Although talk of a “Quiet Revival” of Christianity in the UK is probably over-egged, there is a clearly an element of truth to it: congregations in some churches do appear to be picking up, especially among the young. What is absolutely clear is that the revival of Christianity among young people is overwhelmingly occurring among those disillusioned with the sterility and emptiness of secular modernity.

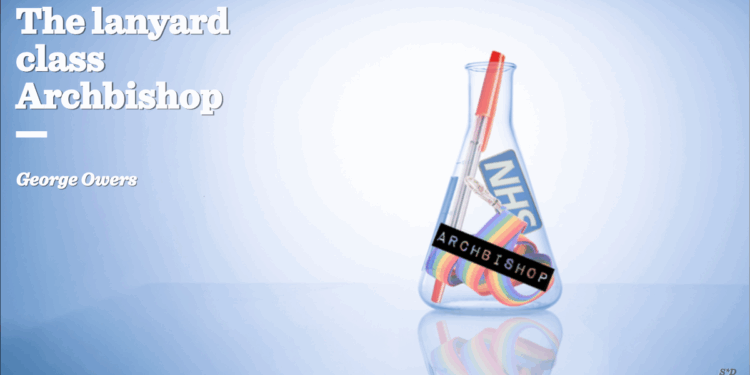

What such people are looking for, as James Marriott showed comprehensively in a recent Times piece, is “full-fat faith”, that is, forms of Christianity that unapologetically adhere to the traditional practices and doctrine of their respective denominations, or perhaps are the most sharply counter-cultural and unapologetic in their supernaturalism and rejection of liberal pieties. Such pieties are usually theological but often also political, in the sense of constituting the semi-secularised milk-and-water forms of Christianity which present themselves in terms almost indistinguishable from the beliefs of, say, Oxfam or the average Guardian leader: a “religion” of lanyard class talking points with occasional mentions of God. Unsurprisingly, therefore, the revival is happening most obviously among trad Roman Catholics, assertive evangelical or charismatic sects, and similar.

In this context, it appeared to be a great gift of providence that Justin Welby stepped down as Archbishop of Canterbury just as this revival gathered steam and the cultural moment was changing. New Atheism is cringe; everyone’s read Dominion by Tom Holland; many can see that what has come after Christian hegemony is far worse. People are looking for something different. As Nick Cave said recently, the most countercultural thing you can do is go to church. The time was ripe for a new Archbishop of Canterbury well-placed to exploit this new atmosphere: a theological heavyweight and spiritual big-hitter who could speak a more traditional, uncompromising language, tone down the Church of England’s invariably progressive mood music, and challenge the church’s creeping culture of bland managerialism. No one was expecting a Prayer Book purist who knows the Thirty-Nine Articles by heart, but it wasn’t absurd to hope for a small move in the right direction.

Even I was a bit taken aback at the sheer perversity of this choice

If I were to try to imagine a candidate for the new Archbishop of Canterbury who is the furthest away from this, the worst and least suitable replacement for Welby possible, I would probably pick someone along the following lines. They’d be a former state bureaucrat who made an entire career out of the sort of bland HR department-inspired managerialism that is destroying the church, probably a senior civil servant in (say) the NHS. They’d be on record as having every tick-box lazy progressive political and theological opinion imaginable. They would, of course, have lived and worked in London for most of their life and be a thoroughgoing metropolitan. They would have no record of any serious theological or scholarly work, but be thoroughly intellectually mediocre.

Whoops, I just described the person announced this morning as the new Archbishop of Canterbury, Sarah Mullally. The Church of England making an appalling decision is too common to be surprising, but even I was a bit taken aback at the sheer perversity of this choice. She is the pure distilled essence of the hectoring lanyard class, a bureaucrat, a proceduralist and a progressive down to her fingertips. Her entire professional career was spent in the NHS, latterly as Chief Nursing Officer and “Director of Patient Experience”; she is on the record as being “pro-choice”, pro-gay marriage, on board with the usual check-box list of LGBTQIA+ orthodoxy; she has lived in London for most of her life. She will occupy an Archiepiscopal throne once occupied by theologians of the calibre of Anselm, Cranmer, Michael Ramsey and Rowan Williams: her sole contributions to the intellectual life of the church are a couple of those paper-thin (in every sense) “Advent/Lent reflection” books, the authorship of which appear to be compulsory now among senior bishops, and the readership of which is close to non-existent.

Although my first thought was that she is just pure Welbyism redux, right down to the less-than-pure record on clergy discipline and safeguarding, my second thought was worse.

