This article is taken from the October 2025 issue of The Critic. To get the full magazine why not subscribe? Get five issues for just £25.

The year was 2020, and a group of activists were campaigning to rename a street. It was “disgusting”, declared one, that it should bear the name of a slave trader. “We demand a change,” said another, demanding an apology to boot.

Such “reckonings” were all the rage in Britain around this time: no more Colston Street in Bristol; even the Beatles’s very own Penny Lane wasn’t safe. But this drama was playing out 5,000 miles away. The city was Khartoum, and the street in question bore the name of the 19th century warlord Zubayr Pasha. The street kept its name, and no apology was forthcoming.

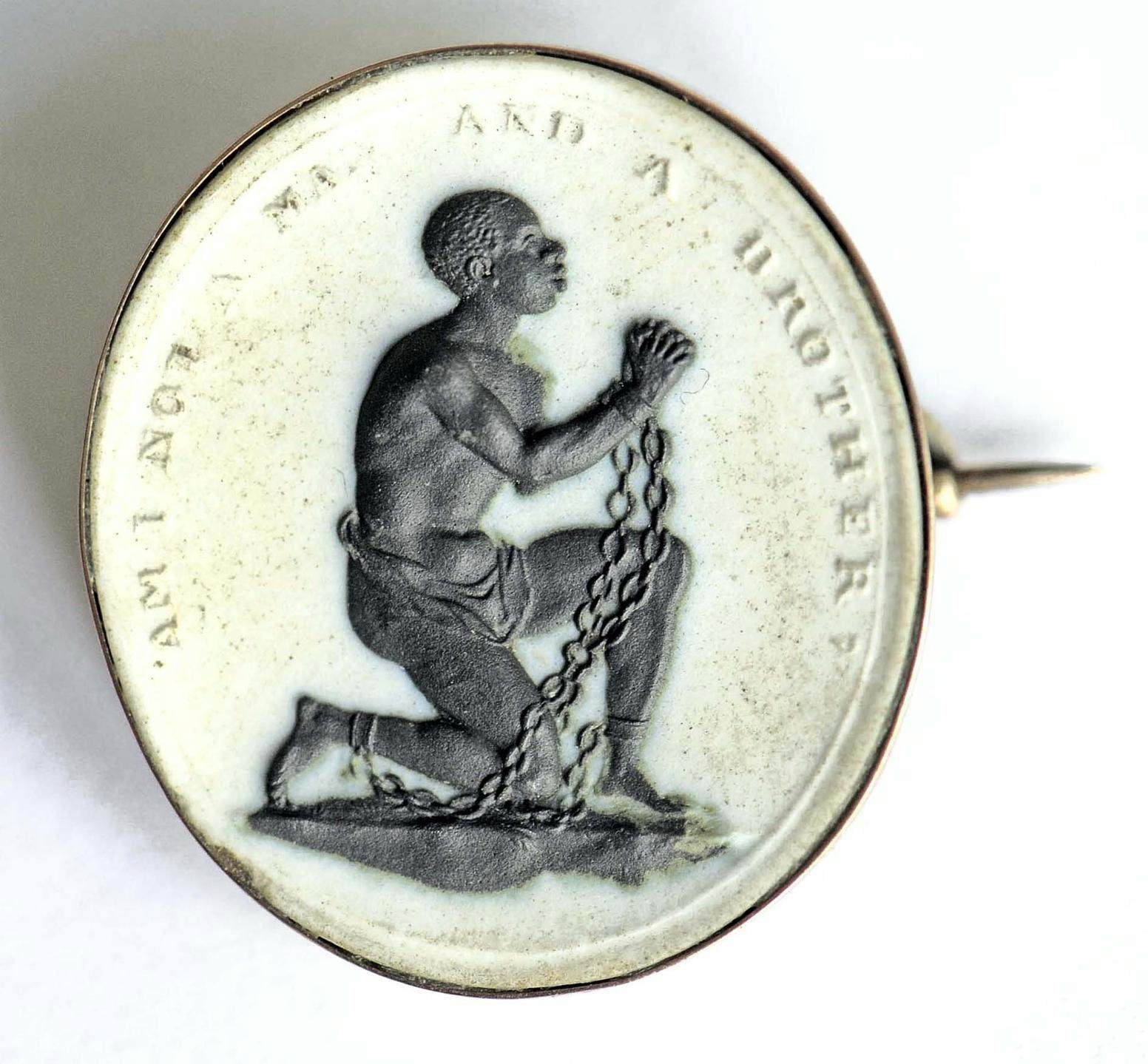

If we are not accustomed to thinking about the legacies of slavery in Africa and the Middle East, it is because our received history of slavery is confined to the Atlantic. James Walvin’s Short History of Slavery (2007) devoted 201 of 235 pages to the Americas: the famous Wedgwood anti-slavery medallion, “Am I not a man and a brother?”, appears on its front cover.

This lends credence to James Hunwick’s estimation that “For every gallon of ink that has been spilt on the transatlantic slave trade and its consequences, only one very small drop has been spilt on … the broader question of slavery within Muslim societies.”

As one recent study of the 19th century slave Fezzeh Khanom puts it, “The history of slavery in Iran has yet to be written.” A general history of slavery in the wider Islamic world had yet to be written, too — until Justin Marozzi took up the task.

The widespread neglect of the history of slavery in North Africa and the Middle East, which Captives and Companions seeks to redress, partly reflects a culture of American exceptionalism; slavery in other parts of the Americas (it was abolished in Brazil only in 1888) also receives little attention.

Partly, too, it reflects a tradition of denial in the Islamic world itself. Marozzi recalls a professor at Bilkent University in Turkey admonishing a younger historian not to dig too deep: “Our ancestors treated their slaves very well; don’t waste your time.”

