This article is taken from the November 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

British nationhood was forged in the 18th century, far from its shores. It was the gift of the Royal Navy, whose military ascendency gave Great Britain unparalleled access to global trade, guaranteed her national sovereignty and allowed her to build an empire. The public grasped the idea that English liberty and Protestantism were identified with naval power over the large conscript armies massing on the continent.

In retrospect, naval supremacy looks like an obvious path for an island nation and the rewards were unimaginably greater than the difficulties and costs. Yet it was not so obvious at the time. The idea of a fully professional navy, rather than a hurriedly conscripted fleet of commercial vessels used to transport troops, involved immense expense and planning.

As warships became more advanced, the level of finance, resources and time needed to produce a powerful fleet multiplied. Entire forests had to be planted to provide ships that would see service decades in the future. It could take a lifetime to train good officers and sailors, and they, along with their costly vessels, could be lost in an instant to disease, starvation, storms and pirates, long before one considers the risks of war.

But when everything came together, the result was a miracle. Since the Jacobite rising of 1745, mainland Britain has experienced a continuous period of internal peace, protected from invasion. The Royal Navy opened the entirety of the world’s waters to commerce, even as it eliminated the global slave trade.

If naval strength could produce even a fraction of these blessings for Britain in the next two centuries, we should count it a second miracle. Yet the sad truth is that Britain is no longer a naval power of any significance.

British shipping and shipbuilding have followed the same downwards trajectory as much of our manufacturing sector. Following years of stagnation, lack of modernisation and a failed attempt at nationalisation, the government closed down numerous shipyards and privatised the most profitable builders. Yet the free market has done no better than the big state: nationalised in 1977 and privatised in 1989, after 2003 it took Harland & Wolff a full 20 years to build another ship.

Shipyard closures caused massive unemployment and coincided with the decline of the British fishing industry. European quotas and government indifference saw British fishing fleets suffer, even as European “supertrawlers” were allowed to commit ecological destruction in our waters.

Vast stretches of once-prosperous British coastline are now among the poorest regions in the country

Britain’s reversal from an industrial and seafaring nation to a country of consumers and service workers is more than just a change in economic patterns and incentives. It is a policy choice made by governments that is driving a crisis of national identity and cohesion — a crisis that is as much spiritual as material.

Vast stretches of British coastline that were once prosperous centres of trade, shipbuilding, fishing and tourism, are now amongst the poorest regions in the country. Awash with drugs, high in crime, low in employment and with ageing, unhappy populations, they are a forgotten country. This is a community abandoned by the market, abandoned by history, abandoned by its own government. Unsurprisingly these same people are declaring for Reform in droves, justly enraged by what has been allowed to happen to them.

Britain has been impotent in the face of crises it once might have meaningfully addressed. The Houthis’ ability to restrict and divert international shipping from the Red Sea and the Suez Canal, the migration crises in the English Channel and the Mediterranean, and the growing tensions with Russia and China all cry out for a strong navy. Yet despite vast expenditure, our strategic vulnerabilities are glaring.

We commission extremely advanced kit, yet don’t invest in scale, redundancy, support or supply chains. As the Chagos Islands fiasco revealed, Britain is wedded to an already outdated vision of international law to the point of self-harm. Yet that “rules-based international order” only held sway because it was underwritten by the might of armed forces — once British, now American. And American firepower, never a fully reliable ally, is under question like never before.

❂

In some ways, we are back to square one: We have lost industry, capital and expertise built up over centuries and are again a small island in a world of competing superpowers. In June, a replica of Christopher Columbus’s flagship sailed up the Thames. Anyone looking for prophetic warnings might consider themselves vindicated on hearing the recent news that a new British warship is to be built in Spain, following the acquisition of Harland & Wolff by Navantia, a Spanish company.

Yet fears that Sir Francis Drake’s handiwork is about to be undone may be premature. This time, the Spanish look to be coming in friendship. Navantia is finally doing what British shipbuilders have failed to do, and have promised to make the Belfast shipyard the most advanced in the UK, with “new lifting cranes, robotic plasma cutting systems, and automated quality control processes”.

Shipbuilding today has grown more capital intensive, technologically demanding and competitive. Building a ship, especially a warship, can take years, and companies are at the mercy of their relatively small pool of clients. Otherwise capable and well-run organisations can go bust simply because they lack the massive financial cushion needed to survive misfortunes.

