There is, we are told, a crisis in masculinity. Men and boys are falling – or being left – behind, and the statistics bear this out.

Since the pandemic alone, for example, the number of males aged 16 to 24 who are not in education, employment or training has increased by a staggering 40 per cent, compared to just seven per cent of females.

Young women earn nearly 10 per cent more on average than their male peers, according to the Centre for Social Justice (CSJ) – and are 33 per cent more likely to go on to higher education.

Young men now spend more of their free time alone than any other group, have fewer close friends than ever before, and are disproportionately more likely to commit suicide. Perhaps most worrying of all is the soaring numbers of men who endorse a ‘red-pilled’ misogynistic ideology: anti-feminist beliefs prevalent in the so-called ‘manosphere’, that online community of angry men who believe that all their troubles can be traced back to female emancipation. The term ‘red pill’ comes from the Matrix films – and refers to one’s eyes being opened to a new and perhaps more dangerous way of thinking.

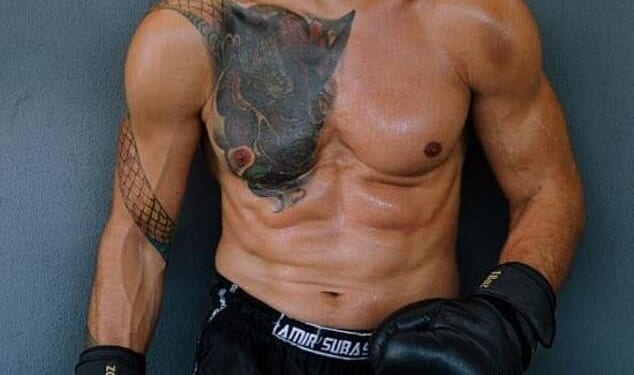

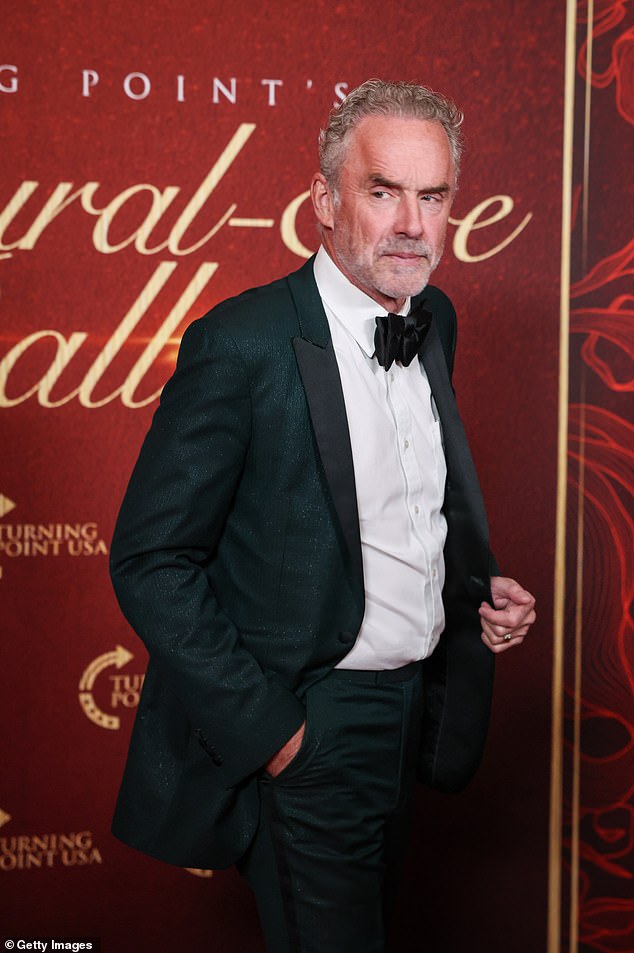

Endorsed and amplified by a influencers ranging from the thuggish former kickboxer Andrew Tate (currently under investigation for human trafficking, which he denies) to the more intellectually sophisticated Jordan Peterson, the central tenet of this belief system is that feminism has overturned the natural order of things by allowing women access to areas of society previously dominated by the male of the species, causing a crisis not just of masculinity, but also undermining traditional female values in the domestic sphere.

So what’s the truth? Has feminism truly created an awful backlash of male loneliness, lack of purpose, suicide, misery – and, at the edges, misogyny and violence? Or – yet again – are men just blaming women for their problems?

