near-silence on economic policy since becoming Tory leader suggests that she is frozen between being dishonest and being unelectable.

Blessed with an independent central bank, the UK will be spared a South American wage-price spiral. But the higher interest rates required to prevent such a catastrophe will harm growth and worsen the rows over scarce resources that made voluntarismo seem so attractive in the first place.

How it all ends depends on whether the country’s economic and political institutions retain enough strength and integrity to prevent a crash — and on whether, if one does come, it is used as an opportunity for necessary reforms. Voters will never blame themselves for falling for voluntarismo. But if things have been bad enough, for long enough, they may regain their taste for truth.