The death of the novelist David Lodge at the beginning of this year appeared to denote the end of a sub-genre that Lodge, amongst others, had been responsible for popularising, namely the campus novel. Beginning with Kingsley Amis’s Lucky Jim and Mary McCarthy’s The Groves of Academe in the Fifties, there was for decades a thriving literary market in well-written, often humorous novels that combined the bildungsroman tradition of young men and women groping their way into adulthood with the social and sexual exploits of the academics responsible for guiding their path into maturity. At their best, these books were comic masterpieces, but because of changing times and attitudes, they have largely been rendered redundant, replaced by the glummer and less convivial likes of Sally Rooney’s Normal People.

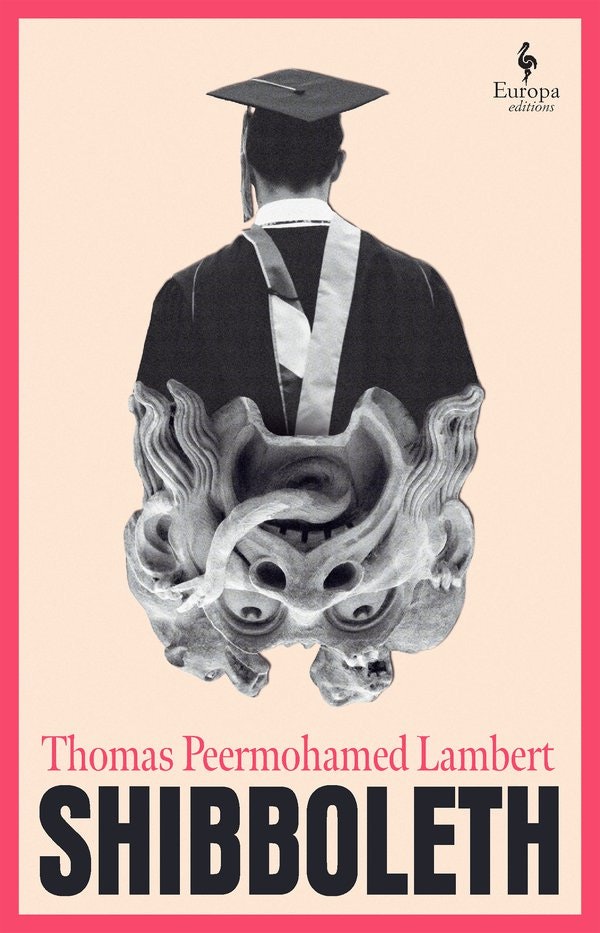

It is nothing less than a blessing, then, that the splendidly named Thomas Peermohamed Lambert’s debut novel is nothing less than a full-blooded, hilariously funny return to a tradition that I had believed deceased. Shibboleth has already been greeted with an unusual degree of admiration and acclaim for a first book, and its author has been interviewed in GQ for an article exploring the gender gap in fiction. However, the pleasures of this fine novel are far from tokenistic: somewhat ironically, given that its narrative revolves around the way in which contemporary university education has become mired in the most blinkered and repressive forms of tokenism, and that only the strongest-willed can resist the siren call of “fitting in”.

Lambert’s protagonist, in an unnamed college that boasts “Oxford’s least remarkable quad”, is the nondescript Edward, a state school boy who is diffidently studying English Literature and observing the anthropological spectacle of the various tribes and sub-tribes that surround him with an outsider’s curiosity. His best friend and boon companion is the charismatic, Falstaffian Youssef, a large, generous man whose professed dedication to all things Islam is undermined by his rapacious love for the pleasures of the flesh; not only has Youssef conceived an undying ardour for the ever-available Lolly Bunton, a girl “who catered to mass tastes — the football team, the rugby team, the water polo team and other assorted wretched of the earth” — but, as Edward observes, “you’re the least devout Muslim I have ever met. You have a whisky decanter by your bed. You own those shares in that ibérico pig farm.”

If Shibboleth merely concerned itself with the odd-couple relationship between these two, it would still be highly entertaining. Yet Lambert’s stroke of authentic literary genius — and a provocation of jaw-dropping brilliance — is to posit the idea that, because Edward’s grandfather is a Muslim from Zanzibar, he is himself considered both exotic and “necessary” by the ludicrously blinkered gatekeepers who make up the student body. Chief amongst these are the two frenemies who come to dominate Edward’s life in college: the splendidly monikered Angelica Mountbatten-Jones, a wealthy poverty tourist who derives giddy pleasure from bedding a real, live Muslim, and the terrifying Liberty Vanderbilt-Jackson, a privileged African-American whose fearsome commitment to social justice of all kinds is only mirrored by her ability to detect a fraud. This is something that Edward, under the boisterous tutelage of Youssef, finds himself becoming, as he attempts to embrace a hitherto non-existent Muslim identity, with his knowledge of his homeland largely derived from his dog-eared 1982 copy of The Wayfarer’s Zanzibar: Colour Edition.

