This article is taken from the May 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Right now we’re offering five issues for just £10.

The publication of one book in Britain in the early 18th century scandalised and outraged the nation. It was a work which posed awkward questions, challenged assumptions about the nature of good and evil and even that of mankind itself. In the minds of many, it threatened to undermine and destabilise the very moral order of the day.

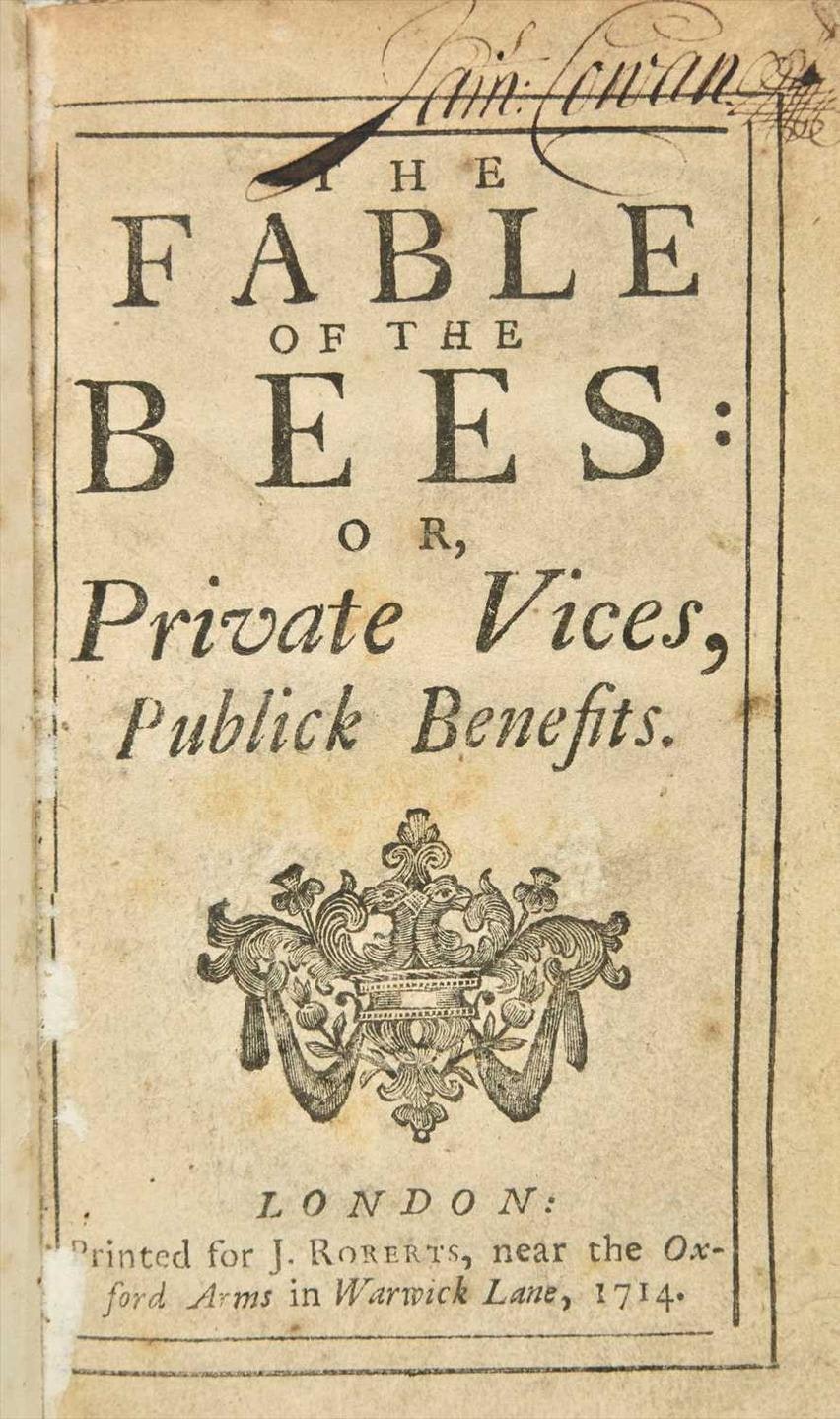

The book in question, The Fable of the Bees, was the handiwork of the Dutch émigré, doctor and pamphleteer Bernard Mandeville. Consisting of a long satirical poem followed by a series of prose remarks, reflections and essays, it imagined a hive of greedy and licentious bees who grow discontented with their lot. It’s not that their lives are marked by want. Like Mandeville’s adopted country, the hive functions well, being “happily governed by a limited Monarchy”, and its inhabitants are prosperous.