In the West, meanwhile, Islamic slavery is an unfashionable — and often suspect — subject: one is reminded of West Germany in the 1980s, when any overemphasis on Soviet crimes against humanity could appear as an attempt to whitewash or relativise the Holocaust. Marozzi is careful not to dwell too much on comparisons between Islamic and Atlantic slavery, except as regards the scholarly attention which they have received. Still, many readers will pick up his book hungry for such comparisons. So here they are.

In both Islamic and Atlantic slavery there was a marked racial — anti-black — component. Slavery was sustained by similar religious and philosophical justifications: the biblical “curse of Ham”, for example, and the idea that geography and climate made sub-Saharan Africans naturally suited for servitude. “Chattel slavery”, Marozzi emphasises, existed in the Islamic world too. Both involved horrific violence and displacement. Both were complex and sophisticated enterprises, often with serious money at stake.

People have always been hesitant to draw any comparisons between Islamic and Atlantic slavery, albeit often for entirely opposite reasons to historians today. Whereas the Jewish-American writer Mordecai Manuel Noah was a vocal supporter of the enslavement of Africans in America, he was also bitterly opposed to the enslavement of Americans in North Africa — and therefore a strong supporter of America’s involvement in the Barbary wars.

Gladstone, meanwhile, thought that Turks killing and enslaving Europeans was far worse than “negro slavery”, which had at least involved “a race of higher capacities ruling over a race of lower capacities”. However dubious his family connections, Gladstone was born after Britain had abolished the slave trade.

The lack of attention given to Islamic slavery is all the more dismaying when one considers just how much longer it survived.

Most of slavery’s 20th century holdouts were in the Islamic world. Iran abolished slavery in 1928; Yemen and Saudi Arabia in 1962; Turkey — which we like to consider more “Western” than the others — in 1964. Mauritania half-heartedly abolished slavery in 1981. Slavery was still a feature of elite life in Zanzibar as late as 1970. When 64-year-old President Karume took an underage Asian concubine, he justified it by declaring that “in colonial times the Arabs took African concubines … now the shoe is on the other foot”.

