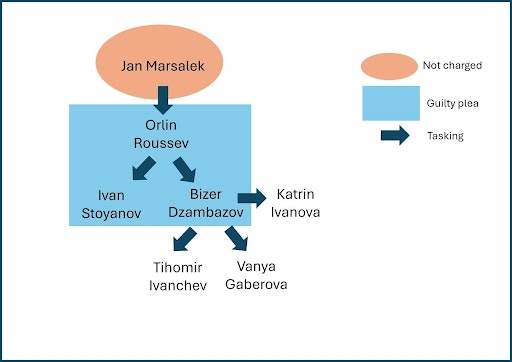

This month at the Old Bailey, a judge sentenced six Bulgarians to a total of fifty years in jail. Three had pleaded guilty to passing information to Russia in breach of the Official Secrets Act following their arrest; the others had spent months claiming they knew nothing of the plot. There were four men and two women, both in love with the same man. There were six operations, including plots to kidnap and kill investigative journalists, the surveillance of a US military base in Germany, and a sabotage attack on the Kazakh embassy in London. The ringmaster was Jan Marsalek, the disgraced Wirecard fraudster now allegedly working for Moscow.

Behind the soundbites was a strange, and rather sad, story

The drip-feed of details kept the press, lawyers, and jurors entertained over three months of hearing evidence. It was like something from a bad spy movie — the seaside hotel stuffed with secret gadgets, the plot to find “twin blondes” to seduce a journalist who wasn’t interested, the martial arts fighter nicknamed “the Destroyer,” and my own favourite — the community classes run by the spies on “the culture and norms of British society.” Yet behind the soundbites was a strange, and rather sad, story of a group of people who blundered through the instructions of a foreign state with strikingly little personal incentive to do so; ruining the lives of their victims and their own lives in the process.

It’s a story that shows how espionage is changing across Europe, the lines between state actors and amateurs increasingly blurred.

Orlin Roussev was the leader of the Bulgarians — allegedly taking orders from Marselek in Moscow. There was a hierarchy. The court heard how Biser Dzambazov and his long-term partner Katrin Ivanova first met Roussev at East Croydon train station in 2012, and went for dinner at a “posh” restaurant by the Thames. Ivanova said that as a newly-arrived immigrant, Roussev’s lifestyle impressed her. Lab assistants Dzambazov and Ivanova let Roussev store computers and equipment at their flat, with Roussev paying part of their rent. Over time, the favours that the pair carried out for Roussev drifted into criminality. They used false identity documents, primarily for the purposes of banking. Others were recruited by middleman Dzambazov — his mistress Vanya Gaberova, and Gaberova’s ex-boyfriend Tihomir Ivanchev. They travelled to different European capitals and met with Russian agents. Ivanova, who got nine years and eight months, ended up driving around an army base with a police-grade device, listening for messages from Ukrainian soldiers.

“You threw in your lot with him [Dzambazov]” the judge told Ivanova, “For better, or worse.”

Historically, the KGB and FSB took great pains to train Russian deep-cover agents, who were often married couples working in pairs. The dynamic was tightly controlled; spies were banned from speaking Russian to each other even inside their own homes. The recruitment for the Bulgarian operation — the largest on British soil in recent years — was much more casual, with only Roussev working directly for the FSB. It appears that the expansion of the cell (further recruitment) was allowed to happen organically, with those at the top exploiting the existing dynamics you would expect in a group that included friends, colleagues, lovers, and rivals — jealousy, ambition; and at times, the skilled cooperation born of familiarity.

The hierarchy was manipulative, and some decisions regarding the women may have been made over their heads (the much-quoted “honeytrap” did not go much further than a discussion between Roussev and Marsalek about Gaberova’s availability for sexual services.) But the text messages proved that by the end of the operation, even those at the bottom knew the true identity of those at the top.

This case gave a window into Russia’s transnational repression of citizens of a third state; namely, Kazakhstan. “Operation 3” (where the Bulgarians were tasked with following a Kazakh politician living under political asylum in the UK) and “Operation 4” (a plot to stage fake protests at the Kazakh embassy) had the same end goal — controlling Russian diplomatic relations with Kazakhstan, to Russia’s benefit.