Thuggish former kickboxer Andrew Tate (currently under investigation for human trafficking, which he denies)

Jordan Peterson, who believes that feminism has overturned the natural order of things by allowing women access to areas of society previously dominated by the male of the species

Not all proponents of this ideology are even men. The Canadian YouTuber Karen Straughan, for example, espouses the ‘honey badger’ movement (an animal known for its aggressive nature) – that is, female men’s rights activists.

She argues that the pendulum has swung too far in women’s favour, and that men are treated as socially expendable by a world that does not appreciate their worth. ‘Modern feminism isn’t about women’s rights. It’s about women’s privilege,’ she says.

This may seem somewhat ironic, given that without feminism she would very likely not have the platform she has – but logic and reason are not necessarily overriding features of the manosphere.

Fortunately, there are other, more reasonable voices in this area. One such person is Scott Galloway, Professor of Marketing at NYU Stern Business School and host of the Prof G podcast, whose new book, Notes On Being A Man, sets out an entirely different set of propositions.

He doesn’t deny that there is a problem here, but he believes that manosphere figures such as Tate are exploiting this crisis for their own gain, targeting vulnerable men and boys and encouraging them towards women-blaming and other toxic behaviours.

He argues, rightly, that this is not just a male issue, that women and children can’t flourish if men are not thriving. As he points out, there is nothing more dangerous than a ‘lonely, broke young man’, and we have all seen that played out tragically in recent years.

His book sets out an alternative path, a kind of manual for the modern man, based on his own experiences growing up. It’s an emotionally intelligent, non-toxic take on how both men and women can reset the relationship between the sexes in a post-feminist world.

He asserts that masculinity is not about dominance – it is about resilience, doing the right thing, establishing meaningful connections in life and learning to maintain them.

He urges boys and men to choose agency over victimhood and blaming others (women in particular) for their woes. He posits the idea of the ‘three Ps’ – protecting, providing, procreating – as a recipe for healthy, fulfilling masculinity.

As the mother of a 20-year-old young man who is still finding his way in life, I found this book not only fascinating, but deeply uplifting.

I live with both my adult children, and I see first-hand the differences in attitude and ambition between my son and his elder sister, who is 22.

When I observe them with their friends, there is a marked difference between the boys and the girls. The latter are outgoing, confident, self-assured in a way that my generation just never was at that age.

The boys, by contrast, are far less dominant than they were in my day and tend to retreat more readily into what I would term their ‘safe spaces’, namely internet gaming or playing football.

I hate to say it, but their interests seem fairly narrow compared to those of my daughter’s cohort, and when I speak to them about their plans in life, their ambitions are modest despite their educational achievements.

There is a feeling of deep insecurity and uncertainty, and a lack of purpose and energy despite their youth.

It’s not born out of laziness, more a sense that whatever direction they try to take in life, their path will be thwarted. It’s not so much that they’ve lost their mojo – as never found it in the first place.

But interestingly, none of them blamed women or girls for this. Their worries were far more centred around failure of government, the mistakes of the pandemic, social inequality, the lack of training or job opportunities and the threat of AI.

They didn’t seem to feel that women had any less right to succeed in life than they did, simply that there were fewer opportunities for their generation all round.

That might have something to do with the fact that many of them – more than I would have expected – have mothers who are quite strong role models, very often not through choice, but by necessity. Many of them come from families where the main carer/breadwinner was the mother, and several have little or no contact with their fathers.

When we come to examine the causes of the crisis in masculinity, I think the role of my generation of men must also be considered.

Put bluntly, many of them tried to have their cake and eat it. They enjoyed the fruits of the sexual revolution – no-strings relationships, women being expected to pay their own way and so on – without any of the responsibilities expected of their fathers.

They saw women’s liberation as an opportunity, and they exploited it, often cruelly. They liked the fact that they weren’t the only ones now expected to pay the mortgage, go out to work or pay for dinner.

Women now shared not only their opportunities, but also their obligations. Plus, of course, the added burden of bearing children.

So many of the women I know have had to step up where the men have not. As a result, my generation of women is arguably one of the toughest and most capable there has ever been, since we have no excuses and nowhere to hide if we can’t take care of ourselves. That is the price of feminism.

I, for one, am happy to pay it. But there are many who are not, and they aren’t just men.