Had this been put out as a 200-odd page novella, I suspect I would now be saluting an instant classic

Lambert is clearly indebted to a range of authors, from Lodge and Percival Everett to Amis pére et fils, and he proves himself just as capable as any of them at constructing a fine comic set-piece. The stand-out scene is when a reluctant Edward is dragooned by Angelica into attending a dismal and challenging literary evening in which students self-consciously read out their work (sample titles include a thirty-nine canto work about the Russian revolution, entitled “Love Beneath The Tractor”) and, by the time that the unfortunate protagonist is called upon to recite a traditional Zanzibari proverb that he has to improvise on the spot, it is likely that most readers will be gasping helplessly for laughter. Lambert has an Amisian knack for character names — we meet, in passing, Professor Larry Pfister and Hepzibah Coulson-von-Ribbentrop — and the people that he creates to match those names are indelible comic caricatures.

Yet if Lambert was simply a purveyor of superbly written jokes, Shibboleth would be an amusing but ephemeral distraction. Instead, this brings the campus novel into the 21st century with assured and at times angry conviction. Everything from the “Rhodes Must Fall” brouhaha to the current situation in the Middle East is referred to, and as Edward finds that his romantic involvement with the privileged, blinkered Angelica comes at the price of his preferred attachment to Rachel, his German-Jewish tutorial partner, he must also come to terms with his own racial and ethnic identity.

This allows for more excellent jokes than I have space to mention in this review — “How close to your neck of the woods is Nigeria?” — but also a thoughtful and genuinely provocative examination of contemporary mores, as best expressed through the novel’s true antagonist, Liberty: a self-proclaimed arbiter of what is and isn’t acceptable, who has been a bully since she was a child and has merely parlayed this aggression into a wider context, before she will seek to take over the world by using the privileges conferred upon her by her ethnicity, gender and background.

For its first two hundred pages or so, I was reading Shibboleth with jaw agape and sides in near-constant danger of splitting. A particularly successful running joke — the equivalent of Jim Dixon’s “faces”, if you will — comes in the form of the all too believable academic journals and books that Edward is forced to read for his course, including Anus Mirabilis: The Spirit of Freud in the Letters of San Juan de la Cruz and The Quality of Mercy is Not Stained: Shylock and the Poetics of Bodily Drainage. It was all I could do not to Google some of the titles to see how outrageous the exaggeration was.

Lambert hits all his satiric targets with gleeful gusto, and I often wondered how on earth a book like this had been published in this censorious, timid environment. The GQ interview alluded to how “while shopping the book around to publishers, fairly direct inquiries were made in some quarters about whether he had the ethnic background to justify it” — Lambert himself has a Zanzibari Muslim grandfather — and while the independent publisher Europa Editions has an estimable list, it says a great deal about the cowardice of larger establishments that this is not coming out from their better-funded imprints.

Yet, annoyingly, the book is not the perfectly polished masterpiece I had initially hoped it might be. It’s overstretched at 356 pages, and as it wears on, the dialogues and debates between characters begin to feel schematic, rather than provocative. There is a Palestinian student named Saïd who is introduced as a romantic rival for Edward, and he is more of a narrative device than a character. Meanwhile, a climatic antisemitic incident at a thinly disguised Oxford Union, while all too plausible, feels like a deus ex machina shoehorned in to underline the novel’s more serious points. Lambert keeps the laughs coming right up until the end, but when I finished reading, I wasn’t entirely sure what I was supposed to feel about Edward, whose dubious attractiveness to various women is never quite explained. He remains a weak-willed blank, a Poundland Charles Ryder, when compared to the swashbuckling Youssef, the walking honey trap of Angelica or the captivatingly ghastly Liberty.

Had this been put out as a 200-odd page novella, I suspect I would now be saluting an instant classic, a Swiftian satire worthy of comparison with Lodge and Waugh alike, and I would expect Shibboleth to be in the running for all serious literary fiction awards over the next year. As it is, I wish that Lambert — or his editor — had had the courage to kill his darlings. Yet I suspect I know why he did not. Towards the novel’s end, Saïd says that “in all the world there’s nothing so dangerous as a bright young man, or woman, who went to Oxford and thinks it’s his job to fix it.” This novel’s author is presently a Clarendon Scholar at the university, and Shibboleth has to be seen as his crie de coeur as to Oxford’s many failings.

Much as I adored reading it — and if I come across a better first novel this year, I’ll be fortunate indeed — I cannot help feeling that the reason why Lucky Jim and Changing Places remain much-loved comic classics is that they both accept that the university, as an institution, cannot be changed in any meaningful way: it remains an ever-fixèd mark for those who spend their three of their four years studying, and will continue unaltered long after they have departed. I suspect that Lambert, in his own way, would dearly like to bring about a quiet revolution, of free thought and freer speech, but this may be too ambitious a task for any writer, let alone this hugely promising and exciting debutant.

Still, for all my carping, I cannot remember the last time that a book made me laugh as much as this, so go forth and purchase three copies: one for yourself, one for someone you love, and the last for someone you detest, so that they, too, might see the light. Who knows, they might even thank you for it.