Navantia, and the Spanish maritime economy is a salutary object lesson for Britain today. Spain, like Britain, is a former imperial power that has suffered badly in the wake of its fall from global influence. Yet Spain, for all its problems, has shown that one can lose an empire and gain a national purpose.

❂

I recently spent a week in Seville, a city that was once the monopoly port for Spain’s lucrative trade with its New World empire. Yet anyone imagining the shopworn glories of Portsmouth or Liverpool would be in for a surprise. Apart from its beautifully preserved historic core, it is a modern city with efficient infrastructure, glamorous shops and thriving industries. One can go to the local department store and buy local La Cartuja earthenware, made in a ceramics factory founded by an Englishman in the 19th century.

Seville is a city that has adapted. When shipping went, it built a giant tobacco factory, of Carmen fame. The same building is now a university, an important source of talent for Andalucía’s growing tech sector. Along with much of the Spanish coast, it’s a huge centre for tourism. Though the foreign hordes present their own challenges, the Spanish coastline is a very different story than the British. Spain’s marine “blue economy” was worth over €36 billion and employed nearly a million people in 2022 according to an EU report. At its pre-pandemic peak, it employed one in 20 of Spain’s working adults.

Tourism is a huge part of this picture, but one reason that the Spanish seaside is so attractive is that it is a living, working coast. Seafood caught by Spanish fishermen is served in the restaurants, good quality local goods are sold in the shops and visitors can use Spain’s extensive and efficient high speed rail network. Nor is this just surface gloss — Spain is the fastest growing major economy in Europe, and its rapidly approaching its pre-financial crisis employment levels.

Whilst British ports have declined, Spanish ports are some of the busiest in Europe, and are embracing automation. A crucial difference between our two countries is that Spain did not pursue privatisation so extensively or withdraw the state from economic intervention and investment. Its ports are state owned and managed, and Navantia is a state-owned shipbuilder.

Although private finance can achieve much, it is often unwilling or unable to commit the vast resources needed to run military shipyards, upgrade public infrastructure or manage busy ports. In areas involving basic infrastructure and strategically vital assets, the state has a clear role as the one entity that can provide the kind of stable, long term and large-scale investment needed to underpin a successful economy.

