For locals in southern New Mexico and western Texas, the entrance of a new neighbor – the U.S. military – is stirring up a mixture of hope, distrust, and uncertainty. While some embrace more ways to deter unauthorized migration, others raise questions around the logistics and legality of new military zones.

More than 100,000 acres of federal land along the U.S.-Mexico border in this region has been transferred to the U.S. Army in what it calls new “national defense areas.” The military says it will detain people in these zones for trespassing, including unauthorized immigrants and U.S. citizens. It hasn’t detained anyone so far but has helped the Border Patrol detect over 150 unauthorized trespassers, a military spokesperson said. The creation of these zones is the first of its kind, and comes at a time when illegal border crossings are at their lowest levels in at least 25 years.

The development is part of a military surge directed by President Donald Trump since he declared a national emergency at the southern border on Jan. 20. It’s also emblematic of his whole-of-government crackdown on illegal immigration, forging partnerships across a variety of departments.

Why We Wrote This

Previous presidents have called the military to the U.S. southern border to support immigration agencies. The Trump administration’s novel expansion of the military’s role at the border raises legal questions and uncertainty among local residents.

Border Patrol encounters, a proxy for illegal crossings, swelled to record highs under the Biden administration along the southern border. Those apprehensions eventually fell following stepped-up enforcement from Mexico and narrowed access to asylum. They’ve plunged further – precipitously – as Mr. Trump’s illegal immigration crackdown creates harsher consequences, such as foreign prison cells, for those who cross illegally. April’s 8,383 encounters were down 93% from the same month last year.

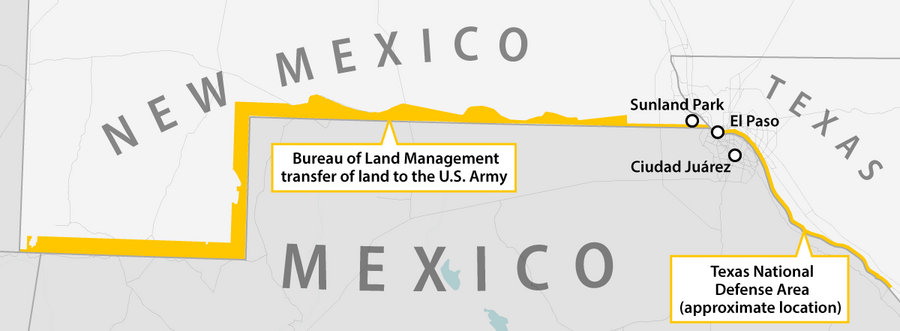

The Bureau of Land Management gave around 109,651 acres of federal land along New Mexico’s southern border to the Army in April through an emergency transfer. Gen. Gregory Guillot, commander of U.S. Northern Command, said the arrangement will “ensure those who illegally trespass in the New Mexico National Defense Area are handed over to Customs and Border Protection or our other law enforcement partners.”

Earlier this month, the military said a second national defense area was established in western Texas. Around 2,000 acres were transferred from the International Boundary and Water Commission, including part of the Rio Grande. Both transfers will last three years.

Using the military in this way to assist with immigration enforcement at the border “would be a first,” says Chris Mirasola, assistant professor at the University of Houston Law Center. Legally, he says, “The details here are going to matter a lot.”

The military’s new defense areas

Since 1878, the Posse Comitatus Act has generally prohibited the government’s use of the military for domestic law enforcement. Across Republican and Democratic administrations, military units have long offered support, like surveillance and intelligence, to immigration agencies.

The Trump administration’s creation of national defense zones along the border may be an effort to sidestep the law and militarize the border, critics say. The Department of Defense set up the new areas as extensions of preexisting Army installations in eastern Arizona and western Texas.

“The idea that the Defense Department can apprehend someone who enters into a military installation I don’t think will be susceptible to litigation,” says Professor Mirasola. What could attract lawsuits, he says, is “how much additional law enforcement activity the Defense Department undertakes.”

Joint Task Force-Southern Border personnel “do not conduct law enforcement operations,” Sgt. 1st Class Kent Redmond, a spokesperson for the operation, wrote in an email.

The first Trump administration explored military land transfers. The Department of the Interior gave some 560 acres along the southern border to the Army in 2019, for building border barriers. That land, however, wasn’t called a national defense area.

The term was first mentioned this April in a presidential action, in which Mr. Trump directed the takeover of certain federal lands by the Department of Defense. The Pentagon defines a national defense area as federal land over which it “maintains administrative authority and jurisdiction and is permitted to establish and enforce a controlled perimeter and access.”

