The handwritten letter from a dying father to his four-year-old son could not have been more heartfelt.

‘My darling Edward,’ it read. ‘Just a little letter to you but not much… because you can’t read yet, can you? Are you going to be a good boy for Mummy always? I hope you always do what Mummy tells you.

‘Be clever and good and happy and a credit to Daddy always. Lots of kisses and many more, Mummy will give them to you from me.’

Barely eight weeks later, John Davey, 38, the solicitor father of three boys under the age of 10, died of Hodgkin disease and his letter was handed over to ‘darling Edward’ – today better known as Sir Ed Davey, the leader of the resurgent Liberal Democrats – when he had learned to read.

There is an almost unbearable postscript to the letter. Five years after it was written, Davey’s mother Nina was diagnosed with breast cancer. She had two mastectomies but six years later she died, aged 44, after the cancer spread to her bones.

Davey, the boy who had often acted as her carer, was holding her hand at her hospital bedside in his school uniform when she passed away in 1981.

‘Mum devoted herself to us after Dad had gone,’ he says. ‘She found the cancer was back and went into her bones when I was 12. She started spending money. She wanted us to be happy. There were holidays. We had a colour television with a remote control. She wanted to ensure we had good memories. She was amazing.’

Close to tears as he spoke, Davey says she looked at peace when she finally slipped away. ‘One of the most horrible things about bone cancer is the awful pain. The bones are literally crumbling.’

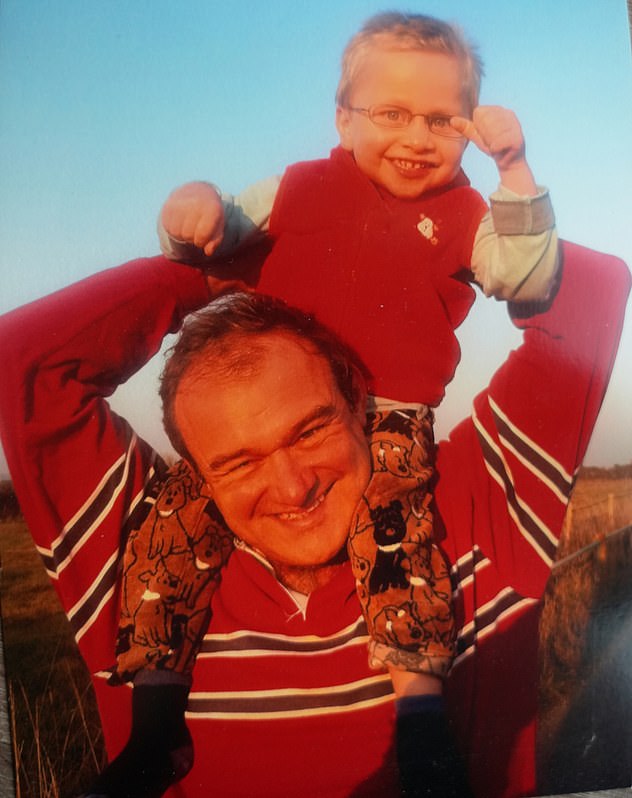

Ed Davey with his son John, who has a rare and undiagnosed neurological condition. He can’t walk unaided and for years he was non-verbal, uttering the words ‘Mummy’ and ‘Daddy’ for the first time only when he was nine

Unusually frank for a politician, Davey reveals they would not be able to afford John’s care, which runs to thousands of pounds a year, without the financial support of a tight-knit circle of family and friends

His parents’ death and the story of how the 15-year-old orphan was brought up with his two older brothers – Charles, 20 at the time, and Henry, 18 – by his maternal grandparents are recounted in Davey’s new book, Why I Care: And Why Care Matters.

It is a deeply personal account of caring not just for his mother but for his son John, 17, named after his late father.

John has a rare and undiagnosed neurological condition. As a baby he could not sit up – his body would flop over. To this day, John can’t walk unaided. For years he was non-verbal, uttering the words ‘Mummy’ and ‘Daddy’ for the first time only when he was nine.

Davey, 59, speaking to me on a sunny day in an open-air cafe in Westminster’s St James’s Park, says: ‘We never underestimate him. He has a sense of humour and laughs when you didn’t think he would understand.’

John attended a series of special schools but none worked out and the Daveys reluctantly concluded that they should educate him at home.

Davey’s wife Emily, who he married in 2005 having met her at a Lib Dem housing group meeting, sits with John for hours each day, reading him stories word by word. As a result of this painstaking care, he can now make limited conversation.

‘Some conversations make more sense than others,’ says Davey. ‘But his effort to reply is huge. When I hear the words in the morning from his bedroom: ‘Daddy, get up’, it’s music to me. They are the most important words of my day. I get him up, sitting at the side of his bed, because he can’t do it by himself.

