This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

After a decade of political upheaval and assorted culture wars, it is now quite common to hear commentators lamenting the lost art of “getting along” and mourning a vanished age of polite consensus. But is divisive politics always a bad thing? Can its bracing winds actually be invigorating, or at least a necessary expression of clashes of conscience that won’t simply go away? That is one of many arresting possibilities provoked by George Owers’ vibrant study of England’s first Rage of Party.

The book throws its readers into the storms of a kingdom split down the middle over ideological questions, materialising in the form of the world’s oldest political parties. Whigs and Tories had marched into public life amidst the unstable politics of the early 1680s.

But their emergence as coherent brands really took place after the Glorious Revolution in the reigns of William III and Mary II, and then of Queen Anne, when the demands of international conflict paved the way for regular sittings of Parliament. The consequences of the 1694 Triennial Act took the country to the polls on ten occasions in 20 years, obliging statesmen to remain on a near-permanent electoral war footing.

Owers argues that the party divide gave voice to incompatibly different visions of national destiny. Whigs welcomed the legacy of the Revolution — involvement in European wars, increased European immigration and the innovations in government finance that shaped the modern City of London.

Once, Whigs had challenged Stuart monarchs; now they evolved into the party of the court and the metropolis, their sense of ease with their own age signified in the gleaming Palladian facades of their leaders’ aristocratic households.

Tories, for all their self-image as the monarch’s most faithful subjects, found themselves on the back foot, discomfitted by many of the changes seeping into the kingdom. They supported Church against Dissent, lobbied for a “blue water” focus on trade and the navy ahead of cumbersome European commitments, and spoke out for the hard-pressed country gentry, in opposition to the ever-encroaching demands of the state.

Party politics bristled with the anxieties and uncertainties of a time that brought the Act of Union with Scotland, the passing of the throne to the unfamiliar House of Hanover and the challenge posed by Jacobite princes “over the water”. Electoral campaigns served up equally savage reminders of the traumas stemming from England’s previous century of civil war, regicide and failed republican experiments.

Owers captures very deftly the impact of party competition on Parliament itself. But the book is at its riveting best when it looks beyond Westminster. Party politics, as Owers illustrates, was the engine taking debates outside the chamber into the shires, cities and provinces, and embedding national divides within cultural and religious life.

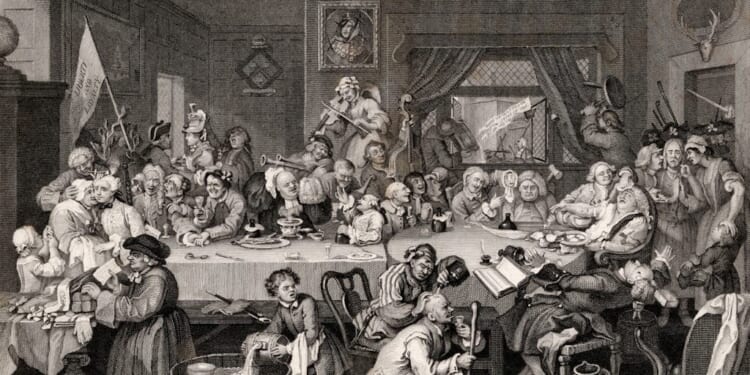

What to read, whom to employ, where to drink, what to drink — all of these choices were indented with the pressures of Whig or Tory allegiance. Electoral hustings became moments of revelry, spiced with the prospect of riot and disorder.

The party contest supplied the spirit behind the writings of Swift, Defoe, Addison and Steele, its literature enlivened by a combination of classically-honed erudition and extreme personal vitriol. It was also, as Owers argues, something of a safety valve, a form of political blood-letting that “allowed the nation to negotiate its way through a tumultuous period without another Civil War”.

But the cut and thrust of the conflict was exhausting, and imposed a physical and psychological toll on many combatants. In the 1716 Septennial Act, which drastically reduced the frequency of elections, George I’s Whig ministers took decisive action to stifle the flames.

This is an era oft-neglected, even in many universities, where it falls awkwardly between “Early Modern” and “Modern” brackets. Here it is brought back with a vengeance in a book that captures the sheer energy, creativity and scurrility of the drama. Owers concludes that the legacy of the original party split lingers today in differences of temperament and outlook, even if (some of) the issues have shifted.

His case that the nation remains riven between Whig and Tory worldviews offers, for this reviewer, a far more interesting alternative to the rather hackneyed idea of a Cavalier/Roundhead divide. It adds to the value of a work that will enthuse readers familiar with the period and captivate those who come to it anew.