This article is taken from the December-January 2026 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

On 15 June 2014, a long essay by Ta-Nehesi Coates appeared in the Atlantic, presenting “The Case for Reparations”. Bloomberg’s Noah Smith raised some eyebrows last year for naming Coates as one of the five most important people of the 2010s. Reading “The Case for Reparations” today, one begins to see Smith’s point: it’s like that apocryphal lady who, watching Hamlet for the first time, complained “I don’t see why people admire that play so — it is nothing but a bunch of quotations strung together”.

All the ideas of 2020 are there, in embryo: America was founded on exploitation and brutality; the Civil War was fruitless, because slavery persisted under other guises; this explains all racial disparities today. Just as familiar to the post-Floydian reader is Coates’s cloying, therapeutic demeanour. “Reparations,” he says, “beckon us to reject the intoxication of hubris and see America as it is — the work of fallible humans.” What the cost of this would be to the American taxpayer was left cautiously unstated. No doubt it is substantial.

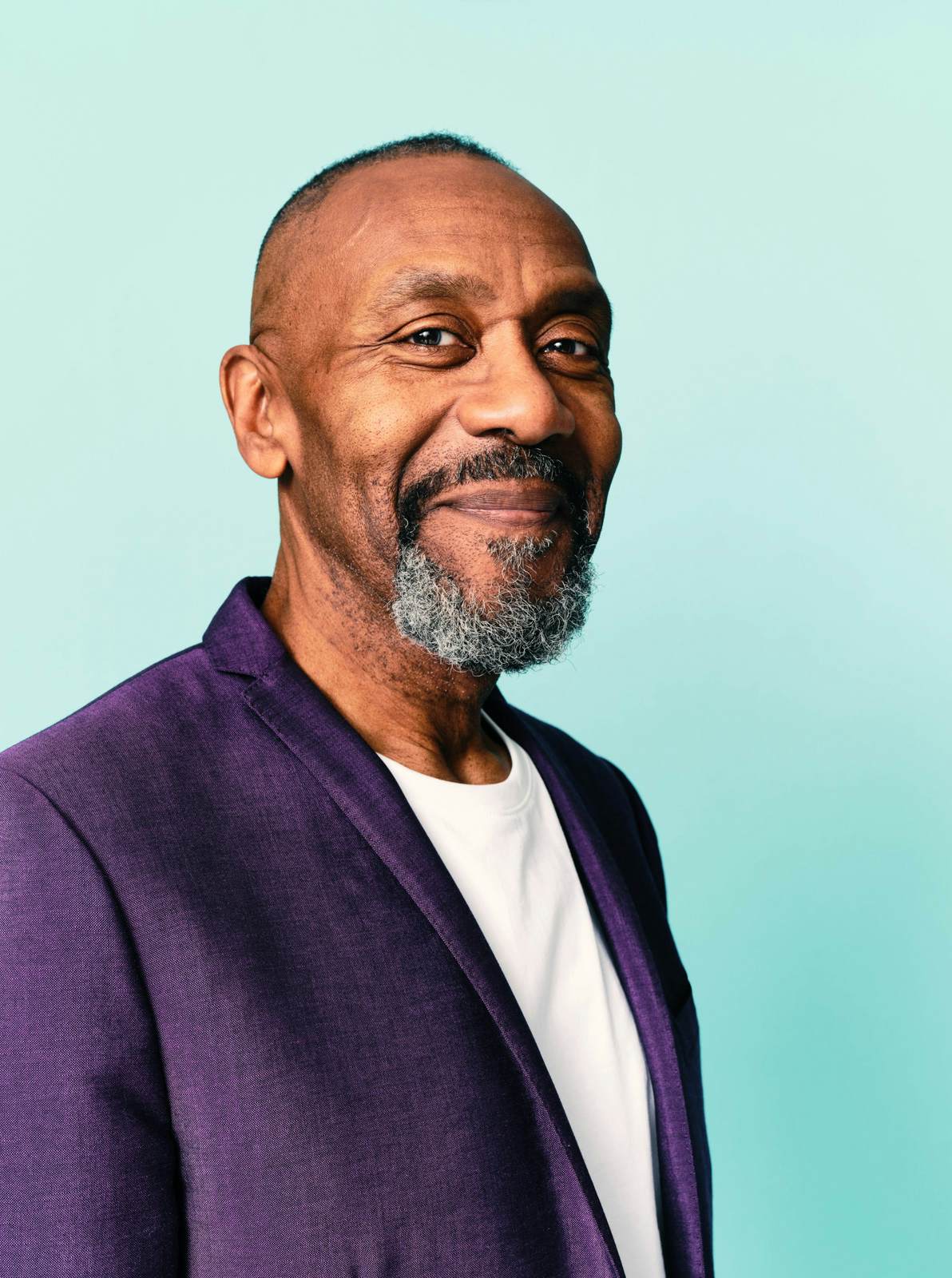

Sir Lenny Henry has a number: 18.62 trillion pounds. “That’s it,” he says in The Big Payback, his effort to repackage Coates’s arguments for Britain: “Mind blown. POW!!!” He wants it in pound coins, so he can “swim in it like Scrooge McDuck”. At 70 per cent packing efficiency, that would require about 13,000 Olympic pools. In fact, 18.62 trillion pounds is a lower bound: that’s just the sum owed to the Caribbean, but black people in Britain, Henry argues, deserve reparations too.

Henry summons an army of professional activists to make the case with him. There’s Cleo Lake, a Bristol “community leader”, who launched the Global Afrikan People’s Parliament in conjunction with the “maatubuntujamaa Afrikan Heritage Community for National Self-Determination” (me neither).

There’s Professor Kehinde Andrews, who charms Henry with his “smoother-than-a-cat-wearing-a-velvet-tuxedo manner” (Andrews says the British Empire was “far worse than the Nazis” and calls black people who disagree with him “house negroes”, guilty of “cooning”). Another talking head is billed as “the kind of guy who can spit lyrics on T’Challa and bell hooks simultaneously, bruv, y’get me?” I must confess I do not.