The military says it has installed signs, in English and Spanish, warning that anyone entering the area may be detained and searched.

Asked by the Monitor for clarification of the national defense areas’ boundaries, Pentagon spokespeople say they don’t have maps. Neither did the military confirm whether a map by the Bureau of Land Management of the land it transferred in New Mexico to the Army matches the new military zone in that state.

When the Monitor shared that map with Doña Ana County Sheriff Kim Stewart earlier this month, she said it was the first time she’d seen it. No Defense Department officials had contacted the border sheriff, whose county overlaps with the Army’s new turf, she says.

“We like help,” says Sheriff Stewart. “We just want organized help and everybody to know their roles.” Her office is tasked with investigating deaths in the county, including those of unauthorized immigrants. She wonders who is supposed to tend to deaths in military zones now.

The military says Customs and Border Protection (CBP), which includes the Border Patrol, leads coordination with local law enforcement.

El Paso Sector Border Patrol agents will operate in the new defense areas as they did before the zones were created, says Landon Hutchens, a CBP spokesperson. That includes referring all death investigations to the relevant state or local authorities.

Confusion around the existence and boundaries of the new zones has also reached the courtroom. The U.S. attorney in New Mexico reports charging 472 people so far with violating a security regulation tied to the New Mexico National Defense Area. The office noted the potential penalty of up to one year in prison, in addition to legal consequences for other immigration-related offenses.

Legal issues are arising around whether unauthorized immigrants were aware of their alleged trespassing. On May 14, a federal magistrate judge dismissed trespassing charges against 98 unauthorized immigrants for entering the New Mexico National Defense Area, reported The New York Times. The judge found the government had not demonstrated that the defendants knew they were entering a restricted military area.

Do people “know what they’re getting themselves into”?

There are locals, including law enforcement, who embrace the military’s expansion outright.

In New Mexico’s westernmost “boot heel,” Hidalgo County Sheriff William Chadborn says he hasn’t heard directly from the military about its expansion in his area. Still, he supports the soldiers’ presence – and hardening of the border generally – as a way to deter border-crossers from the dangerous trek.

“I really don’t believe that the people that are signing up for that walk know what they’re getting themselves into,” he says.

From her family’s pecan farm along the border in Clint, Texas, Jennifer Ivey also approves.

Given gaps in border fencing, “We’re never going to have enough men protecting our country, and that’s what the military is doing,” she says. During the Biden administration, she says, several farm workers quit due to incoming gunfire from the direction of Mexico. She says unauthorized immigrants have been found dead in irrigation canals on the farm.

While she welcomes soldiers on the property in the future, she says she’d like clarity on how to contact them, or the Border Patrol, to report unauthorized people on the farm.

Along the border in Sunland Park, New Mexico, Robert Ardovino says he’s long dealt with crossings by unauthorized immigrants near his restaurant and inn. He estimates spending hundreds of hours patching holes in fencing used by them to enter the United States.

Still, “I’m not interested in the military militarizing that border that, in my opinion, did not need militarizing,” says Mr. Ardovino. He’s also frustrated that he doesn’t yet know if the land where he routinely hikes now belongs to the Defense Department.

Others in the business community are dealing with outside perceptions. As president of The Border Industrial Association, Jerry Pacheco says he’s fielded questions about the troops from a foreign company he’s trying to recruit into the region.

“The optics are challenging,” he says at his office in Santa Teresa. Mr. Pacheco expects more questions, especially from foreign firms, “wondering why we look like the Gaza Strip.”

Pushing back

Environmentalists are opposing the militarization and border-wall construction, which they say fragment wildlife habitats.

The military takeover of land, which did not involve Congress, is a “dangerous precedent,” says Michelle Lute, executive director of Wildlife for All. “If left unchecked,” she says, “this could normalize the use of national security as a blanket justification for sidelining all kinds of environmental oversight and democratic land management.”

The Army is not directly responsible for protecting federally endangered species, says Sergeant 1st Class Redmond, the Defense spokesperson, but “will help protect these resources” through reducing unauthorized crossings that degrade the landscape.

Immigrant advocates have also pushed back. Fernando García, executive director of the Border Network for Human Rights, decries the Trump administration’s militarization of the border and further criminalization of immigrants.

The government is “distorting the deployment to appear to be aligned with the law and with the Constitution,” he says, as the national defense areas are “based on containing immigration.”

In downtown El Paso earlier this month, his group led a march calling for inclusion. Some participants carried American flags as children burst through a paper border wall. Marchers also carried an oversize copy of the Constitution.