The inauguration of Ireland’s new far-left President, Catherine Connolly, this week firmly places the nation at odds with much of the western English-speaking world, where refusal by the political classes to listen to the growing discontent among its people has led to the Overton window being exponentially shunted rightward.

Connolly, despite being an independent candidate for the Presidency, secured rigorous backing from Sinn Féin, a party which, in the Irish Republic, sits firmly to the left of the two more establishment parties, Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil; their leader Mary Lou McDonald appeared jubilant at the result of the election, saying “the next job is to get Fine Gael and Fianna Fáil out of Government”.

In Northern Ireland, Sinn Féin are the largest party, being responsible for the office of First Minister through the anomalous auspices of Michelle O’Neill, who doesn’t recognise the country’s existence. O’Neill shared her “great privilege” in attending, through her role as First Minister, the inauguration on Tuesday of “our new President”. The choice of wording is revealing; Connolly is not a politician with any role, ceremoniously or otherwise, in Northern Ireland, which, being a constituent part of the United Kingdom, does not have a president, but a Prime Minister and King. In her inauguration speech, likely to the intense dismay of the First Minister, Connolly referred to her as “Michelle Smith”, seemingly confusing her with the former Olympic gold-medal winning swimmer. One imagines this error has already landed an aide in hot water.

The phrasing of “our new President” betrays the true objective of this renewed cross-border alliance: that the fight for a unified Irish state will be at the forefront of objectives for the unified nationalist front. As Owen Polley wrote recently in these pages, before the outcome of the election was set in stone, “Every political campaign in the Republic, even one for this ceremonial position, seems now to require candidates to set out their annexationist plans for Northern Ireland”.

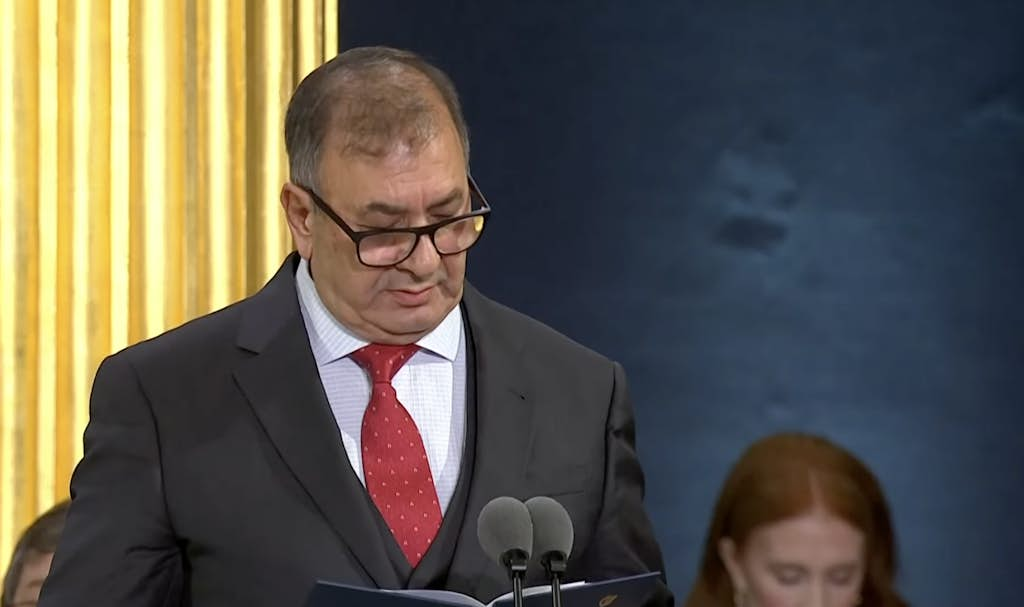

For Connolly, this desire for a United Ireland extends beyond remarks aimed at appeasing radical voters. A significant portion of her inauguration speech was devoted to criticising British rule in Northern Ireland, peddling the common lie of the “catastrophic man-made famine” in Ireland being the wilful fault of Britain and colonialism. She referenced Article 3 of the Irish Constitution, which reiterates the aspiration of Irish nationalists for one united Ireland. Connolly continued by emphasising that the Irish language would become the working language of the Presidential office.

There was also a mention of the act of showing “resistance” against “forced immigration”, not referring to the mass influx of illegal immigrants transplanted into Ireland at the hands of the state, but rather that of British people several centuries ago, whose existence in Ireland has become as much a part of the fabric of the island as the shamrock or the colour green. Even the style and uniform of the Army No. 1 Band welcoming the new President with a jubilant musical ensemble was formed based on the precedent set by the British Army Corps of Army Music.

For people like Connolly, the people whose ancestors ended up in Ireland as a result of a lack of peasant proprietorship of land in Scotland and northern England several hundred years ago will never truly be of equal footing in this new Ireland. But those who arrive as stowaways in the back of a lorry like a crate of illegal fireworks will be welcomed with open arms.

This could hardly have been exemplified more clearly than in the second-place contender for President, the Fine Gael candidate Heather Humphreys. Humphreys, an Ulster Protestant from an Orange Order parade-attending farming family, disclosed that she and her family were subjected to “awful sectarian abuse” throughout the Presidential campaign.

While Humphreys is certainly no Ulster Unionist, she would have been well placed to appeal to this segment of the Irish population — at least, more than the alternative. Her grandfather signed the Ulster Covenant, opposing Home Rule in Ireland, while during her 13-year stint as a member of the Irish Parliament she was the only Presbyterian in either house; as the largest Protestant denomination in Northern Ireland, this, surely, would have counted for something.

Humphreys won less than 30 per cent of the vote. While certainly not having views that would appeal to the groundswell of vocal anti-immigration sentiment in Ireland, she took a firmer stance on the issue than Connolly, conceding that those who have no valid claim to asylum in Ireland should be deported. It is dismaying when such a boring, obvious platitude seems radical when compared to the alternative. Instead, Ireland has ended up with a new President who invites a Muslim faith leader on stage during her inauguration to recite an Arabic blessing. Certainly, to her supporters this will be evidence of her claim that she will represent “all voices” in Ireland; to her detractors, this will be the first of many signs that she will not listen to theirs.

Catherine Connolly is not the President of my country, but she would like to be. It would be an unlikely event. Those candidates who argued in favour of more conservative viewpoints, such as Maria Steen who gained mass popular support by having views on abortion and euthanasia that should be considered normal, could not even get their names on the ballot paper due to a prohibitive selection process. Far be it from me to want to interfere in a foreign election, but it would behove Ireland to at least attempt to represent the significant portion of its country who would lean right. Ireland used to be a Catholic country, after all.