‘He likes to play his wooden acoustic guitar with his mother and father on either side of him. He has a toy parrot which he talks to, which speaks back to him, to encourage him to speak. I take his nappy off, take him to the shower, wash, dry him and clean his teeth.’

The Daveys on their wedding day. Both would die young – John aged 38 of Hodgkin disease and Nina of breast cancer when she was 44, leaving their sons orphans

The 30-minute routine is sacred to Davey. ‘He is a happy, smiley boy. We have a wonderful relationship. Caring can be tough and challenging. But I would hate not to have my John. We have fun and happiness together.

My biggest fear is when we are not here – who is going to look after him?’ John’s development is being helped by regular trips to the Peto Institute in Hungary, which specialises in neurological disorders in children.

‘We were told we should put John in a wheelchair… wrap him in cotton wool,’ says Davey. ‘But the Peto said no. We have to push him. At the Peto they work John hard with all sorts of different exercises. Emily takes notes so we can repeat the exercises when we come back. He is not always willing but he does it in the end!’

Next week Emily, who was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 2020 and now walks slowly with the aid of a stick, will go to the Peto with John and their 12-year-old daughter Ellie. Davey will join them the week after.

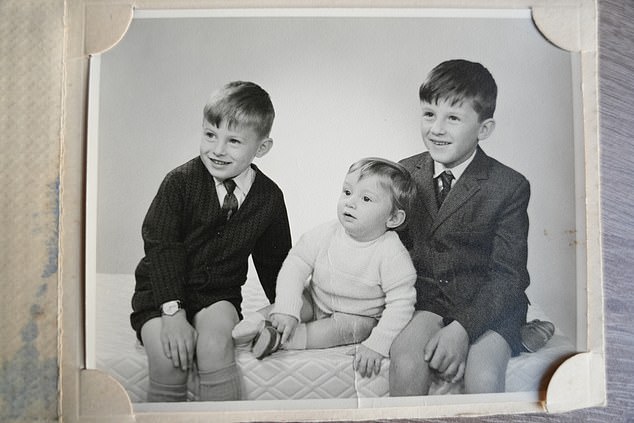

Pictured in 1966, Ed with his older brothers, Charles (left) and Henry

The cost of a live-in carer and regular trips to Hungary would stretch anyone’s finances and the Daveys, who rely on his MP’s salary of £94,000, while Emily earns £21,000 a year as a Kingston district councillor responsible for housing, are by no means wealthy.

Unusually frank for a politician, Davey reveals they would not be able to afford John’s care, which runs to thousands of pounds a year, without the financial support of a tight-knit circle of family and friends.

‘We have friends and family who help. The trips to the Peto are the biggest costs, especially the flights and accommodation. I am so grateful. We just could not afford to do it without that financial support.’

Given his family background, Davey’s views on assisted dying are worth listening to. The Commons this week debated the latest stage of Labour MP Kim Leadbeater’s assisted dying Bill, while in Scotland a separate Bill on the same issue passed its first vote in the Holyrood parliament.

The death of his parents has made Davey think long and hard about palliative care. I ask him if his mother, who suffered so much in her final years and had experimented with natural remedies after radiotherapy and chemotherapy failed, would have supported the Bill.

‘I have always been opposed to assisted dying and Mum would have been opposed to it,’ he says. ‘She wanted to be with us for as long as she could. She wanted to fight for her sons for as long as she could, even though she was in agonising pain.’ Davey is also concerned about how any new legislation could put pressure on terminally ill older people.

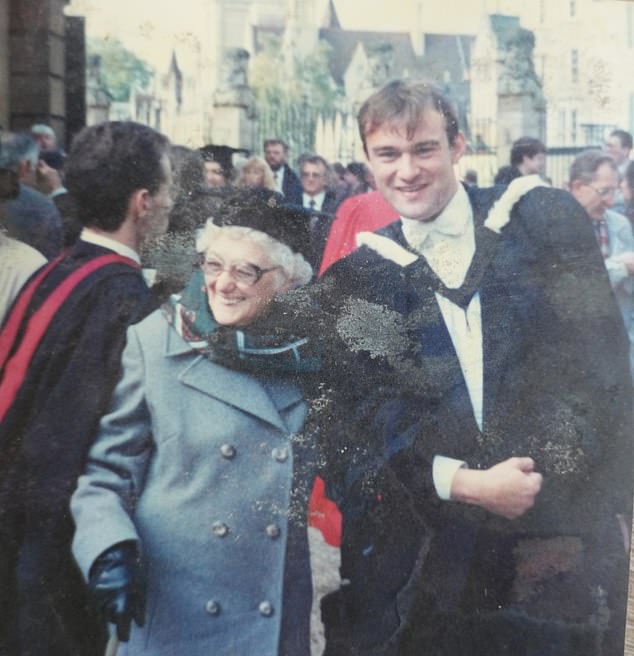

Davey at his graduation with his proud maternal grandmother, Nanna. He attended Jesus College, Oxford, where he was awarded a first class BA degree in philosophy, politics and economics in 1988

‘I fear they will opt for assisted dying even if they don’t really want it but are worrying about becoming a burden on their loved ones. Even though their loved ones might be caring for the sick relative, they still may think they should choose to die.’