The Royal Harem in Morocco, meanwhile, was only dissolved on the death of Hassan II in 1999. In the Islamic world, human beings were bought and sold, and forced to do demeaning and painstaking labour, within living memory; some people languish there still.

The key difference between Atlantic and Islamic slavery concerned status. Slaves in the Islamic world could rise to high places: 35 of the 37 Abbasid caliphs were born to enslaved concubine mothers; the slave eunuch Abu al Misk Kafur was regent over Egypt from 946 to 968. Slave dynasties, most notably the Mamluks, were amongst the most powerful in the Islamic world.

The polyglot governor of Hong Kong, Sir John Bowring, when he inveighed against “slavery in the Mohamedan states”, had no choice but to acknowledge that a slave in the East could attain the “highest social elevation” — a far cry from the black slaves of the West Indies. Some slaves, too, were amongst the worthies of Islam, such as the first Muslim martyr, Sumayya bint Khabat.

Slavery occupied a complex place in Islamic law. The Quran, on the one hand, permits men to have sex with female slaves. But on the other, the emancipation of slaves is smiled upon as one of the noblest things a Muslim can do. The Abyssinian slave Bilal ibn Rabah was freed by Abu Bakr and became the first caller to prayer; another freed slave, Zayd ibn Haritha, was briefly the Prophet’s adopted son.

The Quran also expressly forbids Muslims from enslaving fellow Muslims. Nonetheless, as Marozzi shows, this prohibition has not always been strictly observed. The Mahdi (of General Gordon fame) claimed to represent pure, Islamic orthodoxy, but he had no qualms about enslaving Muslim Turks.

Likewise, it mattered little that the Prophet Muhammad had explicitly forbidden castration of male slaves. For over a millennium his tomb in Medina was guarded by a corps of eunuchs. This, too, was an institution which survived into living memory: in 2022 a Saudi newspaper reported that there remained one living eunuch guardian.

Islamic slavery, much like Atlantic slavery, cannot be understood without considering anti-black racism. Prejudice towards black Africans pre-dated the rise of Islam. The 6th century pagan Arab poet, Antara ibn Shaddad, wrote how “Fools may mock my blackness”. The motif endured: “Blackness does not diminish me, as long / As I have this tongue and this stout heart,” wrote Nusayb ibn Rabah in the early 8th century.

The brutal subjugation of black slaves in the Abbasid caliphate led to the Zanj Revolt, one of the most dramatic events in Islamic history. It is an enthralling episode, and Marozzi’s page-turning narrative will hopefully make it better known to Anglophone audiences.

Marozzi does more than simply narrate past events. He takes the story up to the present. He begins the book interviewing an escaped slave from western Mali, whose recollections underscore that slavery now is no less cruel and sadistic than it was in the Middle Ages; the man’s former master often exercised the equivalent of medieval Europe’s droit du seigneur.

Marozzi has also seen first-hand the legal case being prepared by the Commission for International Justice and Accountability against ISIS, which made the enslavement of Yazidis “official policy” and justified the rape of enslaved Yazidi women by quoting Islamic law.

The book closes with Marozzi visiting the 21st century’s worst centre of slavery, Mauritania. This is not a country that encroaches much upon the Western mind, and the Mauritanian government clearly likes it that way. Marozzi describes being interrogated by Mauritanian police officers, followed by security officials, and monitored by informants.

Because Marozzi’s writing is crystal clear, the book can make for difficult reading. There is no jargon or innuendo: Captives and Companions drives home man’s cruelty to man in graphic detail. Slavery was a true historic universal, and it exists today in countries such as Mauritania in a manner which strikes us as appallingly anachronistic and which we might therefore prefer to put out of mind.

Whilst the book offers few glimpses of redemption, there are some poignant moments. One comes when he describes a slab of limestone in the Holy Land, commemorating an unnamed slave girl who belonged to the grandson of the 9th century Abbasid caliph al-Ma’mun. That slab is all the poor woman got. But now she and others like her get this book, which brims with empathy for those who tend to get none.