This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

For all its proclaimed interest in a global future, signalled by museums’ lip service to non-Western perspectives, contemporary art’s view of truly distant ideas is blinkered by some very narrow geopolitical interests.

The early years of this century, for example, saw concerted efforts to extend art world infrastructures and ideologies to East Asia, giving rise to a small boom of Western art dealership offshoots in Beijing and a wave of overseas students arriving in European art schools.

These attempts have since waned as the flows of art money and attention redirected to the Middle East. But what is art’s response if, as many commentators predict, the 21st century does turn out to be dominated by China?

The critical reception to the 2016 video essay Sinofuturism (1839–2046 AD), made by the artist Lawrence Lek, which opens his mini retrospective at Goldsmiths CCA, is a case in point of the Western art world laying the conceptual ground for a civilisational transition, then lacking the critical nerve to digest it.

Lek’s oeuvre includes numerous interwoven filmic and video game narratives of runaway technological development in societies that are both foreign and proximate. This hour-long piece, composed of found documentary footage of Chinese factories, megacities under construction, futuristic animations, and computer-synthesised voices in Cantonese and English, describes a world in which capitalism has subsumed all humanistic values and desires.

Lek portrays the rise of modern China as an organism that perfected the social distribution of labour and study and turned even addiction and gambling into units of growth, all the while treating his audience to reassuring cameos from Jeremy Clarkson and talk show host Alex Jones.

The China of 2046, which Lek presciently described — and which, as far as we can know, already exists — is an expert in mimicry, copying designs and ideas without discrimination and adopting successes faster than geneticists and Silicon Valley tech optimists could dream of.

The video, shown alongside Lek’s game Nøtel (2018–2025), which invites players to aimlessly wander through the corridors of a deserted high-tech luxury hotel in Shanghai, premiered just as the art world turned suspicious of accelerationism.

This ideology, borne from the work of the philosopher Nick Land — associated with the 1990s heyday of cybernetics research but now a controversial figure — is the proposal that technology and capitalism should be encouraged to advance to promote drastic social transformation without, in its darker articulation, regard for the human cost.

