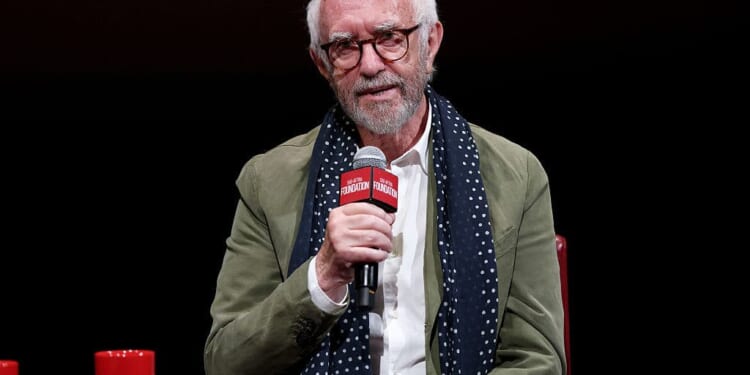

Despite (and often because of) their many odd ways, I like actors. You might reckon that’s a good thing for a playwright. I usually get on with them, and the talented ones are like gold dust. But too often I read an interview with one of the profession and hang my head in despair. The folly is heartbreaking. It’s worse when it’s an actor whose work you admire. So it is this week with Jonathan Pryce. Pryce has opened his mouth — predictably, to The Guardian — and declared that a TV or stage drama about refugees could “defuse anti-migrant anger” by humanising their experience. This, as the Guardian’s Lanre Bakare glosses, could be “one way to defuse the rising anger and anti-migrant sentiment in the UK.”

Pryce explains, as if it were a revelation, that drama is a tool for empathy and education. He contends that much anti-migrant sentiment is built on ignorance — that people simply aren’t aware of the everyday dilemmas faced by displaced people. He draws on his own experience in Hotel London (1987), an obscure, largely forgotten low-budget drama depicting a South Asian family evicted into homelessness, living in cramped accommodation, and enduring prejudice. Pryce lectures that politics, protests and news coverage often focus on the “front stage” — immigration debates, statistics, border policy — but rarely show the interior of a hostel, the conditions of migrant hotels, or the emotional burden carried by those inside. Drama, he thinks, should push into those hidden spaces. The underlying donnée is that if people only saw the lives of migrants, their anger would dissolve and a warm-hearted feeling would spread like the Ready Brek glow through the minds of the hitherto hostile audience.

There’s another donnée here: a presumption that beneath all the antagonistic coverage and tabloid myths, migrants — all migrants, it seems — are people we would, if we only knew them, welcome with open arms. This gives us a clue to how they might be characterised in Pryce’s putative drama: good people who only want a better life, and who are, as per Fred and Wilma Flintstone, “just like you and me.”

This we might call the Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner tactic. In Stanley Kramer’s classic liberal “message picture”, a decent and liberal middle-class couple (played with award-deserving straight faces by Spencer Tracy and Katharine Hepburn) are shocked to discover that their daughter’s fiancé is a black man. After much exposure of initial bias and soul-searching, Ma and Pa eventually realise that the only thing that truly matters is how much the young couple loves each other. The film relies on legerdemain. Played by the handsome Sidney Poitier, the prospective son-in-law is coded as an ideal and exceptionally accomplished man in every respect — highly educated, internationally respected, impeccably mannered, morally upstanding, strong and self-assured. The parents would have to have white robes and conical hoods stashed in the closet not to embrace him.

The Poitier model is, I guess, how the migrant Pryce wishes to bring to our dinner tables will be characterised. Possibly he will be highly trained and a perfect fit for an occupation where we have a skills shortage. At worst, he will be a thoroughly decent chap who simply wants to settle down and do a day’s honest work for a fair wage. The only things against him are the pesky systems the British state puts in his way as he attempts to resettle in this country. By the end of the viewing, the audience — like Tracy and Hepburn — will have had their prejudices challenged and their hearts and minds opened. They will never look at a migrant with hostility again.

Pryce’s view of the indigenous population is strikingly narrow

The trouble with the Poitier model is that it’s rather rare to meet anyone so perfect in real life. Although Pryce wants his drama to counter negative media coverage, much of that coverage — especially on social media and in the non-Guardian press — has already made the “ignorant” people he wishes to enlighten aware of migrants who would be rather less attractive dinner guests or sons-in-law. I doubt that Pryce imagines, as his protagonist, a migrant like Hadush Kebatu, found guilty in September of two sexual assaults, one on a fourteen-year-old girl. Nor would he feature one of the “skilled” migrants who make public displays of antisemitism, or those banned from practising in their countries of origin. Such a character might not have the desired effect — but if the drama refuses to acknowledge such cases, it will surely be scoffed at by the very audience it is meant to persuade.

Pryce’s view of the indigenous population is strikingly narrow; the British appear only at the edges — as the noisy protesters or the well-meaning activists. The learning he envisages is very much a one-way street. British audiences will be educated about the difficulties migrants face when seeking asylum in their country — but would any migrant watching learn about the lives and concerns of British people: the unease over the enormous cultural change migration brings, the anxieties about strains on social services and housing, the fears of women and girls who are harassed or, in the worst cases, assaulted by migrant criminals? There may be arguments that some of these qualms are exaggerated or wrongly directed. But to dramatise a wide survey of the failures of social planning would demand a far bigger project than the low-budget indie film Pryce offers as his model.

Pryce sees his drama taking us “inside the hostel or the hotel where they are, and the conditions in which they’re living.” No doubt conditions in some HMOs are unpleasant — though we also know that some of the hotels housing migrants are four-star establishments. Does Pryce imagine that every British citizen lives in the kind of comfort that multimillionaire stage and screen stars enjoy? We might all agree, after watching his migrant drama, that being stuck in a holding pen with strangers united only by asylum status would be grim. But such empathy tells us nothing about migration per se. It would also provoke a shrug from anyone in the audience living in poor accommodation, without their bed and board paid and with no free taxis to an NHS doctor. Pryce appears to believe his entire audience resides in Hampstead Garden Suburb.

Didactic drama is fiendishly difficult to pull off — even if one thinks it a worthwhile use of the form in the first place

Everything in the interview suggests that Pryce sees drama as a didactic exercise in educating the ignorant. Such a dramaturgy depends on cherry-picking and on two presumptions: first, that people are ill-informed and that this ignorance leads them to lack empathy; second, that once their minds are opened by a viewing, a complete change in attitude will follow. Yet didactic drama is fiendishly difficult to pull off — even if one thinks it a worthwhile use of the form in the first place.

Brecht, the twentieth century’s most persistent practitioner and theorist of didacticism, struggled to make audiences feel what he thought they should. His 1940 play Mr Puntila and His Man Matti sets out to show how Puntila, the aristocratic landowner, is a rogue — genial when drunk, selfish when sober — while his chauffeur, Matti, is the model of an upstanding proletarian. Yet in performance, Puntila, precisely because of his contradictions, comes across as the more human and sympathetic figure, and Matti as a rather dull churl.

Any attempt to reduce the complex and multifaceted problem of migration — perhaps our age’s most intractable social question — to a simple lesson in brotherly love will be seen through instantly by audiences already well aware of how wannabe social engineers rig drama scripts to score their political points. Mr Pryce is a brilliant actor — the finest Hamlet of his generation, always compelling whether in Albee or Game of Thrones. That does not make him a compelling thinker, and on the evidence of this interview, he risks damaging both his own reputation and that of his profession by peddling such simple-minded and frankly patronising pieties.