The victim, Bergey Ryskaliyev, was the former governor of an oil-rich region in the west of his country. He explained his position to the prosecution:

“I am opposed to President Putin as I believe Russia and Russian influence is a hindrance to Kazakhstan. I cannot imagine freedom in Kazakhstan whilst Putin is in power. Most of Kazakh land borders with Russia and there is a lot of infrastructure in common.”

We already knew that FSB agents target foreign dissidents; sometimes cooperating directly with the intelligence services of authoritarian regimes in Central Asia in return for information on Russian dissidents living abroad. More remarkably, this case revealed the precise sums of money offered by the FSB to foreign amateur spies in exchange for acts of sabotage. Jan Marsalek reportedly told the leader of the Bulgarian cell that the “budget” for testing fake blood to be thrown at the Kazakh embassy was £3600. There was talk of giving Katrin Ivanova a monthly retainer of £2400. Payments of £300-400 a day were allocated for taxi-drivers in London. Moderate sums changed hands throughout the timeline of this case. Roussev’s ill-gotten gains were significant — he was ordered to repay over £180,000 to the court. The Bulgarians’ motivation appears to have been financial — and up to a point (Gaberova took selfies in her RayBan spy glasses) because they found it exciting.

The Bulgarians tried to downplay their knowledge of Russia when giving evidence. However, there is little indication that the low-ranking spies knew about Kazakh domestic politics, or had any interest in acting against Kazakhstan. Russia-linked figures were nonetheless able to recruit them in London, and hold their interest through payments. It is possible — probable — for Russia, or another hostile state, to “outsource” more “freelancers” to replace those now in jail. This model of spying is now being taken seriously by the UK, as the judge’s final words made clear. Quoting a national security advisor, Justice Hilliard said it was “important that the UK was seen as a safe place for those fleeing persecution,” with Russia now seen as “the number one threat” to security.

Vanya Gaberova was sentenced to six years and eight months in prison. Minutes before the judgement, the defence attempted a mitigation for the 30-year old beautician. My client was a naïve young woman from a small town in Bulgaria, said Mr Metzger KC. She was “besotted” with her lover, Bizer Dzambazov, and had no training as a spy. She made no “management decisions.” Gaberova, in the dock, cried when she saw her mother and sister in the public gallery. Metzer described her life at HMP Bronzefield — suffering from claustrophobia, assaulted on her way to court, unable to receive visitors. He drew attention to her “undoubted, internationally recognised skill with eyelashes.” The last line got some laughs — although it was evident that the seizure of her small business in West London and the firing of her staff was distressing for Gaberova. Unlike Roussev’s hotel in Yarmouth, it is not thought that the beauty salon was a front for crime.

Sabotage cells continue to be uncovered in the UK, linked to Russia, and to Iran

The judgement — and the careful weighting of sentences — acknowledged that two things could be true: a naïve spy could be groomed by her partner and drawn into a conspiracy that went beyond her control, and she could be an active participant who made choices that damaged people’s lives. The court heard from Christo Grozev, one of the journalists stalked by the spy-ring. Grozev, 55, also from Bulgaria, has been living apart from his family in an undisclosed location since the events of the conspiracy.

“It was terrifying, disorientating, and destabilising,” said Grozev. “For me and my family the damage is ongoing.”

It could be argued that the conditions of self-imposed house arrest are not dissimilar from prison.

Sabotage cells continue to be uncovered in the UK, linked to Russia, and to Iran. This week, three Iranian nationals appeared in court, over a plot to carry out a violent attack on an exiled Iranian TV station at the behest of Tehran. A series of parcel fires targeting courier companies in Britain, Germany and Poland has been traced to Russian intelligence. And details are still emerging about the recent fires in properties linked to Kier Starmer. The aim of sabotage operations by hostile states is to weaken those perceived by the state as the enemy, and to sow chaos and discord. Often, those who commit sabotage are low-ranking “disposables.”

The bizarre details of the Bulgarian trial felt unique — but the use of an existing group hierarchy, the attacks against a third state, the careful structuring of payments, and the recruitment of low-paid immigrants by others in their social circle are all part of a wider pattern of casualised espionage. It could happen again. Counterterrorism police reduce attacks by understanding radicalisation as a form of grooming; espionage can begin in a similar way. Recognising the patterns could help future Gaberovas and Ivanchevs to be identified before they are drawn into the web.