Strapped into a crude homemade straitjacket and tied to a child’s potty, Genie Wiley knew nothing outside the darkness of her sparsely furnished bedroom until she turned thirteen.

Despite living with her parents and older siblings, Genie didn’t know love, affection, or joy; the only toys she had were empty margarine pots, magazines with the colourful pictures torn out and empty thread spools.

It is alleged that when Genie was around 20 months old, a paedeatrician told her parents that she was showing signs of being mentally disabled.

Her father, Clark, banned her mother, Irene, who was partially sighted and had mental health issues, from interacting with her, and locked her away in her dank bedroom day after day, placing her in a makeshift cage overnight.

There were no sounds in the Wiley house. Her mother and older brother were forced to communicate in hushed tones and whispers, there were no voices from a television or radio set, and no music.

Genie didn’t know how to communicate—from infancy, every time she made a sound Clarke would bark at her like a vicious dog or hit her, scaring her into silence.

For over ten years, he was the only member of the family who interacted with her, but there was no gentleness.

Clark oversaw her meals, feeding her a watery gruel made of milk and rice cereal, with the occasional boiled egg. Because of her limited diet, she suffered from chronic malnutrition, and had never learnt how to feed herself.

Genie Wiley was categorised as a ‘feral child’ because of the developmental milestones she missed because of her abusive childhood

Furthermore, the lack of nutrients stunted her physical growth and further stifled her mental development. She was so tightly bound to her potty that she was only able to move her hands, fingers, feet and toes.

Because of the abhorrent way she was treated, Genie missed every major psychological milestone, only understanding twenty words by the time she reached adolescence.

Her limited vocabulary mainly consisted of negative or aggressive words, including ‘stopit’, ‘nomore’, and ‘no’.

Genie’s devastating story became public knowledge after her rescue in November 1970. It left the American public appalled—but the psychiatry and linguistics communities were ablaze with excitement.

Genie had essentially been raised in isolation, away from human society and normal developmental experiences, placing her in the category of a ‘feral child’.

The frail and non-verbal teenage girl presented scientists and researchers with an incredibly rare opportunity to explore what happens to the human brain when it is not exposed to external stimulation.

Studying Genie would allow them to explore the Critical Period Hypothesis (CPH), a theory which argues that there is a specific time in human development—from childhood to puberty—where the brain is best equipped for learning a first language.

For ethical reasons, it’s impossible to test this theory on living subjects, but with Genie, they had the opportunity to see if a child could learn a language once the hypothetical window had closed.

Genie captivated everyone who met her, but she became a pawn in a scientific tug of war

Was it too late to teach her how to communicate, and one day hear her story in her own words?

Psychologists were also excited: What primitive behaviours, usually overwritten by societal norms, would she demonstrate? Could she be the key to unlocking the mysteries of nature versus nurture?

But the waif-like child didn’t just spark interest amongst the scholars who saw her as a subject to be studied; well-natured people who wanted to give her the love and affection she had never known clamoured to take her in and care for her. A tug of war erupted around her.

Genie’s early life had been a genuine real life horror story, but tragically for the vulnerable young woman, her tale doesn’t have a happy ending.

The second half of Genie’s life began in November 1970, when her mother took her to the offices of the Los Angeles County Welfare Office in Temple City, California.

However, it wasn’t a crisis of conscience which had led her there—she wasn’t seeking help for her daughter, but for herself.

Genie’s mother was blind in one eye and had just 10 per cent vision in the other due to cataracts, and was hoping to find out what support was available to her.

Unable to navigate her way around the building’s maze-like layout, she accidentally stepped into the offices for general social services, where her daughter’s unusual gait and behaviour immediately caught the attention of staff.

They believed Genie was no more than six or seven years old, and likely severely autistic, noting she had a stooped posture and strange, shuffling gait.

The girl drooled and spat, and held her arms in front of her with her wrists flexed, in a ‘bunny hands’ position. Assessments revealed that she had the language level of a one-year-old.

Eyewitness reports at the time described her as a ‘small withered girl [with] a halting gait [and] hands held up as though resting on an invisible rail.’

A supervisor was immediately alerted, beginning a chain of events that transformed the young girl’s life.

Child services sprang into action and after visiting the Wiley family home, removed Genie, and finally gave her brother John, who was five years older, a chance to escape his domineering father’s clutches.

What the Wiley family had endured at the hands of Clark soon became public knowledge; sickening stories of mental and physical abuse, a family forced to live and move in complete silence and unable to escape the domineering patriarch who slept by the front door with a shotgun on his lap.

Allegedly, Genie had been locked away by her father to protect her from the horrors of the outside world.

For 11 years, her days were spent harnessed naked to a toddler’s potty so she wouldn’t soil on the floor, locked in her bedroom with no natural light and not even the sound of a radio to keep her company.

Because she spent her childhood in a straitjacket, Genie walked with a ‘shuffled gait and arms held out like a bunny rabbit’

At night, with her arms restrained, she slept inside a zipped up sleeping bag locked inside a ‘crib-cage’ her father had fashioned out of wire and wood.

Her bedroom walls were bare, she had none of the traditional trappings of childhood, no cuddly toys, no dolls, no books; no colour nor softness.

Clark’s ultimate motives for how he treated his daughter, wife and son were never known. He died by a self-inflicted shotgun blast on the day he was due in court on child abuse charges.

His suicide note simply read: ‘The world will never understand.’

Irene, however, did not escape her day in court, and pled not guilty on the grounds that she had been forced to act the way she did by her abusive husband.

