Children and schools are suffering as a result of the imposition of VAT on private school fees

The government’s projections regarding the imposition of VAT on private school fees are now being exposed for what they truly are: ideologically driven assumptions, lacking both financial rigour and practical foresight. Out by a factor of four.

For months, the public has been told that ending tax exemptions for independent schools would generate £1.8 billion annually by 2029/30 — funds earmarked to recruit 6,500 new teachers and raise standards in the state sector. Labour spun it as “ending tax breaks for private schools”. Yet this narrative was built on deeply flawed modelling as well as electoral spin.

Behind closed doors, the political calculus was clear. The policy would serve dual purposes: increasing state control over education and weakening the independent sector. It was framed as a justified tax on the wealthy for the majority, a populist move in austere times. The catch was that not only “the rich” send their children to private school, as they well knew. It seemed excusable to ignore the collateral damage of the low-to-middle income parents of pupils with special needs who were being abjectly failed, or the religious parents refusing to have LGBT Pride teaching and celebration enforced on their child. There are so many like them.

The public framing still ignores the reality that many families are making incredible sacrifices to educate their children privately, and were far from wealthy. The government predicted an average fee increase of approximately 10 per cent. However, the actual average increase reported by the Independent Schools Council was 22.6 per cent in the year to January 2025. Another miscalculation.

Families are now, evidentially, being priced out of private education. The imposition of VAT, alongside the removal of business rates relief and increased National Insurance obligations, is pushing many low-cost private schools to the brink. As closures mount and pupils migrate to the state sector, the financial burden on the Treasury increases — not decreases.

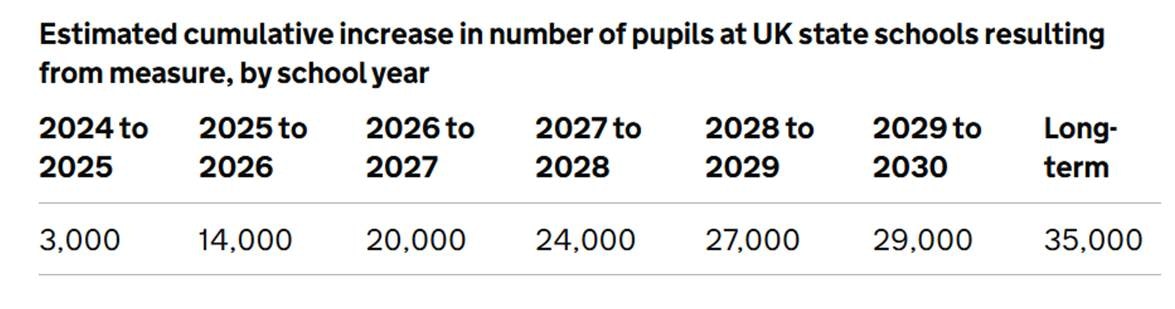

The government’s own estimate, published in November 2024, suggested that only 3,000 pupils would leave the independent sector by the end of the 2024–25 academic year. Yet recent data from the Independent Schools Council, representing only 80 per cent of the sector, shows a decline of over 13,000 pupils in the year to January 2025. Numbers had dropped from 551,578 to 538,215. This is more than four times the official forecast — and the full impact is likely yet to be felt.

Parents do not make sudden decisions about the education of their sons and daughters. Many are only now beginning to calculate the long-term affordability of private education under the new tax regime. As more families reassess their options, the exodus is likely to accelerate.

If the government’s long-term forecast of 35,000 pupils leaving is similarly underestimated by a factor of four, the true figure could easily exceed 150,000. At an average cost of £8,000 per pupil per year to the state, this would represent an additional £1.2 billion in public expenditure — eroding the very revenue the policy was intended to raise. Additionally, the number of families who will actually pay the VAT will be lower than anticipated, further diminishing the projected £1.8 billion supposed windfall for the state system. The Adam Smith Institute predicted that if there were a 10-15 per cent loss of pupils, around 60,000 pupils, from the private sector to state schools, the tax would generate no net revenue. In a 25 per cent migration scenario, their analysis suggests the tax could lead to a significant loss to the Exchequer of £1.58 billion!

Even if the promised investment could have ever materialised, it would amount to fewer than one additional teacher per school. This was never a serious solution to the challenges facing the state sector, let alone the increased demand it now faces due to the VAT policy.

Unless revised, this policy will continue to undermine both financial prudence and educational provision

The same flawed approach appears to have informed other recent Labour decisions, such as the winter fuel payment thresholds — policies that have already had political consequences in local elections. A correction is now being considered for pensioners. One must ask, will the same reconsideration be extended to education? Certainly, the extended pause on the findings of the Judicial Review on the very legality of the unprecedented VAT policy, suggests that the government may have made legal errors as well as financial.

Unless revised, this policy will continue to undermine both financial prudence and educational provision. The numbers do not support it. Nor, increasingly, will the public.