For a book written by one of Britain’s most successful comedians, The Big Payback is unfathomably unfunny. Henry jumps up and down like a class clown, desperate not to lose his audience’s attention. He starts by riffing on the potential double-meaning of “Black Country”.

He thinks it is hilarious to imagine that the Trinidadian statesman and scholar Eric Williams had written a book called “The Very Hungry Capitalist”. He winkingly nicknames his racist school bully “Nigel”, the page after “definitely not saying Farage and followers are a racist party”.

For reasons unclear, he devotes two whole pages to his recipe for Jamaican Saturday soup. There is precisely one passable joke, of the “so bad it’s good” variety. So many calls for reparations, Henry complains, are met with “Yes, but … ”; and, channelling Sir Mix-A-Lot, he quips “I like ‘Yes But’ and I cannot lie”.

As for the book’s actual arguments, there is only the detumescence of flashy claims and flimsy evidence. A section under the heading “Slavery gave us the monarchy” turns out to be about how James II was spared some financial trouble by the help of the Royal African Company (how did things turn out for him?). On matters of detail, Henry passes the buck over to his co-author, Marcus Ryder, with a plea for the reader to “bear with”.

Despite Henry’s insistence to the contrary — “Wow, that was deep”, he says lamely after one of Ryder’s interjections, “like if the Mariana Trench has a basement” — Ryder, formerly of the Sir Lenny Henry Centre for Media Diversity, does not seem fit for the task. We take our history lessons from someone who refers twice, in a digression on Zionism, to something called “the Balfour Agreement of 1948” which “established the State of Israel”. It is a revealing error: presumably Ryder thinks that Israel, and all the problems that went along with it, were called into being directly by British colonial fiat. Does Ryder know that Britain was neutral on Israeli statehood in 1947 and armed the Arabs in 1948? You can bet the farm he doesn’t.