Her plea was accepted, and Irene agreed for Genie to become a ward of the state.

For the following five years, she was under the intense care of specialists at the Children’s Hospital at UCLA, spending time both on the wards and the staff’s homes.

One of the experts who worked with her, linguist Dr Susan Curtiss, explained that Genie was a pseudonym given to the young girl to protect her identity.

Speaking in a 1997 documentary called Secrets of the Wild Child, she said the name was chosen to reflect her sudden appearance into the world.

‘The case name is Genie,’ she said.

‘This is not the person’s real name, but when we think about what a genie is, a genie is a creature that comes out of a bottle or whatever but emerges into human society past childhood.

‘We assume that it really isn’t a creature that had a human childhood.’

Curtiss was a constant presence throughout Genie’s recovery, penning a book, Genie: A Psycholinguistic Study of a Modern-Day Wild Child, in 1977 about her experiences and observations.

Speaking to ABC News, Curtiss said: ‘I was a very young woman given the chance of a lifetime.

‘[Genie] wasn’t socialised, and her behaviour was distasteful, but she just captivated us with her beauty.’

Curtiss noted that at the end of her treatment, Genie had developed some ability to use words and had expanded her vocabulary, but she was unable to grasp the concept of or use grammar, adding more weight to the Critical Period Hypothesis.

For instance, when speaking about her abusive childhood, she would say: ‘Father Hit Arm. Big Wood. Genie Cry.’

Researchers were also never able to fully determine if Genie had any pre-existing cognitive deficits which would have affected how she learnt language as a child, if her situation was down to the conditions she experienced in her formative years, or a mixture of the two.

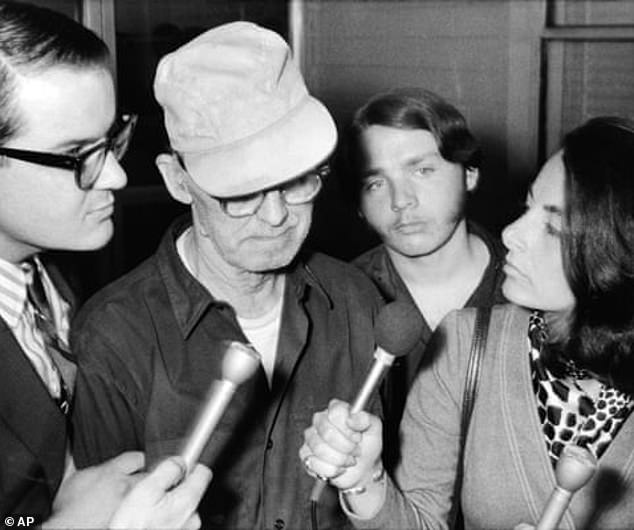

Genie’s father Clark Wiley, 70, shot himself on the day he was due in court on child abuse charges

Immediately after being removed from the Wiley home, Genie lived in specialist accommodation at the UCLA Children’s Hospital where she began rehabilitation therapy.

After a short time, to avoid a measles outbreak at the hospital, she moved into the home of Jeanne Butler, one of the hospital’s rehabilitation therapists, and the new environment reportedly increased her progression.

Genie quickly learnt how to do basic activities, such as use the toilet and dress herself, and she reportedly enjoyed being taken on excursions, and would appear delighted by new sights and sounds.

But when Butler asked to become her foster parent, the Department of Public Social Services denied the request, citing a hospital policy that prohibited placement of patients in the homes of employees.

Frustratingly for Butler, Genie was instead placed in the care of Dr. David Rigler, a colleague from the Children’s Hospital, and his wife, Marilyn, where she stayed for the next four years.

Butler argued that Genie had been taken from her because she was focused on giving the vulnerable teen a warm and happy home life which was keeping her away from the researchers, who she believed were acting exploitatively.

On the other hand, the researchers accused Butler of wanting to use Genie for personal gain and fame.

Although Genie’s ability to communicate was limited, everyone who worked with her commented that she had a magnetic presence which drew people in.

Dr Rigler said: ‘I think everybody who came in contact with her was attracted to her.

‘She had a quality of somehow connecting with people, which developed more and more but was present, really, from the start.

‘She had a way of reaching out without saying anything, but just somehow by the kind of look in her eyes, and people wanted to do things for her.’

Sadly for Genie, she faced more upheaval in 1975 after the US National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) removed funding for Dr Rigler’s research project, ‘Developmental Consequence of Extreme Social Isolation’.

Genie was returned to the care of her birth mother, who had regained some of her vision after cataract surgery, but Irene was unable to cope with her now 18-year-old daughter’s incredibly complex needs.

Genie was sent to live in a series of foster homes, none of whom were able to offer her the care and consistency she had experienced from either the Riglers or Butler. She was allegedly subjected to abuse at the hands of her new caregivers, including being punished for vomiting, and she rapidly regressed.

When Genie was returned to Children’s Hospital, she had lost the ability to communicate in any form, and was entirely mute.

By this time an adult, she was institutionalised by the state, with few details ever shared about either her whereabouts or her condition.

Psychiatrist Jay Shurley claimed to have visited her on her 27th and 29th birthdays and described her as being ‘largely silent, depressed, and chronically institutionalised’.

It is not known if Genie is still alive today, but if she is, it is presumed she remains a ward of the state of California, and will be living out her days in an adult care home.

Just like at the start of her life, she will be languishing in an invisible cage of silence; but now, she will be around 67 years old.