This article is taken from the July 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

“A spectacle” might be the best collective noun for architects en masse but strictly for the eyewear. The Venice Architecture Biennale is more restrained than its brash, arty big sister; too cerebral for the gaudy migrants of the kunstcaravan circuit. Both events trumpet their commitment to revolutionary perspectives, but, whilst the parties and the clothes may be less extravagantly absurd, Architecture Biennale has the stronger claim to actual solutions (plus more participants who can actually draw).

This year’s curator, Carlo Ratti, has taken the radical step of suggesting that intelligence might be the key not just to improving the future of humanity but ensuring it has one, hence 2025’s theme, Intelligens, asks how clever people can re-prepare the planet for survival. Ratti identifies architecture as a key discipline in negotiating climate change between two possibilities which will require completely different buildings and infrastructures: one in which the world has respected the Paris accords and one in which it has not.

If only the USA had heard about the clever bit earlier. Porch: An Architecture of Serenity at Giardini was doubtless a charming idea when it was conceived; now it is a grim satire. Incorporating a hefty wooden stoop in front of the pavilion’s classical façade, it aimed to replicate the porch as a site of connection and communication between generations of rural and urban communities: “Here on the Porch, we’ll sing, dance, laugh, learn, play and remember together!” On press day, a sweet folk duo were encouraging the jaded journos to sing along to “If I Were A Mountain”. Perhaps it’s kindest to consider Porch as an elegy.

Over at Arsenale, the curatorial exhibit investigates natural, collective and artificial intelligence over 300 projects. It’s cramped and rather chaotic but absolutely worth a visit for the range of imagination and ingenuity on display. Of the national pavilions, Mexico’s Chinampa Veneta is a joyful immersion in an amphitheatre of discrete floating ecosystems, practical (as a solution for enhanced crop yields) and delightfully playful — the slide show of chinampas gaily invading classic Venetian paintings is buoyant in every sense.

Uzbekistan’s A Matter of Radiance is an impressively polished exploration of the history and potential of the vast Soviet-era Sun Institute outside Tashkent, incorporating a monumental work in glass, Irene Lipene’s Parade of Planets chandelier and a jaunty solar kettle, within a thoughtful examination of the changing perceptions of “ideological” architecture.

Dakh: Vernacular Hardcore at Ukraine would deserve a mention for simply being in Venice at all, but it’s a genuinely strong, as well as inevitably poignant, show, building on the idea of the roof as the ultimate expression of the strength of a building’s foundation. Smell is employed intriguingly at Kosovo’s Emerging Assemblages, where a stark glass mobile emits scents based on farmers’ descriptions, reacting as the viewer moves through the structure.

The winner of this year’s Golden Lion award, Bahrain’s Heatwave, allows visitors to experience an alternative air conditioning system based on traditional Bahraini technology, in which air cooled underground reduces extreme heat in public spaces. It’s not the most visually thrilling pavilion, but its functionality is excitement enough.

Overall, Arsenale’s admittingly overwhelming range of exhibits feels generous, accessible and cautiously encouraging, offering genuine solutions over vacuous provocations. There’s a lot of fun to be had, from trying a ride on a water bicycle to interacting with the solemn man advertising for a wife at the entrance (performance art — hopefully).

Ratti has been criticised for a lack of strict directorial vision and for including too many participants, but both objections seem strengths rather than weaknesses. Amidst the katzenjammer are many fascinating, hopeful and plausible offerings. Yes, there’s a lot to absorb but so much to learn, and a superabundance of clever people doesn’t feel a serious problem.

Back at Giardini, the offerings are more uneven. The central pavilion is closed (hence the squeeze at Arsenale), Russia and Israel are empty and France has opted for a pointless labyrinth of wire trays. Japan offers an AI conversation between visitors and elements of the pavilion itself, in which characters such as “Hole” and “Yew Tree” interact with human discussions. The results are as unilluminating as the technology is sophisticated, which might sum up many of the weaker national offerings.

Poland does better with Lares and Penares, a series of quirky, arresting installations which interpose the needs of conventional architecture with psychological notions of safety. Generally, the mood is more subdued, but there are far fewer wasted opportunities than previous years and nearly all the exhibits merit a visit.