But such a state of affairs eventually arouses much envy and resentment, generating mutual denunciations of unfair and immoral gains and a wish that the hive could be improved and even perfected. Their god, tired and irritated by their canting complaints, grants the bees their wish and banishes overnight from the hive all immoral behaviour.

The results are catastrophic. With its occupants now devoted entirely to virtue, the economy of the hive collapses. Without crime, there is no need for police officers or builders to construct prisons. With no gluttony, no need for medical treatment or quacks. Without vanity, there is no fashion, no market for luxury goods or markers of conspicuous consumption. Without deception or conniving there is no need for lawyers to settle arbitration disputes. As the poem explains:

The Bar was silent from that Day;

For now the willing Debtors pay,

Ev’n that’s by Creditors forgot

Who quitted them, that had it not.

The doggerel which opens the book had first appeared alone in 1705, under the title “The Grumbling Hive”, and The Fable of the Bees was first published nine years later in 1714. But it was only after its reissue in expanded form in 1723 that the public was suitably ready to be appalled and offended.

The South Sea Bubble of 1720 had hit the pockets of ordinary men badly, and London was now awash with scribes and politicians decrying the avarice and libertinage of the new class of money-makers. This was no time to be making apologies for amoral, licentious, unfettered capitalism — and that is precisely what London’s literati took Mandeville’s handiwork to be.

Its pithy subtitle, “Private Vices, Publick Benefits”, attained an infamy of its own, and on 8 July 1723, the book was put on trial. The Grand Jury of Middlesex County Court was presented with a work deemed to “debauch the nation”, recognising no evidence of God’s influence or providence, one which sought to “run down religion and virtue as prejudicial to society … and to recommend luxury, avarice, pride and all kind of vices, as being necessary to public welfare”.

