This article is taken from the June 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £25.

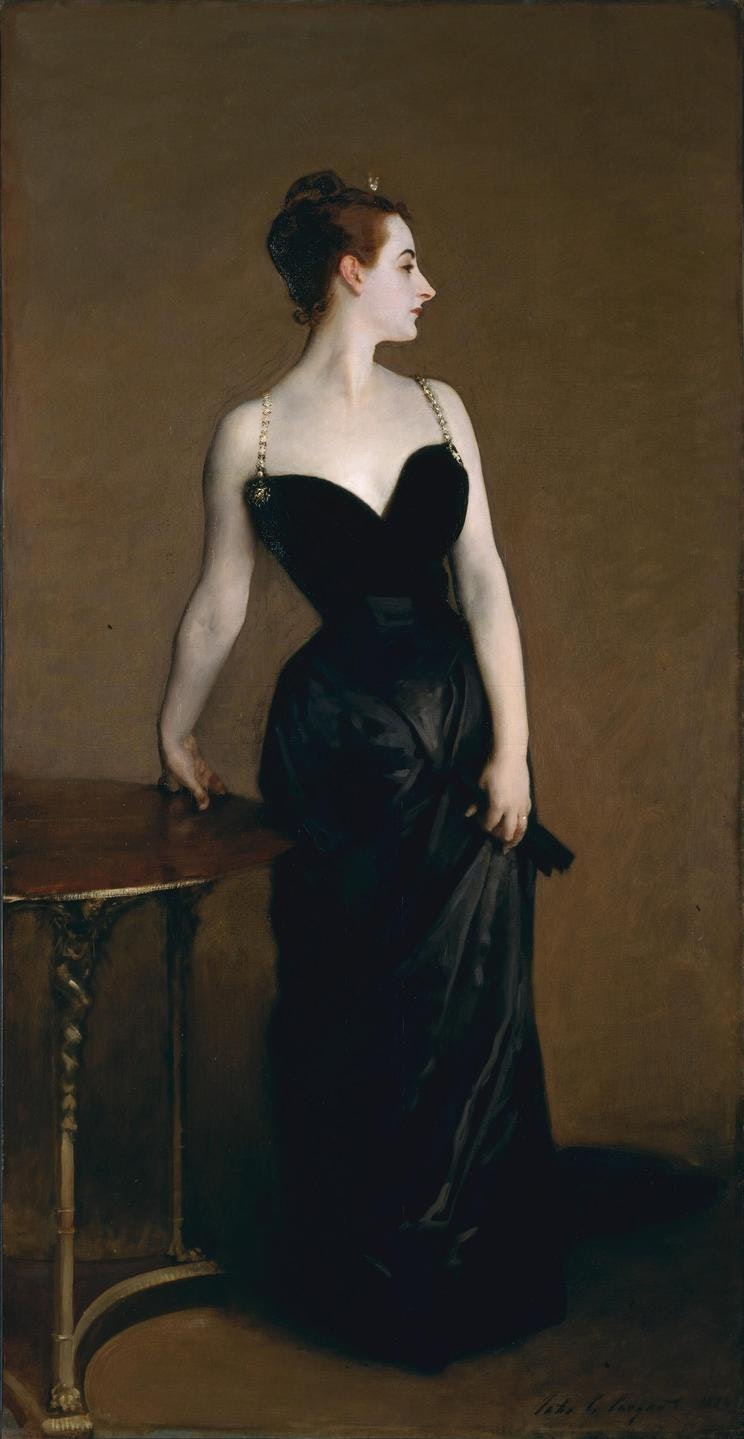

An alternative title for John Singer Sargent’s celebrated portrait Madame X (1884) might be, “Be careful what you wish for”. At the time of its painting, Sargent was an up-and-coming artist living in Paris who had already exhibited at the Salon six times; Madame X was another expat, Virginie Amélie Avegno Gautreau, a New Orleans Creole who was one of the celebrated beauties of the Belle Époque. They both wanted something from a collaboration.