The Iraqi Jew Elie Kedourie once argued that Britain’s policy in 1948 was motivated by the “canker of imaginary guilt” over the supposed betrayal of the Arabs in the Balfour Declaration of 1917. Nigel, Lord Biggar is fond of this line, finding its echoes reverberating today: he deployed it in his Colonialism: A Moral Reckoning, and it appears again now in Reparations: Slavery and the Tyranny of Imaginary Guilt.

The point is that excessive self-flagellation over colonialism and slavery can have serious negative effects. When Canada pressed China over its treatment of the Uyghurs, for example, President Xi could easily retort that Canada was, on its own absurd admission, concurrently committing a genocide of its own against its indigenous population.

It may seem unfair to set Oxford’s Emeritus Regius Professor of Moral Theology against a comedian best known for Tiswas and Red Nose Day. Still, moving from Henry’s incoherent ramblings and smarmy banter to Biggar’s book is like escaping a tar pit for the open savannah. Each chapter opens with a clear argument and supports it with a chain of well-evidenced premises.

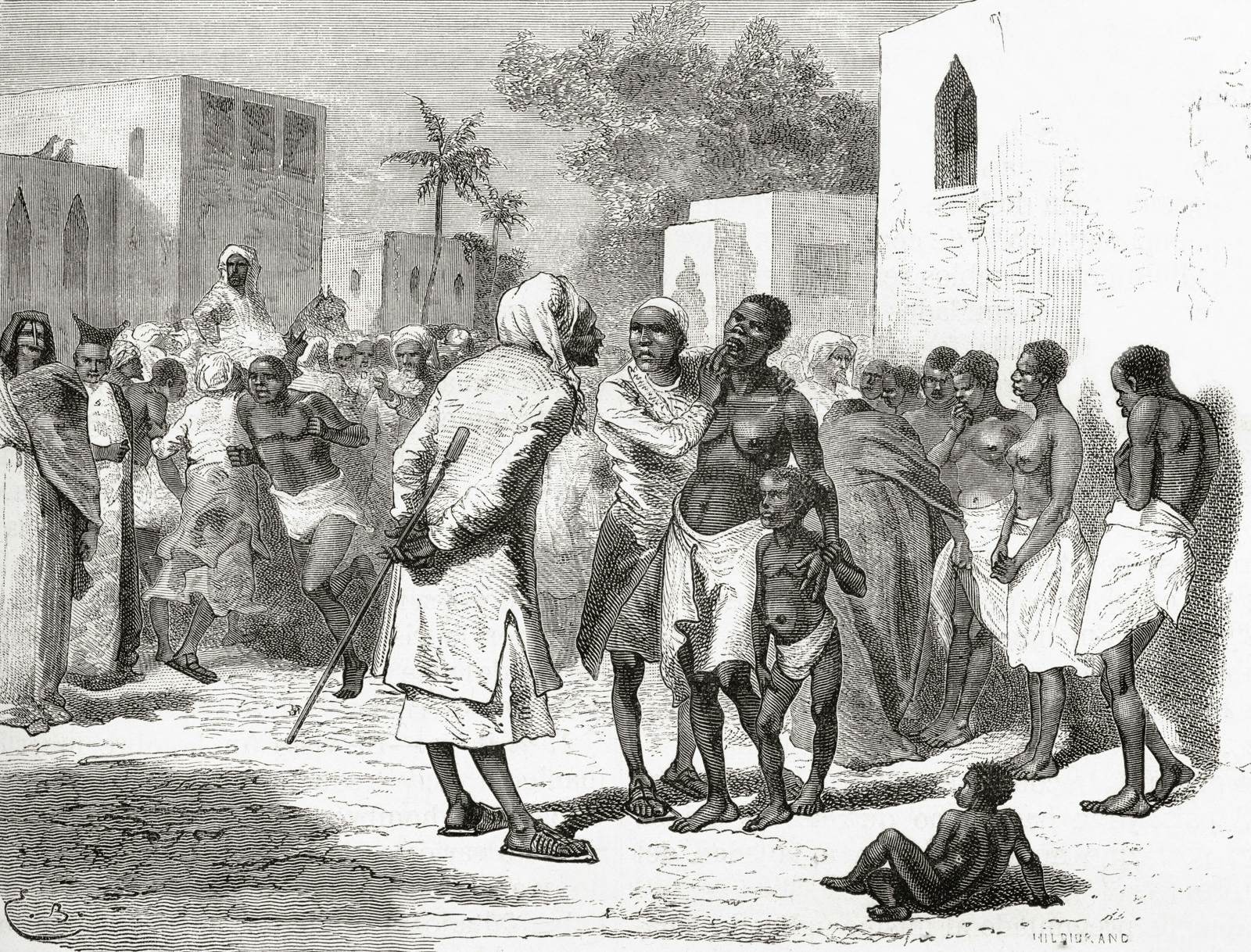

Biggar accuses the supporters of slavery reparations of making no effort to reckon with the fact that slavery was a historic universal, and taking no account of the British Empire’s strenuous and unprecedented efforts to abolish the practice.

Above all, he underscores the impossibility of drawing tidy links between the world 250 years ago and the world today: “The riotous jungle of history overgrows and obscures the causal pathways.” There is in Biggar’s book no whitewashing of the past: in fact, there is more of the actual horror of slavery here than from The Big Payback. Whereas Henry and Ryder gesture vaguely at various “traumas” suffered by black people in Britain today, with Biggar we get the appalling realities of the triangle trade direct from Olaudah Equiano’s quill.

The Big Payback ends with a draft of a play which Henry has written and intends to put on. The plot is straightforward. A white celebrity finds out on a “Who Do You Think You Are”-style TV show that he’s related to a black family in Birmingham, “because of what your forefathers did to the slave women”.