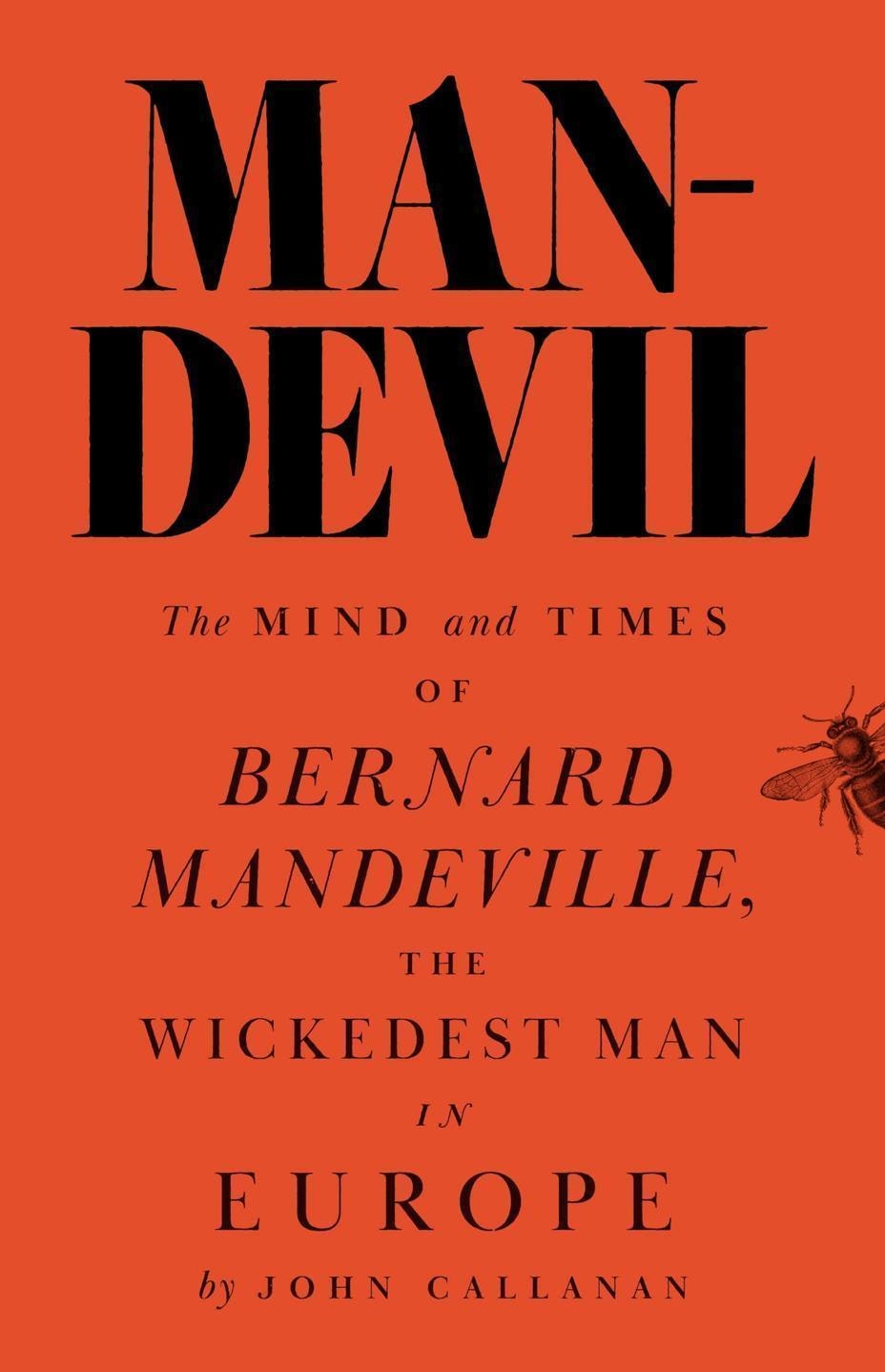

One anonymous poet captured the mood of indignation. “And if, GOD-MAN Vice to abolish came, / Who Vice commends, MAN-DEVIL be his Name”. The book’s notoriety spread to the continent, where the irreverent fable, translated into French and German, “turned Mandeville into one of the most influential thinkers of the eighteenth century”. So writes John Callanan, who adds that The Fable of the Bees was “propelled to a notoriety comparable to Hobbes’s Leviathan or Machiavelli’s The Prince”.

As satirists invariably discover, the public and cognoscenti often misunderstand the intent or point of their art. Here was a classic example. Mandeville’s work, certainly the opening poem, was not a prescriptive parable; it was merely one that spoke uncomfortable truths.

It didn’t contend that vice ought to be pursued. Its more modest, descriptive and anti-Utopian message was that vice is an inherent and permanent feature of the human condition and that immoral behaviour had the unintended consequence of tending to benefit the economy and society.

It was not that Mandeville approved of the pickpockets and prostitutes that proliferated in the London of his time, men and women who in their own way kept the economy afloat, the latter servicing the natural urges of men (his 1724 pamphlet, A Modest Defence of Publick Stews, argued in favour of legalised brothels).

He deplored the existence of criminals, but he also cast suspicion on the presumed virtue of society men: merchants, chemists, lawyers and medics. None of these were motivated purely by noble sentiments, he said, being animated instead by greed, self-aggrandisement and vanity.

Lawyers would defend those they knew to be law-breakers or just routinely fleece their clients. Doctors, eager to consolidate their exalted positions and mindful of the need to maintain demand for their services, kept ailing customers in prolonged poor health. Society demonised ne’er-do-wells, yet turned a blind eye to the dubious behaviour of “virtuous” men.

Britain accepted her merchants in their role of enriching the nation, yet didn’t condemn the scheming, dissembling and dishonesty intrinsic to their way of life. In this respect, Mandeville’s thinking anticipated Adam Smith’s economic theory of the Invisible Hand, a theme Callanan returns to. Mandeville, he adds, was later cited by Kant, Marx, Keynes and Hayek in developing our understanding of ethics and capitalism.

Yet the Dutchman’s unconventional take on morality also foresaw much of Friedrich Nietzsche’s thought — that “good” actions aren’t always motivated consciously or by benign intent or result in benevolent consequences. Mandeville deprecated the philosophy of the third Earl of Shaftesbury on the same ground that Nietzsche would come to malign Kant: for believing private probity and public virtue were the same thing and that the former necessarily leads to the latter.

Behind his curated image of mere pamphleteer and provocateur, Mandeville did set forth a serious ethical proposition, chiefly that contemporary morality and self-evident notions of “good” and “bad” are neither self-evident nor obviously good and bad.

This physician held that men were but animals, governed far more by “various Passions” than reason. What made humans unique was not their rationality but their refusal to admit that they were driven by unconscious desires, the foremost being a longing for superior status and the natural advantages it conferred. This impulse manifests itself in human society as pride and the yearning for the esteem of others.

Morality, and its attendant hypocrisies, was a way of repurposing and legitimising our instincts. Our notion of “virtue”, which might entail someone giving alms to beggars or bestowing largesse on new hospitals or schools for the poor to make them feel good about themselves, emerged to help us pursue our selfish instincts without reproach or condemnation.

Callanan, a philosopher at King’s College, London, has produced an engaging, expansive and effortlessly erudite study of a man who today too few people know. Man-Devil is a fascinating and welcome corrective, not least because Bernard Mandeville was amongst the first to argue that we don’t really know ourselves.