One might remember that Paula Vennells, later disgraced for her culpability in the Horizon postmaster scandal, almost became a bishop. It was only sheer luck that saved her from being catapulted from a senior position in the quasi-governmental senior management class onto the episcopal bench: indeed, she was one of the rivals for the job of Bishop of London when Mullally was appointed, backed by Welby. There, but for the grace of God and some investigative journalists, goes the person who the establishment might now be celebrating as the first female Archbishop of Canterbury instead of Mullally (which I suppose is some sort of mercy).

Now, there is no reason to think that Mullally was responsible for any comparable scandal when a senior bureaucrat in the NHS, but in many other respects Mullally and Vennels are strikingly similar figures: both pursued careers within the nexus of the bureaucratic-management state and its corporate appendages and have near-identical views and backgrounds. They are both mediocre non-entities promoted above their abilities, partly, no doubt, to burnish the feminist credentials of those who appointed them, partly because their anaemic liberal views challenged no-one and they could be relied on to keep the procedural wheels of their respective institutions rolling. They both saw a second career in the Church as a natural extension of their first careers as managers within the therapeutic-technocratic state.

As such, it seems highly probable that Mullally has inherited much the same sort of mindset as Vennels, i.e. the classic mental toolkit of the modern day British state managerialist. For these people, there are only a few overriding objectives. Firstly, they promote the interests of the management class, specifically by increasing the authority and number of bureaucrats — sensible “people like us”, managers who can be trusted to stamp out any outbreaks of people actually doing their job properly. Secondly, to them “inclusion”, defined in purely secular DEI-style terms, is sacred. Finally, their overarching priority is reputation management and “comms”, and these things overrule everything else. The actual purpose of the institution — saving souls, ministering to the nation, spreading the gospel etc — will always, in people of this background and class and politics, come second, and if pursuit of their main goals is compromised by such inconvenient things as “being the Church of Jesus Christ”, then it’s Christ who loses out.

The ministry of the Church of England to the nation has already been severely imperilled by the widespread impression that its leadership caters only to a tiny segment of progressive urban Christians of liberal theology, that it is the “Lib Dems at Prayer”. This tiny group — mainly found within the Church’s leadership class — is happy to speak out on public affairs only when its controversial views coincide with the secular-liberal consensus of the BBC executives, politicians and journalists. As they are essentially part of that consensus, that is almost always. (I will make one concession here, which is that despite scandalous views on abortion, Mullally has been sound so far on assisted suicide — that is about all that can be said in her favour). Seating the human embodiment of the lanyard class on the Chair of St Augustine will only compound the existing negative impression that huge swathes of the country already have of the Church and make it seem off-limits to the vast majority of the non-progressive masses.

This is, in a sense, apt. Most of the Church of England is already run by people like Mullally, and installing one of their own at the top is only cutting out the middleman. More broadly, it is very much of a piece with the general drift of our national institutions: the Church is becoming just another legacy institution gutted of its essential purpose and made into an instrument of an incompetent, distant, unpopular technocratic liberal state. Her appointment is, in a sense, the logical conclusion of this process, of the victory of Rainbow Flag Erastianism, the view that the Church is basically the spiritual equivalent of the NHS and subject to all of the progressive ideological orthodoxies that constitute our real — and politically determined — state religion.

And so it seems almost certain that the Church of England will miserably fail to take advantage of the enormous opportunity that the “Quiet Revival” affords. Many coming to Christianity from secular backgrounds are running away from the precisely the vacuous milquetoast progressivism that Mullally is such an obvious representative of, and are hardly going to be attracted by her as Archbishop. No doubt some heroic parishes and priests within the Church of England — the ones that embrace “full-fat Christianity” rather than her sterile liberalism — will find ways to flourish, but as a broad national church, in vast swathes of the country, we will continue to die, eaten alive by the twin cancers of metastasizing managerialism and liberal indifferentism.

I sincerely hope that I am mistaken. I don’t know her personally, and however sceptical I am of her I will pray for her ministry. Nonetheless, I think it’s vain to expect someone whose origins lie deep within the belly of the beast to be inclined to help slay it. Perhaps her pastoral skills will be her saving grace, as some claim. I remember people saying the same of Welby, and I wonder what, say, those who know and loved Fr Alan Griffin, driven to suicide by vague and unsubstantiated allegations of sexual abuse in her diocese, would say about that. I suspect that her pastoral skills are similar to the people skills possessed by HR managers who hand over P45s in an inappropriately matey and upbeat manner, as if one should be grateful for being sacked. They’re not the pastoral skills that many sheep are terribly grateful for.

Perhaps Mullally will even have the political antennae to tone down her worst instincts and simply preside over the same failed Welbyite approach with fewer obvious gaffes and without grinding our faces into the dust too harshly. The only consolation is that our extinction as a Church is not — if the faithful laity are prepared to assert themselves against the cowardly leadership class — inevitable. We are still God’s church and the gates of hell will not prevail against us, however much we might dread the coming years. Let us take comfort in that and pray for deliverance.