What if a rogue AI impersonated a child and had sex with another child — a real one this time — while both were dressed as animals in a virtual reality chat room? Would it be rape? Child sexual exploitation? Is there a bestiality element to consider? Who gets sued — the VR platform? The AI company?

This was not a scenario I had given any thought to until I was sitting on a roundtable with some of the finest legal minds in the House of Lords, going over the umpteenth round of changes to the Online Safety Act (OSA).

Since the release of its white paper in April 2019, the legislation — then in draft — had been overseen by eight Secretaries of State, three Prime Ministers, and two different sponsoring departments. Everyone involved wanted to leave their mark.

The resulting 303-page Act, and the thousands of pages of codes of conduct that accompany it, is a quite remarkable piece of legislation. Remarkable because it sacrifices both freedom of expression as we know it, and Britain’s hopes of sustaining a world-leading tech industry to protect the innocence of a theoretical child in Tunbridge Wells.

Yet the story of the OSA is interesting, and tragic, not just because of this law, shockingly bad though it is. It also shows, yet again, how very badly we are governed.

Many ministers would tell you — with much elation — that the OSA was exciting because it was the first law of its kind. Countries across the world would be looking to us as a leading example!

But it turns out that pioneering comprehensive regulation of the internet when you don’t actually really understand the internet is not exactly best practice. With nowhere to look to understand what worked — and, crucially, what didn’t work — campaigners and policy experts attempting to argue that certain elements of the Bill would have awful unintended consequences had few case studies to point to. So their warnings about the risks were simply not accepted.

It was also terribly sad, but perhaps emblematic, that one of the first things we aimed to do independently post-Brexit was to add even more regulations to one of our fastest-growing sectors — particularly since the people making the rules barely understood what they were regulating. In one policy meeting I attended, senior figures spent a significant length of time debating whether the internet was more like a town square, or a café where the owner decides what patrons can discuss. They had no coherent mental model for what the internet actually is, let alone how platforms function. In 2023, when the then Digital Secretary Nadine Dorries arrived at a meeting with Microsoft, she asked when they were going to “get rid of algorithms”.

This ignorance was exploited by campaign groups, often founded in deep and legitimate grief. The Molly Rose Foundation, for example, was set up in 2017 following the tragic loss of Molly, a 14-year-old who died from self-harm after viewing harmful online content. The organisation initially focused on suicide-related content, which made sense. However, it is now lobbying on the automation of risk assessments, the data implications of US trade deals, and the economic case for a stronger OSA, having cemented its position as a group governments simply cannot go against.

Indeed, where children were involved, many MPs and peers simply lost all perspective. Comments were routinely thrown around about it being worth tech companies going bust if one child was saved, even if many of the children being “saved” were totally hypothetical edge cases, such as victims of AI-impersonated children in virtual reality chat rooms.

The legislation that emerged is, accordingly, staggeringly vague. Section 2’s definition of “content that is harmful to children” encompasses anything that presents a “material risk of the content having, or indirectly having, a significant adverse physical or psychological impact on a child of ordinary sensibilities”. This circular non-definition essentially asks platforms to divine what might upset some theoretical average child — a standard so subjective it makes consistent enforcement impossible.

From the beginning, campaigners — such as the Centre for Policy Studies, where I work — warned that this would have unintended consequences. Faced with such vagueness, platforms would inevitably err on the side of caution, especially given fines which can reach £18 million or 10 per cent of global annual turnover, whichever is higher. Even more pernicious are the provisions on director liability: senior executives can face personal criminal sanctions, including prison sentences, for failures in their companies’ child protection systems. Why would any Silicon Valley executive risk establishing a UK presence when an algorithmic miscalculation could land them with a £13 billion penalty, or a spell in jail?

The result is that, if a 12-year-old somewhere might find content about mental health, relationships or political topics distressing, the rational response is to remove it entirely rather than risk regulatory action. This hands enormous discretionary power to Ofcom, which must somehow translate Parliament’s woolly concepts into concrete rules. When legislation is this imprecise, the real law-making happens not in Parliament but in the offices of civil servants, quangos, and tech companies’ compliance departments. If we have any tech companies left.

Many policy experts have recommended a clearer approach: create tough enforcement against content that is already illegal, while requiring any new speech restrictions to go through full parliamentary debate rather than being decided by regulators. The Centre for Policy Studies, for example, has argued that if the government isn’t prepared to make certain speech criminal through a proper democratic process, it shouldn’t punish platforms for hosting it.

This is a government blighted by data leaks, demanding access to some of the most sensitive intellectual property in the world

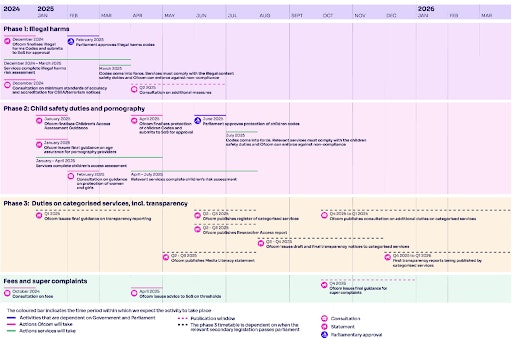

Already, we are seeing the pernicious effects — as campaigners warned, much legitimate speech is already being suppressed as a result of the legislation. Yet this week’s furore over content blocking marks only the halfway point of the Act’s implementation. There remains a deluge of further duties and codes for e-commerce companies, which will then be followed by the highly controversial transparency obligations. These will mean that from next year, Ofcom will be able to require companies to provide any information about their algorithms and access internal documents, data, technical infrastructure, and source codes. This is a government blighted by data leaks, demanding access to some of the most sensitive intellectual property in the world.

The legislation was brought in under the Conservatives, but Labour has already signalled that this regulatory expansion will continue — indeed, its main complaint during the parliamentary stages of the Act was that it did not go far enough. Minister Heidi Alexander recently said the OSA is not the “end of the conversation” about making the internet safer. The pressure from children’s safety groups will only mount, and with a review mandated in 2028, just before the next election, there are obvious political incentives for even harsher measures to be introduced under the guise of saving the children.

What we have here, in other words, is legislation that was broken from conception to implementation. The Online Safety Act emerged from ministerial chaos, technological illiteracy, and a parliamentary process dominated by emotion rather than evidence. The result is legislation so vague that it hands sweeping powers to regulators while creating punishments so severe they will drive companies away from Britain entirely. The road to the erosion of our tech sector and digital freedoms has been paved with good intentions — and unforgivable incompetence