‘You have breast cancer.’

There are few phrases more frightening for a woman to hear from her doctor, even though the disease has become alarmingly common with one in eight diagnosed at some point in their lifetime.

For many, the most frequent question in return is ‘why me?’

While the diagnosis may seem unfathomably random to those who have always steered clear of the lifestyle factors known to contribute to the growth of breast cancer, those who have been less cautious can be left agonising over the question of whether, somehow, they did this to themselves.

There are few phrases more frightening for a woman to hear from her doctor than ‘you have breast cancer’. (Stock image of a breast screening posed by a model)

One of those women is Corrine Barraclough, a globetrotting former magazine editor who now works in rehabilitation.

While she was a drinker, alcohol nearly ended her life a number of times.

There were multiple occasions she woke up after blacking out, unsure of how she had got home, or what had happened in the intervening hours on her night out.

There was also the time she fell down a flight of stairs, knocking her front teeth out.

And then, in the grips of alcohol-fuelled depression, she once drank bleach.

But, as she bravely wrote in a recent column for DailyMail+, it would be seven years after she got sober that alcohol made its most determined attempt on her life.

‘I felt a hard, pea-sized lump in my right breast,’ she writes.

‘I went for a mammogram, was whisked for biopsies and saw a string of specialists. I was diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer at the age of 48.’

Corrine believes the cancer was caused by her drinking, and points to an overwhelming amount of evidence not just linking booze and breast cancer, but proving it is a leading cause of the disease.

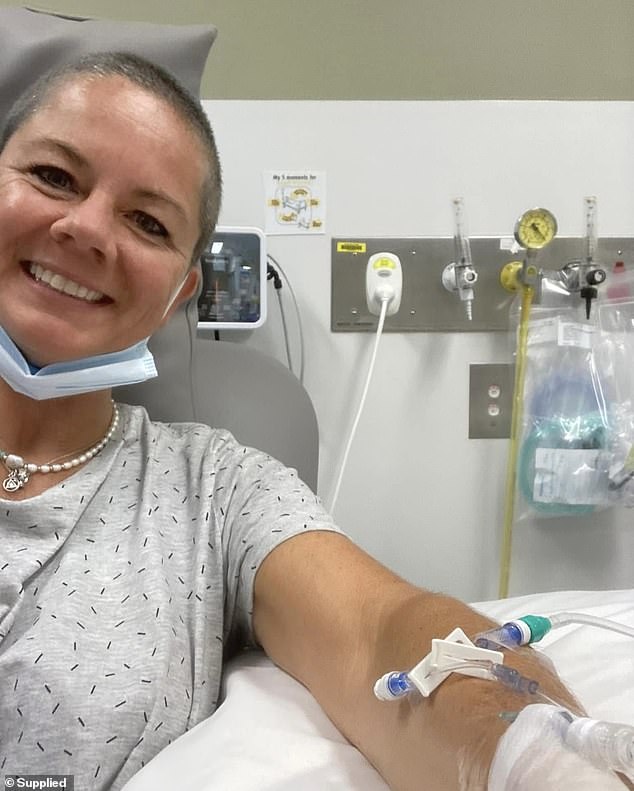

Corrine Barraclough was a daily drinker for decades before finally getting sober in her 40s

Seven years after her last drink, the former magazine editor found a pea-sized lump in her breast and was diagnosed with breast cancer

Alcohol is the leading modifiable cause of breast cancer in premenopausal women

In 2019, researchers from the University of New South Wales found that over 10,000 cases of breast cancer in the next decade would be attributable to regular alcohol consumption.

The large collaborative study led by UNSW’s Centre for Big Data Research in Health was published in the International Journal of Cancer. It pooled six Australian cohort studies including more than 200,000 women and evaluated what proportion of premenopausal and postmenopausal breast cancers could be prevented by modifying current behaviours.

‘I’m still angry about how normalised drinking is in our society,’ Corrine said (stock image posed by models)

Associate Professor Maarit Laaksonen, now at the University of Sydney, was one of the authors of the study, and says it was the first to evaluate the connection between alcohol and breast cancer using the most up-to-date information on how prevalent the risk factors (e.g. alcohol consumption) currently are, as well as to evaluate breast cancer separately in premenopausal women and postmenopausal women (‘as they are essentially considered two different types of cancers these days’).

