The Holocaust survivor who inspired the bestselling novel The Librarian of Auschwitz has died aged 96.

Dita Kraus passed away at her home in the Israeli city of Netanya last Friday, surrounded by her beloved family.

Her story of resilience amidst the horrors of the Nazi death machine inspired and moved millions of readers.

After arriving at Auschwitz death camp in Nazi-occupied Poland aged just 14, Kraus ended up curating what she would go on to call the ‘smallest library in the world’.

Of those 12 or so books, only HG Wells’ 1922 work A Short History of the World – translated into Czech – would stick in Kraus’s memory.

But that and the other works which were found in the luggage of doomed arrivals nourished the souls of Kraus and other inmates amidst unimaginable horrors.

One such trauma was Kraus’s witnessing of starving women cooking human livers at Bergen-Belsen, where she was transferred in 1945.

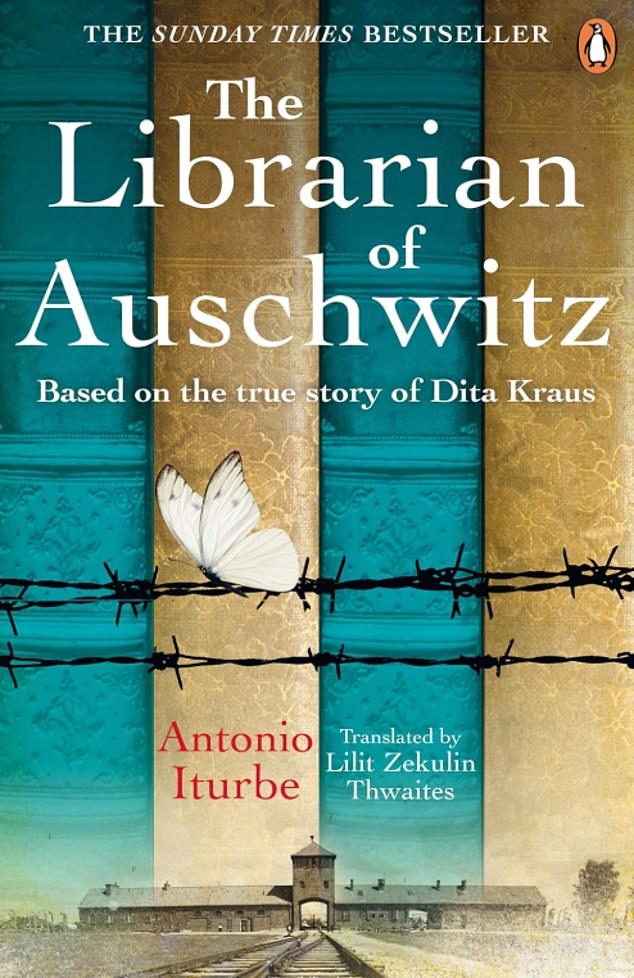

Her remarkable life story was re-told in the 2012 novel by Spanish writer Antonio Iturbe became a worldwide bestseller.

The Holocaust survivor who inspired the bestselling novel The Librarian of Auschwitz has died aged 96. Dita Kraus died at her home in the Israeli city of Netanya last Friday

Her story of resilience amidst the horrors of the Nazi death machine inspired millions

In 2020, Kraus released her own memoir, A Delayed Life: The True Story of the Librarian of Auschwitz.

Announcing her death in a moving post on Facebook, Kraus’s son Ron said his mother’s final act was to ask for a sip of water. She then passed away peacefully.

She was laid to rest on Monday.

The daughter of a law professor, Kraus was born Edith Polachová in Prague in 1929.

She would only learn of her Jewish heritage when Adolf Hitler’s Nazi forces occupied what was then Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

In 1942, Kraus and her family where deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto in the Czech town of Terezin.

There, they had to contend with immense overcrowding and little food.

In 1943, things got worse when the family were sent to Auschwitz, where they were put in the camp for Czech families.

Her remarkable life story was re-told in the 2012 novel by Spanish writer Antonio Iturbe became a worldwide bestseller

Within weeks of their arrival, Kraus’s father died.

Youth leader Fredy Hirsch managed to persuade the camp authorities to create a daycare centre for the children.

There, he did his best to continue some form of education for Kraus and others her age and younger.

Among the instructors who helped teach the youngsters was Otto Kraus, the survivor’s future husband.

Hirsch also put her in charge of looking after a handful of books that had been found in the luggage of arrivals.

