Opera seria from the old days can be pretty silly, one way and another, but Handel’s 1737 effort really pushes the envelope with not one but two last-second rescues from fearsome monsters, and a talking volcano — things which prompted his bassoonist Frederick Lampe to whip together a parody, The Dragon of Wantley (in which the Yorkshire-based beast’s Achilles heel is in its arse: it is finally dispatched by the alcoholic hero equipped with a special pair of winklepickers). The Dragon was, incidentally, massively more successful than any Handel opera, racking up seventy performances in its first run. The boss, meanwhile, was working himself to death reviving old pieces for a couple of performances each and churning out three entirely new three-hour pieces in a couple of months, each of which would run for only a handful of nights. In the spring this all caught up with him and he suffered a physical and mental collapse which took him months to recover from.

Giustino is far from rubbish, though it’s not in the same league as the great pieces of 1735, Alcina and Ariodante. But it has a likeable spirit and hero, it’s very positive, with lots of cavorting trumpets and horns, and is basically three hours of harmless fun, charting the rise of the Byzantine emperor Justin I from shepherd to king. Or, well, maybe. It seems to me that Handel pretty much invented the superhero-in-his-dreams format right here (although Joe Hill-Gibbins doesn’t stage it that way). What happens is that the shepherd boy falls asleep and is “summoned” by the goddess Fortune to perform various heroics to save the emperor Anastasio, and his wife Arianna, from the treacherous plots of royal advisor Amanzio — who, among other things, sets a wild bear on Anastasio’s sister and then throws Arianna to a ravening sea monster, both matters dealt with rather summarily by Giustino.

We get all the main bits of this, cut down to two-and-a-bit hours, performed in extrovert fashion by conductor David Bates and his specialist band La Nuova Musica in the basement theatre of Covent Garden. But it’s a Royal Opera show, with their resources, a decent run of performances and a sturdy cast, and part of a commitment to performing plenty of Handel, including marginal stuff like this, in the building. The only previous performance I can recall here is a marvellous and rather sweet student job fifteen years ago by Trinity College of Music in the Old Royal Naval College chapel at Greenwich.

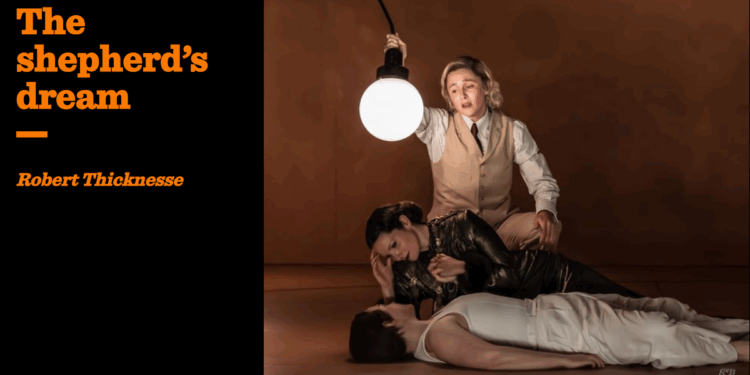

The director here is Joe Hill-Gibbins, an eminent young straight-theatre guy who staged a memorable and original Marriage of Figaro at ENO in 2020. How would he cope with the somewhat specialised demands of this kind of thing, where a four-line aria can go on for ten minutes? He’s a very physical director who likes to work with an empty stage and develop drama and relationships through a build-up of glimpses into the heads of the protagonists, often done through showing us their imaginings (usually based on sexual jealousy, as they visualise their beloveds getting frisky with rivals). That’s a smart way of getting some action going during these long pieces. The downside is that the constant bustle (there’s also a small chorus who do some fairly irrelevant stuff) gets a little fussy, and the music doesn’t have enough space to do what it does best — namely, to work its little miracles unmediated by having people charging around all the time.

These operas are always an intricate dance of the shifting loves and loyalties of the principals

The forthright overture — a showpiece for Handel’s new star oboeist — gives us a dumb-show of mafia types, promising some bloody conspiring and betrayal. The action starts with a bang with the accession of Anastasio, sung with trumpet-like blaze by Keri Fuge. Our mezzo Polly Leach, singing Giustino, has a more giving tone, getting a good run-out in the first aria where the peasant has falling-asleep fantasies of glory before the dream appearance of the goddess, sung by Esme Bronwen-Smith, who doubles as the bear-victim Leocasta and has a lovely low alto. Mireille Asselin’s Arianna gets a lot to do and handles it all in a really serene style. Things are spiced up by the appearance of the baddie Amanzio, performed with a lot of jovially malevolent energy by Jake Arditti, and then the rebel soldier Vitaliano — luxury casting with top Handel tenor Ben Hulett. But the power-jockeying is of less interest to the director than the aching hearts of these tough cookies, with Anastasio in particular tormented by visions of Arianna and the jumped-up shepherd getting chummy.

These operas are always an intricate dance of the shifting loves and loyalties of the principals, and Hill-Gibbins cleverly builds up the layers in his psychological staging — and gives us a couple of monster-related jokes too, which is nice. While there’s plenty of movement and inventive ways of having something happening on stage — at one point involving a bunch of swinging lights, nice to look at but not very dramatically useful — actually a bit of stillness, and some relaxation in the hard-driven band, would pay dividends: most of Handel’s really deep, serious work is done in slower, reflective arias, and here everything feels relentlessly pushed on. The preposterous story hardly matters, though it feels a bit of a shame that nice Giustino turns quite so monstrous at the end. Things are wound up very briskly, and it’s all a bit pat. There are no great lessons or massive human revelations in Giustino, unlike most of what Handel wrote — but nobody’s about to complain about a couple of hours of fairly determined entertainment.

Runs until October 18th