‘Alcohol has been shown to cause breast cancer both in premenopausal and postmenopausal women,’ Laaksonen tells Daily Mail Australia.

‘Our study showed alcohol consumption to be the leading modifiable cause of breast cancer in premenopausal women in Australia, and the second leading modifiable cause of breast cancer in postmenopausal women after being overweight and obesity.’

Laaksonen explains that if Australian women did not drink alcohol, it would likely have the single biggest impact in reducing breast cancer cases in premenopausal women.

‘Twelve-point-six per cent of cases could potentially be reduced [in premenopausal women] and a significant impact in postmenopausal women too, with 6.6 per cent of cases potentially being reduced,’ she says.

And here’s where the research is particularly concerning: women don’t even have to consume a significant amount of alcohol for their breast cancer risk to increase.

‘No safe level of alcohol consumption’

‘With respect to most cancers, the increase in cancer risk in relation to alcohol consumption is often seen among people who consume two or more standard alcoholic drinks per day,’ explains Laaksonen.

‘Breast cancer, however, is unique in that it has been shown there is no safe level of alcohol consumption when it comes to breast cancer because any level of consumption increases your risk of breast cancer significantly.

‘This is also what we saw in our study, especially in relation to breast cancer in premenopausal women. Hence, when it comes to breast cancer, the safest recommendation would be to not consume alcohol at all.’

But what about all those studies linking a glass of red wine per day to greater health than people who don’t drink at all?

‘It is true that there have been many studies showing what seem to be beneficial results of small amounts (i.e. “a glass of wine a day”) of alcohol consumption especially in relation to cardiovascular diseases,’ explains Laaksonen.

‘Beneficial here refers to those people consuming small amounts of alcohol having apparently lower risk than those not consuming at all alcohol.

‘However, there is one major methodological issue that many studies have not been able to address. Alcohol consumption is typically inquired at the time the study began and the questions about alcohol consumption are about how much that person drinks at that moment.

‘This means that the group of people not drinking any alcohol includes typically lifetime abstainers and those who have drunk alcohol in the past but have quit.’

In other words, the problem with many of these studies (which received an outsized level of publicity and interest from both the alcohol industry and drinkers keen to vindicate their lifestyle choices) is that the ‘non-drinking’ cohort includes people who may have had to stop drinking for health reasons – meaning they had already sustained the damage before becoming teetotallers.

Laaksonen says that in studies that do take this distinction into consideration, it’s the lifetime abstainers who have the lowest risk of death and disease.

‘I think that it is risky to promote health benefits of alcohol consumption, even in small doses,’ she adds, ‘because there are also diseases, such as breast cancer, where any amount is harmful and the safest option would be not to drink.’

Laaksonen believes that alcohol should come with warning labels in the same way smoking does, adding, ‘I think that if alcohol was invented today, it would not be legal.’

‘Big Alcohol’ has a lot to answer for

Corrine, who after six months of treatment and a double mastectomy has now been ‘NED’ (no evidence of disease) since September 2022, believes that quitting drinking when she did ultimately saved her life.

‘I believe that if I had still been drinking, I wouldn’t have been vigilant enough about my health to realise something was wrong until it was too late,’ she says.

‘I was confident in my sobriety before I got sick, but now I am more steadfast than ever. There is nothing like a serious health scare to make you want to take the best possible care of yourself.

‘I’m still angry about how normalised drinking is in our society, though,’ she adds.

‘”Big Alcohol” has a lot to answer for with relentless advertising, much of it targeted at women these days.’

While researchers insist their studies into alcohol and breast cancer are not intended to ‘blame’ women for their disease, they hope the findings empower women to make better-informed decisions about their health and understand there are modifiable lifestyle factors that can reduce their risk.

‘There is no point in me feeling guilty, regretful or angry,’ says Corrine.

‘I have to believe that everything I’ve been through in life can be used to help someone else. That’s what keeps me sober, even just for today.’