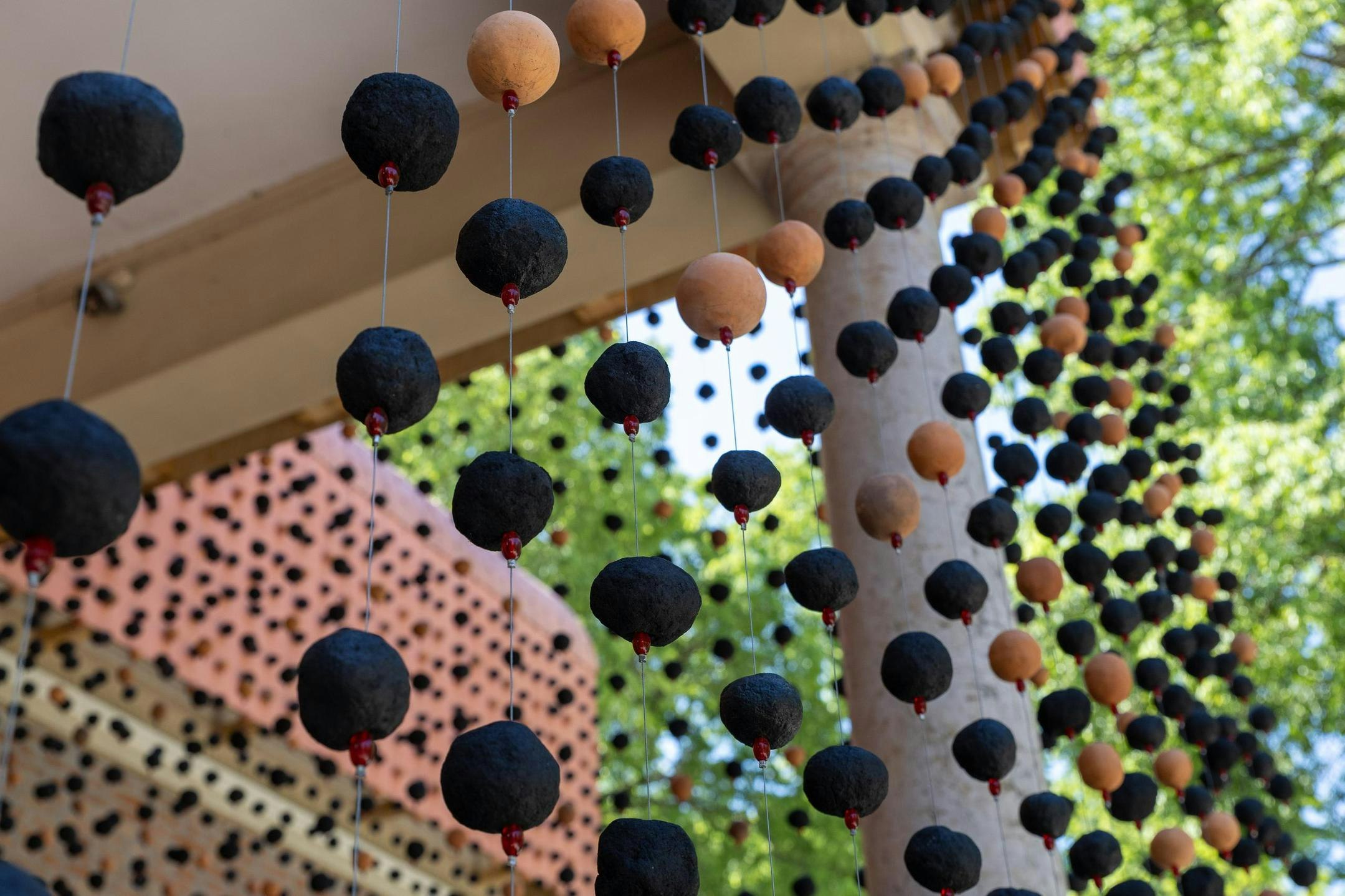

This season’s standout horror is Geology of Britannic Repair at the British Council-sponsored GB Pavilion. The show received a Special Mention from the jury, but I suspect they might have been using “special” in that way we’re not supposed to. A veil of blobs made from clay from India and Kenya shrouds the building, setting the scene for yet another visual comment on colonialism, which lately is beginning to feel like a pretty ragged drum to bang.

The blobs claim to recall Venetian Murano glass beads, fiore, which were used as a “crude imperial currency for the exchange of metals, minerals … and enslaved people”, except that they weren’t, which the curators would know if they had bothered with research instead of idle historical prejudice.

“Slave beads” were so named for the women who made them in Castello, not far from Giardini, and, whilst they were included in the barter packages offered by Atlantic slavers, gunpowder, not glass, was the primary medium of exchange. And the blobs are the best part, so I recommend a brisk about-turn to Austria, which ought to be a compulsory junket for British politicians.

Agency for Better Living is a polemic in favour of the right to affordable housing and the inadequacy of the private sector to deliver it. It celebrates Vienna’s hundred-year legacy of public housing and its continued success in a city where the majority still rent their homes and social provision is seen as the first, rather than the last, option. The show suggests that affordability should not come at the cost of living “gracefully” and demonstrates the advantages, realisable and replicable, of privileging both equally.

The thrill of shucking off prescribed thinking is also in evidence at the Nordic Pavilion, which at first glance looks as though it’s been swapped with the USA. Graffitied muscle cars and a Donald Judd-esque raw concrete garage might look as though the Scandis have simply grown tired of restrained good taste, but close up this is an erudite embodiment of impoverished, unquestioning contemporary consumerism and the pressures imposed by the straitened normalcy of many urban environments.

The two pavilions share a complementary subversiveness which taps brilliantly into Ratti’s vision for this Biennale: that when it comes to what we think about the things we need to own it’s our brains which are in need of fracking.