The programmes of cultural institutions have taken a very queer turn of late. This year’s celebrations of Pride — the annual orgy of rainbow flags in which museums and galleries were once fully invested — have taken a bit of a nose-dive. Corporate sponsors pulled out of parties and marches whose organisers have become increasingly embroiled in internal disputes. The once celebratory “queering” of everyone and everything in the cultural record has given way to reflection. If only a couple of years ago, galleries celebrated difference, their queer programmes today focus on a rather different agenda: death.

London art institutions, in particular, have become fixated on the AIDS crisis. 2025 has seen a remarkable number of high-profile exhibitions that reflect on the relationship between sex, death, and the cultural artefacts that the two give rise to. Major shows that opened in close succession this Spring and Summer — of the activism of Gregg Bordowitz, the club life of Leigh Bowery, and the funerial anxiety of Hamad Butt — ascribe this intellectual project. Despite themselves, these shows unsettle contemporary art’s jubilant queer aesthetics.

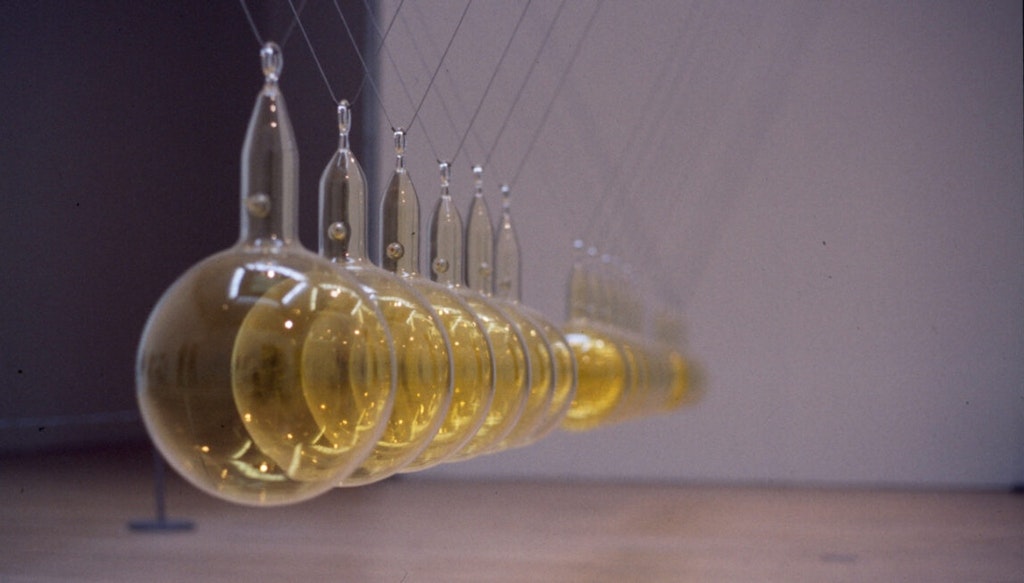

The late Hamad Butt’s Apprehensions, a sparse exhibition of sculpture and drawings at Whitechapel Gallery, is as far from “love is love” as it is sayable today. In a brief career before his AIDS-related death in 1994 at the age of merely thirty-two, Butt made a handful of installations that meditate on desire and peril. The show’s centrepiece is Familiars 3: Cradle, a giant reproduction of the business executive’s desk toy which served as a status symbol in the age of American Psycho. Butt’s version is made of glass and filled with chlorine.

It is difficult to follow Butt’s death drive is that Whitechapel installed his works behind thick barriers

Rather than induce the soothing click-clack sound of the pendulum, activating this Newton’s cradle would break the spheres and release the poisonous gas. Unfortunately, one understands this metaphor all too quickly, not least thanks to the graphic wall panels that outline the dangers. They do little, however, to address the compulsion to risky play that one might experience at seeing such an arrangement. Why, precisely, does the presence of danger amplify the desire for sensuality? Is this draw, dare one ask, as universal as today’s ideologues would have us believe?

A related work, Familiars 1: Substance Sublimation Unit — a tall, vertical ladder composed of steel rails and glass rungs — expands the confusion. The sculpture’s completion in 1992 coincided with the peak of Britain’s HIV crisis, and the ladder is a metaphorical means of escape. Its electrically heated and illuminated rungs — this time filled with vapourised Iodine — make this passage impossible.