He goes to meet them, eats their Saturday soup and nervously offers them reparations — but it turns out that he has committed a faux pas. “I AM NOT YOUR FUCKIN’ VICTIM!” screams one of the black characters. The scene ends with the celebrity curled up in a ball, crying and saying sorry.

It is tempting to look at Henry’s play as an admission that the whole thing is really an exercise in humiliation and domination. It is tempting to pick up Biggar’s book, likewise, and say that the moral case for reparations has now been conclusively rebutted.

Still, we shouldn’t be complacent: we must recognise what is at stake. Henry is a multi-millionaire who recently starred in The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power, the most expensive TV show of all time. Now he is calling to squeeze Britain for pennies until the pips squeak. This all could be laughed off; but, as the Chagos debacle has proved, the “canker of imaginary guilt” continues to afflict the Foreign Office, and a number of Labour MPs are supportive of Henry’s efforts.

No, no, Henry and Ryder insist, we don’t want poor people to pay reparations; “the question is whether the current British government is responsible for crimes committed by successive British governments years ago”. Well, if the current British government were somehow to cough up 18.62 trillion pounds or more, who do they think would end up footing the bill? And would it really serve the interests of black Britons for their country to become substantially poorer?

In all this there is a certain sadness. Henry was once the poster-boy for a cohesive multiracial Britain. “Enoch Powell says he wants to give me £1,000 to go back to where I came from,” goes one of his most famous jokes, “which is great, because it’s only 20p on the bus from here to Dudley.” Now he wants to immiserate his own countrymen.

At one point he says that it would be fine for Britain to pay reparations directly to Jamaica, because he has a claim to Jamaican citizenship anyway: well, it must be said, Jamaica is more than a 20p bus-ride away. It’s hard to shake off the feeling that an older, patriotic multiculturalism has curdled in recent years into something different, something worse. That, more than anything, leaves a sour taste in the soup.