Hannah Neeleman, aka ‘Ballerina Farm’, has eight children and lives on a rural farm in Utah (although they recently spent several months in Ireland, to attend the prestigious Ballymaloe cookery school)

Social media is awash with Stepford Wife type influencers, popping out adorable infants in between nursing their sourdough starters and massaging their husbands’ egos.

These so-called ‘trad wives’ wax lyrical about how empowering it is to do their family’s laundry by hand while cosplaying as 1950s housewives – and in some cases are so outlandish you think they must be parodies.

Not so. Hannah Neeleman, aka ‘Ballerina Farm’, has eight children and lives on a rural farm in Utah (although they recently spent several months in Ireland, to attend the prestigious Ballymaloe cookery school) and thrives of home birth, bread-making and cleaning.

And Nara Smith cooks complex meals from scratch in her couture gowns while purring into the microphone like a Seventies sex kitten.

There are countless others like them on the internet, all portraying a version of femininity that for most women only exists if you look like a supermodel (as they both do) and marry a rich man (as they both have).

They are the yin to Andrew Tate’s yang, and as such arguably no less toxic in terms of the expectations they create while at the same time monetising people’s insecurities. Don’t get me wrong, I have some sympathy for the plight of the modern Western male who in this post-feminist, post-MeToo world finds himself stripped of the supreme status enjoyed by his gender for thousands of years.

It must be tempting to look at his brothers elsewhere in the world, many of whom still exercise iron control over the female of the species, and think, ‘why me’ and ‘where did it go wrong?’

Because let’s not forget, this is essentially a first world problem.

No one would argue that there’s a crisis of masculinity in, say, Afghanistan, where men rule supreme and girls and women are banned from all aspects of public life, including education and basic healthcare.

Nor is it evident in Iran, or among those who carried out the attacks of October 7, or those currently setting fire to maternity hospitals in the Sudan.

Where are the feminists in Afghanistan? In Iran, Syria? Where are they in Africa, in countries like Somalia and the Yemen, where child marriage, FGM and rape are rife? Let’s talk about the Congo, or parts of South America like Colombia, Mexico and Guatemala.

I don’t see many Betty Friedans or Germaine Greers there, do you? There has been no comparative women’s liberation movement to the one in the West in any of these places. They are run, as most of the world has always been, by men. Feminism has not driven them to violence, they’ve developed their toxic masculinity all by themselves, bless them.

Nara Smith cooks complex meals from scratch in her couture gowns while purring into the microphone like a Seventies sex kitten

So don’t talk to me about how feminism has ruined things for men. That’s nonsense. What it has done is allowed women to grow and flourish in ways previously denied them.

And that, I can see, might be a problem if you happen to be the kind of man who can’t cope with the idea of a woman having agency over her own life. Or doing his own laundry.

Instead of accepting that their entire success or failure should be dependent on obtaining the approval of a male, feminism gave women the hope that they might be worth something as intrinsic human beings in their own right.

On the surface of it, that does not seem like an unreasonable request. And yet it is being blamed for a generation of men who feel angry, dispossessed, marginalised and undermined.

It’s fuelling a rise in so-called ‘incel’ culture, and creating an epidemic of male depression and other mental health issues, poor educational and economic outcomes, a fundamental dysfunction that manifests itself in a variety of ways, from drug use to porn addiction.

I hate to say it, but this is such a typical male response – as any woman who has ever experienced domestic violence or been the victim of coercive control will recognise.

‘Look what you’ve driven me to, look what you made me do!’ they say, as they stand over you with fists raised, or as you silently, shaking, pick up the pieces of the broken bottle or plate aimed at your head. You wore the wrong thing, you said something out of turn, you overcooked his steak.

You, you did this. Not him, not his rage, not his fist, not his insecurity, not his entitlement. It’s your fault. You, woman, drove him to it. If you just knew your place, none of this would happen.

This is and always has been the story for women, ever since Eve took the rap for that nasty business in the garden of Eden. It’s what informs the abuse of women and girls all over the world, as they are beaten, raped, killed for failing to comply with the rules imposed upon them by men too insecure to realise that a woman’s power does not need to negate their own.

I don’t denigrate or deny the problems young men face today. But I would say this: none of what they are experiencing is unfamiliar to girls and women – it’s just that we are far more used to it than they are because of the way society has, traditionally, treated us.

Women have levelled up. It’s time for men to stop endlessly complaining about it – and do the same.