One of the reasons that it is difficult to follow Butt’s death drive is that Whitechapel installed his works behind thick barriers so that however tempting their forms, no gallery visitor, whether clumsy or horny, could ever come near them. Butt’s written proposition that “the purity of each element is a measure of its poison”, familiar from the story of the early HIV treatment AZT later alleged to have caused more deaths than it prevented, is entirely absent from the work itself. Worse, and this is not something the exhibition’s curators would acknowledge, it throws into question the role of art and activism in creating a queer mythology. That the same question is unanswerable of today’s widespread use of PrEP, an HIV-prevention drug enabling unprotected sex, is taboo in queer circles.

Long before it became a catch-all term for all sorts of insufferable politics and behaviour, queerness was an attempt to separate homosexuality from sex and thus the horror of AIDS. That queers today might not have sex at all is, arguably, the legacy of a time when sexual activity was synonymous with decay. Butt’s work, as interpreted by the generation of curators who followed him and who fully embraced its desexed aesthetics, lacks the conviction to interrogate this proposition.

Across the river, the life and output of Butt’s contemporary Leigh Bowery lies reconstructed for the enjoyment of purple-haired 20-somethings by Tate Modern. The exhibition turns the birth of queer into a mindless celebration. In Tate’s telling, the club kid Bowery’s antics in the 1980s are why Britain had an independent cultural scene at all.

The Australian, whose resolution on moving to London was to “become established in the world of art, fashion or literature”, was, indeed, present and notable for his outrageous outfits at many of music’s, fashion’s, and art’s key events of the period. Artists like Stephen Willats, known for his earlier graphic treatment of Britain’s harsh social realities, paid homage to Bowery’s subcultural existence with works like the 1984 What is he trying to get at? Nick Knight photographed him, Cerith Wyn Evans and Charles Atlas filmed his performances, and Lucian Freud painted him.

Yet Bowery was not, in the strict sense of the word, an artist, and few of the ephemera associated with him are museum-worthy. The exhibition’s implication that Bowery set the tone for today’s sexual and aesthetic libertinism is an exaggeration that future art historians engaged in a project of “unqueering” the 1980s will need to correct. It’s not that Bowery’s behaviour didn’t shock (the show gets giggly about his infamous glitter-spray enema performance), nor that he didn’t pursue freedoms we deny ourselves today (the exhibition lacks any reference to the period Bowery spent wearing blackface in public). What his work did, not least to its own detriment, was enable many others to understand their hedonism as an art form.

Tate’s pile-up of silver knickers, club photographs, and TV clips, interspersed with the odd artwork, provides an alibi for those who outlived Bowery. A promotional film on the museum’s website reconstructs “Leigh’s Lounge” in which the likes of Les Child, Boy George, and Rachel Auburn, once Bowery’s friends, refuse to grow up as they reminisce. Despite failing to acknowledge finitude — Bowery passed the same year as Butt, at nearly the same age, and for similar reasons — this version of queerness disingenuously becomes its celebration.

Who survives death? “Romance difference expectations crude petroleum jelly”, read one of many lines of poetry by the American artist and AIDS activist Gregg Bordowitz, set in a Roman typeface on the walls of Camden Art Centre. Debris Fields is like a memorial: a collection of ideas that can no longer justify their circulation.

This abstract textual epitaph was poignant next to Portraits of People Living with HIV, a candid 1993 film depicting the perfectly ordinary lives of New York’s gay men, ordinary in the sense that they were not immune to suffering and horror. Today, this work looks like an infomercial trying to “destigmatise” the disease. This aim was, indeed, one of the strategies of activist groups like ACT UP, of which Bordowitz was a member, and the style of the film has not been without consequence to the aesthetics of social advocacy.

Bordowitz’s painterly practice, shown off in the exhibition on multiple wooden scaffolds that barely made up for its paucity, undoes what Bordowitz the poet invested in language and representation. The basis of these monotype works is a meditation on the tetragrammaton, the graphic form of four letters that together make up the unsayable name of God in the Torah. One could not help but wonder what, exactly, is still unsayable for the artist known as a consummate, if not sanctimonious, raconteur whose survival has depended on speaking up (the exhibition included a bizarre 70-minute video compilation of his sermons and stand-up routines).

This exhibition, like the Bowery hagiography and the posing of Butt as the artist of the death drive, felt indulgent. The latter shows might have been desperate attempts to historicise cultural moments that have become corrupted precisely because our culture has given queer histories so much attention lately. Bordowitz, on the other hand, seems to have been granted his opportunity in recognition of his sheer staying power, although it was unclear whether it was his long-term HIV diagnosis or his limited interest in aesthetics that was the exception.

Leigh Bowery! continues at Tate Modern until 31 August, while Apprehensions by Hamad Butt are on at Whitechapel Art Gallery until 7 September.

Pierre d’Alancaisez is currently editing Inversion, a collection of essays examining the relationship between homosexuality and culture, to be published in November.