Davey’s strong Christian faith is another factor in his thinking. A practising Anglican, he goes to church every Sunday. ‘My wife reads the Bible in bed,’ he tells me.

He is horrified by one particular consequence of the Labour government’s decision to hike employers’ national insurance, which has resulted in some hospices being forced to close beds and cut staff. ‘It is beyond shocking,’ he says.

In the book he also argues there is a solution to the carers shortage, estimated to be running at 135,000. ‘We have to pay them £2 an hour more than the minimum wage [currently £12.21 for workers aged over 21]. If we do that we will find a lot more people living here will do the jobs,’ he says.

After the week in which the Government said it would stop foreign workers taking carers’ roles, Davey insists the visa system is being abused. ‘Over the last four or five years under the Tories, 450,000 health and care visas were issued. If all those people worked in health and care, we’d not have a problem,’ he says.

‘If I was Home Secretary I would say we have to pay people here more to do the job. I would also ask: where are all the people who came to our country on health and care visas? What are they doing?’

Davey led the Lib Dems to their best general election performance last year with a record 72 MPs and in this month’s local elections the Lib Dems came second ahead of Labour and the Tories. This means his party’s new authorities will have to address some thorny issues, not least the Supreme Court ruling that a woman is defined in law by biological sex.

Davey, who was ridiculed when he said in 2023 that a woman could ‘clearly’ have a penis, was unequivocal when asked if he will accept the judgment: ‘Of course. I believe in the rule of law. We need a debate in Parliament to see how to give force to it.’

Davey, who was born in Mansfield, Nottinghamshire, on Christmas Day 1965, entered Parliament as the member for Surbiton at his first attempt in 1997 after a stint as a management consultant.

Between 2010 and 2012 he was Post Office Minister in David Cameron and Nick Clegg’s coalition government. His tenure coincided with growing realisation that hundreds of sub-postmasters had been mistakenly convicted of fraud due to the catastrophic failure of the Post Office’s Horizon accounting software.

The issue was front of mind when we talked because Mr Bates vs The Post Office, the dramatisation of the IT scandal, won best drama series at the Baftas.

Davey did not emerge well from the affair as he initially refused to see the former sub-postmaster who was leading the campaign against the Post Office, the now knighted Alan Bates.

‘I was lied to,’ he insists hotly. ‘I think my officials were lied to by the Post Office. There have to be prosecutions. I think officials could have done more but the real rotten apples are in the Post Office and the Fujitsu company.’

What of his decision to take a consultancy role with Herbert Smith Freehills, the law firm employed by the Post Office in 2019 to try to crush the likes of Sir Alan Bates? (A position which earned him a whopping £275,000 between 2015 and 2022.) Davey tells me he had no inkling that the law firm had been hired by the Post Office as he was nothing to do with its litigation side.

On the face of it, this is a surprising claim as his brother Henry, to whom he was very close, had been a corporate partner at HSF for approaching 20 years when Davey started working for the law firm.

During last year’s general election campaign, Davey engaged in a series of increasingly cringeworthy stage-managed photo opportunities, including juming off a paddle board on Lake Windermere while dressed in an overtight wetsuit

Since those days, Davey has reinvented himself as the court jester of British politics. During last year’s general election campaign, he engaged in a series of increasingly cringeworthy stage-managed photo opportunities.

Dressed in an overtight wetsuit, he jumped off a paddle board on Lake Windermere. Then there was a bungee jump from a crane. And perhaps most frivolous of all, a career down a water slide in an inflatable ring.

Why? ‘Boris and Trump got attention by doing fun things,’ he says. ‘I don’t model myself on them but if they are allowed to do it, why aren’t I? I spoke more about Lib Dem policy than in any other election because cameras turned up because I was falling off paddle boards. We had our best result in 100 years.’

Not everyone was impressed. Last month, former Tory Cabinet Minister Rory Stewart said he would consider voting Lib Dem but was deterred by Davey’s ‘gimmicks’. But no one can deny that, in electoral terms, Davey is the Lib Dems’ most successful leader of the modern era.

Likeable, hardworking, with an easygoing charm, Davey poses a serious threat to the Tories’ ‘wet’ brigade. Under him, the Lib Dems unseated four Cabinet ministers at the last election and captured three constituencies once represented by David Cameron, Theresa May and Boris Johnson.

Could he become Prime Minster? ‘I am not getting ahead of myself. But it will be an interesting journey and we might just surprise people,’ he says.