Sargent needed, he felt, a “statement” picture to establish himself fully in his chosen milieu, whilst “La Belle Gautreau” wanted a public image that would help disguise the fact that her husband’s money came from guano and ease the social restrictions resulting from her mixed-race heritage.

Amélie’s striking looks — hennaed hair, preternaturally pale skin which she made even paler with small doses of arsenic, ski-jump nose — readily caught the eye.

Another American artist in Paris, Edward Simmons, recalled that he “could not help stalking her as one does a deer … Her head and neck undulated like that of a young doe … Every artist wanted to make her in marble or paint.” Sargent was the chosen one.

Nevertheless, she was not the easiest of sitters. Amélie was fidgety and easily bored; Sargent complained of “the unpaintable beauty and hopeless laziness of Madame Gautreau”.

He tried to divert her with incessant talk about such topics as food, wrestling and ice hockey; he would chain smoke whilst painting and supposedly cover some four miles a day in stepping up to his canvas and back again.

Gradually, at her estate in Brittany, Sargent compiled a series of 30 preparatory works in pencil, watercolour and oil in which he tried out various poses.

The one he finally settled on was striking: full length, body turned toward the viewer, head in profile like a Renaissance medallion, minimal background or clutter, and a dress with a steeply curving heart-shaped bodice. “I suppose it is the best thing I have done,” the painter would later write to his longtime friend Edward Robinson, director of the Metropolitan Museum, when he was offering to sell the portrait.

Sargent put the painting up for sale because Amélie and her husband refused to buy it. The reason was the reception the portrait received at the Salon of 1884. There, Amélie was left, according to a witness, “slumped in a corner, she cried real tears” as she listened to visitors comment on the likeness.

What she had hoped would be a confirmation of her striking looks and social cachet turned into a disaster. The painting was exhibited as Portrait of Mme *** but the Parisian art-going public knew exactly who it represented and was scandalised.

Here was a married woman exuding an unmistakable sexual charge, her figure and flesh unequivocally tactile, a strap of her dress slipping off her shoulder acting as an invitation to indecency (Sargent would later repaint it in its correct position), the pose a frank challenge.

Sargent attended the opening day with Ralph Wormeley Curtis, who wrote: “I found him dodging behind doors to avoid friends who looked grave … I was disappointed in the colour. She looks decomposed. All the women jeer. Ah voilà ‘la belle!’ ‘Oh quelle horreur!’ etc … John, poor boy, was navré [heartbroken].”

The press critics were equally stern. The painting was “a wilful exaggeration” of every one of Sargent’s “vicious eccentricities, simply for the purpose of being talked about and provoking argument” (Art Amateur); “We are shocked by the spineless expression and the vulgar character of the figure” (L’Événement); “One more struggle and the lady will be free [of her dress]” (Le Figaro); “His portrait of the so-called beautiful Mme Gauthraut … is a caricature. The pose of the figure is absurd, and the bluish colouring atrocious” (New York Times); whilst one newspaper suggested that Amélie’s “sepulchral pale” skin would be perfect in an advertisement for a blackhead remedy.

The sitter’s distraught mother turned up at Sargent’s studio. “My daughter is ruined, and all Paris mocks her,” she wailed and demanded the painter remove the portrait from the Salon — he refused. In the event, Amélie took herself off into purdah in Brittany whilst Sargent decamped to England.

She would have her portrait painted two more times in an attempt to recover her reputation, but these pictures were barely noticed. It was said that in later life she had the mirrors taken down in her homes and that she would only go out at night-time.

Sargent’s career took the opposite trajectory. He eventually sold the portrait to the Met in 1916, a year after Amélie’s death. He stipulated that “I should prefer, on account of the row I had with the lady years ago, that the picture should not be called by her name.” And so it gained its name, Madame X. By then the picture was regarded as one of his greatest works and today it is the focal point of an exhibition at the Met, “Sargent and Paris”.

“Portrait painting, don’t you know, is very close quarters — a dangerous thing,” the painter once wrote. He meant the charged atmosphere of close proximity and the battle of wills between artist and sitter, but knew full well that the dangers extended beyond the studio.