Whilst Kraus would only remember Wells’ work, other survivors could recall an atlas, and a work by the psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud, among others.

Kraus explained in her memoir: My role was to watch over the 12 or so books that constituted the library.

‘On the ramp, thousands of Jews arrived daily. They were led away, but their luggage remained behind.

In the early 2000s, during a visit to the Imperial War Museum, Kraus spotted herself in footage of Belsen’s liberation. She was seen sharing a cigarette with a British soldier

‘A number of lucky prisoners had the task of sorting their content.’

She added: ‘If the Germans had found me with those books they might have killed me.

‘The fact that I was able to sit indoors and not do strenuous work in the cold gave me a chance to save my strength and in fact enabled me to be chosen for life.’

But Kraus’s role as a young librarian would not last long. After six months at Auschwitz, Kraus and her mother were among around 1,000 women and girls who were sent first to a work camp in Hamburg.

During the selection process at Auschwitz, she narrowly escaped death by lying about her age and pretending she was 16.

If she had told her actual age, which was 14, Dita would have likely stayed behind and been killed in the gas chamber with the other children who remained in 1944.

Then, in 1945, Kraus was sent to Bergen-Belsen in northern Germany.

‘What happened next cannot be described; human words fail to convey such hell. Yet I will try to speak about it because I must,’ Kraus wrote.

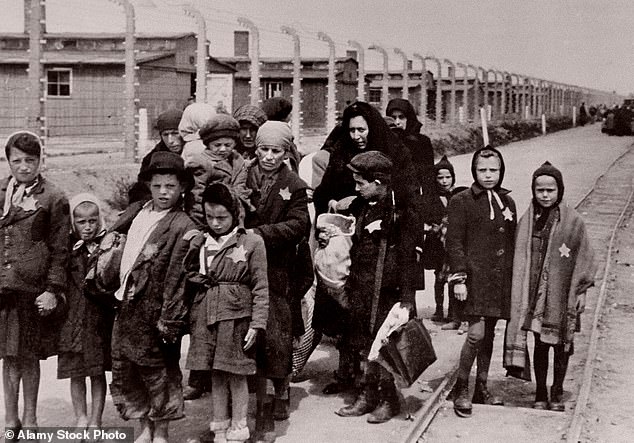

Jewish children wearing Nazi-designated yellow stars are pictured arriving in Auschwitz-Birkenau

By the time the camp was liberated by British troops in April 1945, tens of thousands of prisoners had died of starvation and disease.

Thousands more were found perilously close to death. BBC broadcaster Richard Dimbleby revealed the horrors to the British people in a radio report that would go down in history.

Kraus recalled how, after the water supply broke down before liberation, prisoners were left attempting to drink water from a leaking pipe in the camp’s latrine.

‘The dead lay everywhere,’ she said. ‘The limbs were just bones, fleshless, covered in skin, the knees and elbows like knots of ropes sticking out of the heap at incongruous angles.

‘The weakened inmates had no strength to walk to the latrine and just relieved themselves wherever they sat. They also died there.

‘In a short time there was no way to get around without stepping over the dead.’

By this time, Kraus had become desensitised to the horror. ‘I felt nothing at all… I existed on the biological level only, devoid of any humanity,’ Kraus wrote.

Describing the sight of gypsy women eating human livers, she added: ‘There was no revulsion or horror, although the implication of what I had seen did register in my brain: I had witnessed cannibalism.’

Kraus boldly admitted that she too may have joined them had she been asked. ‘Today I hope I would have refused, but I am not certain.’

When liberation came, Kraus was on the brink of death. After recovering, she worked as an interpreter, helping British soldiers interrogate SS guards.

Kraus’s mother tragically died weeks after liberation. Then only 17, her daughter now had to make her way without both her parents.

She and Otto struck up a romance and, after marrying, had first son Shimon.

They initially settled in Prague but then had to leave for Israel after the Communist coup in Czechoslovakia in 1948.

As well as their sons, Kraus and her husband also had daughter Michaela, who tragically died aged 20 after falling ill with a liver condition.

In the early 2000s, during a visit to the Imperial War Museum, Kraus spotted herself in footage of Belsen’s liberation. She was seen sharing a cigarette with a British soldier.

In seeing herself, Kraus was able to confirm that her memories were real, ‘tangible’ evidence of the horrors of the Holocaust, and not a distorted memory.