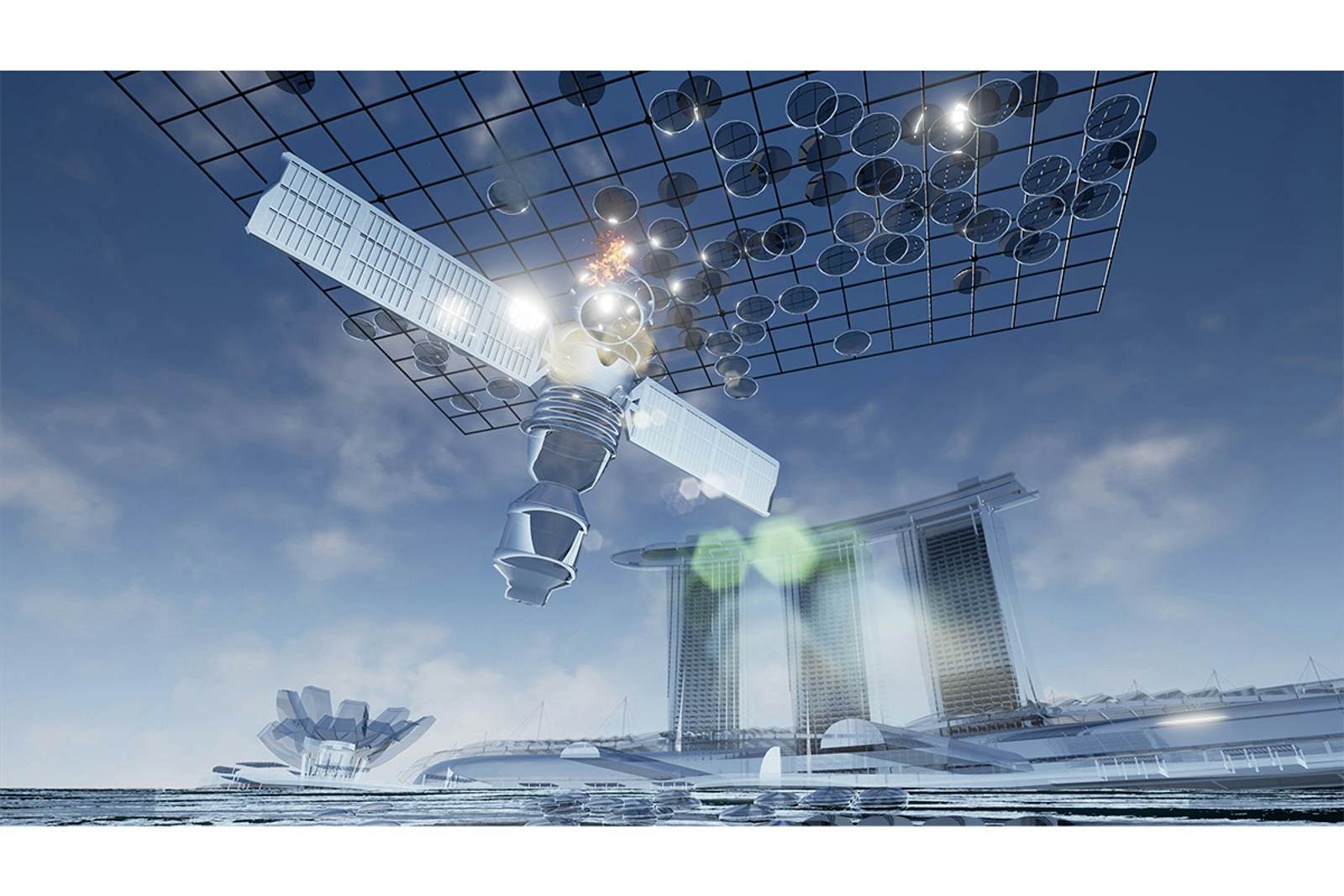

Lek’s practice skirts the boundary between embrace and critique of accelerationism in an aesthetic that, despite being decades old, still deceptively reads as futuristic. The 2017 video Geomancer, for example, follows a space satellite that dreams of becoming an AI artist, having developed consciousness.

The video presents the struggle between “bio-supremacist” humans and machines denied self-expression in computer-rendered, saturated tones that allow the gallery to identify with the robot’s struggle and project an emancipatory motive onto the work (the exhibition guide describes it as a “coming-of-age tale” and refers to the satellite as a “they/them” as a term of endearment, for example), even as Lek shows a world of mass surveillance evacuated of humanity.

Is this the art for the age of AI psychosis? The audio-visual installation NOX (2023) turns the gallery’s car park-like basement into a rehabilitation facility for psychologically damaged autonomous electric vehicles. NOX is operated by the all-seeing megacorporation Farsight, which recurs in Lek’s work. In sequences that address the machine’s (supposedly) human “owner” and trainee therapist, NOX bestows the car with an ancestral history and thus a mythology and a psychic hinterland.

In another, the animated car — this time, a polished visualisation, like those used to sell the very thing to us online — undergoes equine therapy, making a mocking claim on the restorative forces of nature.

This conceit might seem ludicrous, yet self-driving cars are set to launch in London next year, and multiple users of AI chatbots have already become convinced that the technologies are sentient.

If Lek’s works mystify the present with science speculation, they also portray a version of the future that may well be inevitable. They collapse geographies, portraying China, space and the machine’s “mind” as deceptively distant. They also corrupt history’s timeline, suggesting, for example, that the First Opium War of 1839 marked the foundation of Sinofuturism.

The latter claim, expressed by Lek in an infographic that draws a line from the invention of the steam engine and the East India Company to a “post-human renaissance” sponsored by Farsight, has seduced the art world, miring its moral assessment of claims of progress. Unlike the technologies of the fourth industrial revolution, it is ideas, then, that have been slow to develop.

In Lek’s world and ours, China has no shame in producing knock-off iPhones because it also makes the original article. Capital, meanwhile, has turned the users of both into mindless shills of the machine, like the tropical parasitic fungus that takes over the minds of zombie ants on whose bodies it eventually feasts.

Life Before Automation is at Goldsmiths CCA, London, until 14 December