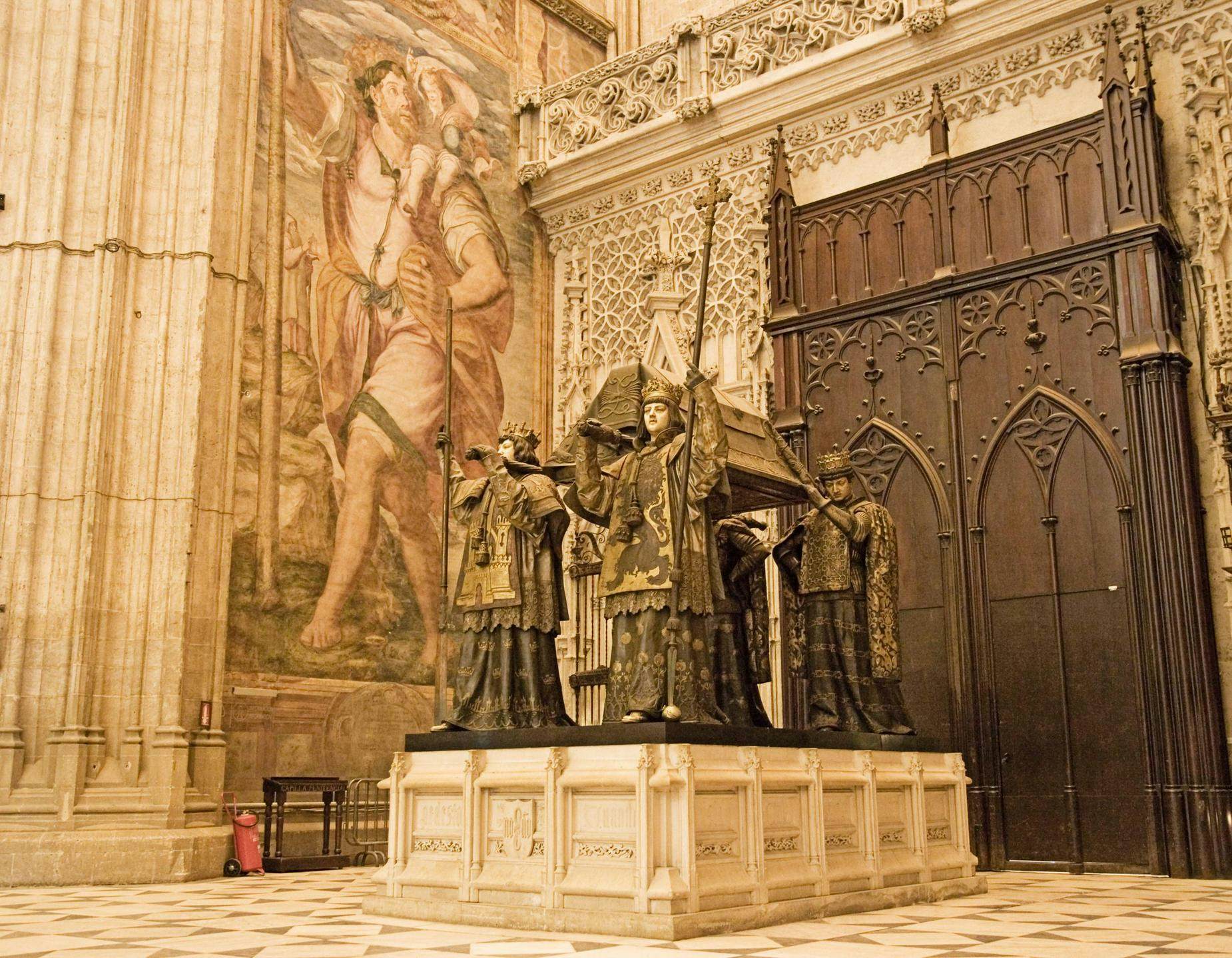

Aside from these technocratic arguments, there is a more essential political and patriotic case for the involvement of the state in the “blue economy”. Spain, like Britain, is a country whose identity is inextricably bound up with the sea. Spanish explorers discovered the New World and in the process created not only an empire, but a new Spanish-speaking civilisation. Indeed, Christopher Columbus’s tomb, rebuilt in the 19th century, looms impressively even in the gigantic expanse of Seville Cathedral, casting its shadow across history.

One can easily see how essential it is to the pride and identity of a nation like Spain that its ships still put out to sea and its coastal communities still prosper and gaze outwards. The replica of Columbus’s ship is owned by the Andalucian government, and tours the world, an instrument not only of “soft power”, but a sign of cultural self-confidence.

The British government’s boundless lack of interest in its maritime economy goes well beyond poor economic priorities or even market fundamentalism. It speaks to a deep-rooted feeling of pessimism, guilt and shame amongst the British establishment. The trauma of losing an empire, a dominant role in global manufacturing and our naval supremacy all in the span of a single generation has been too much for an elite unwilling to settle for second best and second place.

The extravagance of the HMS Queen Elizabeth and HMS Prince of Wales, £6 billion aircraft carriers still not bearing a full complement of jets, is indicative of a country averse to realistic projects proportionate to its now more modest means.

❂

Britain either spends excessively on extravagant grand projects or gives up on a thing entirely. HS2 was overengineered and overdesigned, with the result that we have taken twice as long to build something half the length it should be for many times what it should have cost. France and Spain built nationwide high speed rail networks in the time that it took Britain to build a single line.

Like a manic depressive, after the heights of overspending, we immediately revert to the slump of underinvestment. The neglect of coastal communities and industries belongs strongly to the depressive phase. Anything that isn’t a glittering success, such as our ports and dwindling fishing industry, is deemed an irrelevant sideshow. When Keir Starmer sat down with EU negotiators in May and signed away our fishing rights for another 12 years, he was indulging in a familiar and fatal prejudice.

In this neo-Whigish worldview, industries like fishing belong to the past, doomed to be supplanted by coding or public relations. But as many jobs in services and technology are being automated by AI, and as hospitality, agriculture and tourism boom worldwide (but comparatively less so here), these assumptions look dangerously naive.

In fact, the irreducible, unquantifiable and irreplaceable aspects of human life may turn out to be the most AI-proof, economically sustainable and important. What people will always desire and value will always make economic sense, and will always bring prosperity to the nation that can sustain and produce them.

Giving pride and purpose back to some of our poorest communities would restore more than a few jobs. It would recreate a lost identity, resurrect a dying culture and bring life back to the areas that most desperately need it. A visionary government would restore our hearts of oak, and steer Britain back to maritime glory.