Plain packaging will not stop people from vaping — and it is wrong to demand it

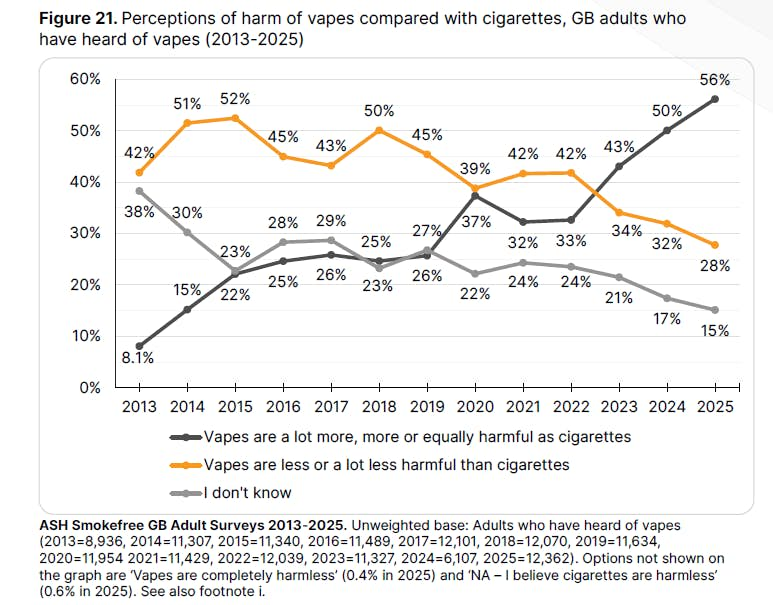

The epidemic of misinformation about the risks of vaping is one of the great public health disasters of the century and is all the more shameful for having been driven by people who have words “public health” in their job titles. The “popcorn lung” myth, the EVALI hoax and an endless series of tabloid scare stories — combined with the enduring misconception that nicotine causes cancer — have turned public understanding on its head. As the graph below shows, twice as many Britons think that vaping is as dangerous as smoking, if not worse, than correctly believe that it is far less harmful.

If vaccines or paracetamol were subjected to the same level of misinformation, public health professionals would be working frantically to move the public’s perceptions towards reality. Insanely, they are doing the opposite. The government’s Tobacco and Vapes Bill will give the health secretary Henry VIII powers to regulate vapes like cigarettes, thereby cementing the notion in the public’s mind that the health risks are comparable. The government is being cheered on by a motley assortment of fork-tongued “public health” academics and activists who pay lip service to the benefits of e-cigarettes while doing everything they can to suppress demand for them.

A particularly egregious example of this was reported by the Independent this week. Members of the tiny, state-funded, prohibitionist pressure group Action on Smoking and Health have teamed up with researchers from King’s College to demand plain packaging for e-cigarettes. There is, of course, only one other product that comes in plain packaging: combustible tobacco.

Their study, published in Lancet Regional Health, uses the same shoddy methodology as the dozens of studies that were conducted a decade ago to push for plain packaging of tobacco. The researchers showed people e-cigarettes in normal packaging and then showed them a mock-up of what plain packaged e-cigarettes would look like and asked them which one seems more appealing. Obviously, most people say that the branded packaging looks better than the packaging that has deliberately been made boring and this is interpreted by the authors to mean that fewer people would buy the product if the branding were removed.

We know from our experience with plain cigarette packaging that this is not how it works. The anticipated drop in cigarette sales after plain packs hit the shelves in 2017 never materialised. But “public health” academics cannot afford to be dispirited by dismal failure, so they are trying again.

There is, however, a complication. The authors concede that “vape packaging regulations need to strike a delicate balance between not dissuading people who smoke from using the products to quit smoking, whilst also dissuading youth and people who have never smoked from trying them”. This is awkward because all the junk science which suggested that plain packaging for tobacco would work also suggested that it would deter adults and adolescents in equal measure. In the new study, the authors get around this by asking adults and minors different questions. While the adults were asked “Which of the following products would you be most interested in trying?”, the adolescents were asked “Which of the following products would people your age be most interested in trying?” The authors claim that it would have been unethical to ask a minor if they want to buy an e-cigarette, but it makes an important difference because people tend to believe that other people are more susceptible to marketing than they are themselves.

Sure enough, the youth said that their peers would be likely to buy a vape in plain packaging. Non-smoking adults also said that they would be less likely to buy a vape in plain packaging. Alas, adults who smoked felt the same way. So did adults who vaped. Deterring smokers from taking up vaping is the one thing we are trying to avoid. We also don’t want to see vapers going back to smoking. This study suggests that plain packaging for vapes could do both.

Burying the lede, the authors focus on a peculiar finding in the study which suggests that if you put a vape in plain packaging and change the name of the product (so that Blue Razz Lemonade becomes FR17, for example), it deters non-smokers but doesn’t deter smokers. This seems surprising, to say the least, and the evidence for it is not terribly strong, but perhaps it doesn’t matter because we know that what people say in these surveys doesn’t translate into behavioural change.

Even if it did, so what? In this study, putting a vape in plain packaging and changing its name increased the number of non-smoking youngsters who reckoned that their mates would not be interested in buying the product from 26.2 per cent to 29.5 per cent. This is utterly trivial. What matters is that 56 per cent of the general public are so ignorant that they think vaping is as bad for their health as smoking — or worse — and the figure for smokers is only a fraction lower (53 per cent). Applying regulation that is uniquely associated with smoking to e-cigarettes is bound to send a message to the public that the relative risks are indeed commensurate. Health warnings, advertising bans and plain packaging were all applied to cigarettes because, so we were told, the risks of smoking are off the scale compared to the risks of other consumer products. Cigarettes are, we are told, a “unique product” that demands unique regulation. Dusting down the anti-tobacco playbook and rolling out the same old policies for a product that is not only vastly safer than cigarettes but is a direct substitute for cigarettes is not just tedious and predictable. It is dangerous.